Ep. 127: Artist & Designer Bethan Laura Wood

Artist and product designer Bethan Laura Wood grew up with ample access to kitchen-table craft projects and a flair for self-expression. When kids made fun of her clothes, she reclaimed her style by going full-on “dress-uppy.” Her schooling, which included a craft-based technical track as well as conceptual rigor, has armed her with a finesse for elevating industrial materials to luxury levels, layered with depth and intrigue. Side note: she is known to travel in style, much to the delight of TSA agents!

Read the full transcript here.

Bethan Laura Wood: A lot of my work is very layers based, both visually and hopefully theoretically. I describe it as distance through detail.

Amy Devers: Hi everyone, I’m Amy Devers and this is Clever. Today I’m talking to Bethan Lauren Woods. She’s a London-based artist and product designer at the head of her namesake multidisciplinary studio characterized by materials investigation, artist collaboration and passion for color and detail. Her work spans furniture, lighting, fashion accessories and window displays. She earned an MA in design products from the royal college of art, has exhibited in museums and galleries internationally, has collaborated with brand partners such as Hermes, Abet Laminati, Moroso, Tory Burch, and more. And she’s a charming and colorful character to boot. Take it away, Bethan Laura Wood.

BLW: I’m Bethan Laura Woods and I am currently in London and I do lots of different things, but predominantly I work within the design sector and I make stuff.

AD: [Laughs] So, can we dial it all the way back to young Bethan Laura? I wanna know what your childhood was like. You have such a colorful persona as an adult; I’m imagining the childhood may have been colorful too. So will you tell us all about your home town and family dynamic and the things you were fascinated in?

BLW: Sure. I think like the 90s is more, there was kind of a big cybergoth of a look going on or I was too colorful to be an actual Goth, which was more the movement going on in my hometown. So yeah, I’ve been quite dress-uppy for a while. I’m from a small town in the Midlands called Shrewsbury and that’s kind of, yeah, central, middle England, not that far from Wales, is kind of how I describe it.

And I lived with my mum and my father and my sister and both my parents are quite creative in their own ways. So my mum would do a lot of sewing of everything. We would make stuff all the time with her and my father is an architect, but he specializes in healthcare and hospitals. So it’s a very different narrative of architecture that he does to the kind of design fields that I’m in. But I think it’s kind of quite amazing how focused the type of architecture he does to obviously make things work for a very particular function.

But it’s obviously quite different to the colorful things that I do. Yeah, that’s kind of my family and hometown.

AD: So surely that made an impression on you, your young psyche. Did you have a sense of what your dad was doing for work and the practical parameters of it?

BLW: I’m, I was very aware that my dad would point out faults in the architecture of many like restaurants we’d go into in relation to health and safety or not being rhythmically even in the way that they placed the lights and things like that. So I definitely started to pick up on some dos and don’ts in the rhythms that my dad finds correct or aesthetically pleasing in interiors. So yeah, little bits and bobs, but he’s not a super-super chatty guy. So I’ve enjoyed learning nibbles to do with what he does, every once in a while I’ll get another nugget.

Though I don’t work in that sector, I think this kind of very strong kind of obsessional attention to detail is something that I hope that I carry over well into like my genre of work. I think that’s kind of how bits of my dad’s kind of work filtered through me as a child. But a lot came from my mum and sewing and sticky back plastic and toilet rolls and paper-mache. If I could make it on a kitchen table, I probably did during my childhood.

AD: That sounds so fun! So as you progressed into adolescence, how were you expressing your creativity and when did the dress-uppy chapter start

BLW: I don’t know what grade it’ll be in, for you, but it’s Year 8, I think when you’re about 13 or 14 maybe. I kind of more consciously decided at that point, if I was gonna have the mickey taken out of me, then I might as well go all the way. If they’re not nice to you about how you like normally dressed, then you might as well take it full throttle to your own advantage and freak them out rather than kind of go backwards.

AD: So the fact of reclamation, I love this.

BLW: Thanks, yeah, I mean I don’t think, the teachers didn’t quite see it in that direction. I do remember being told to wash makeup off my face when I did dot-dash lines with an eyeliner pencil, put contours on my face and I was told that’s not appropriate and I kind of tried to defend the fact that I probably had less makeup on than some of the other students. But that didn’t, you know, I just had it in different places to where they put it. But that didn’t work and I was made to wash it off, so.

AD: Oh frustrating authoritarian conformist ideals [laughs].

BLW: It’s a weird one with school isn’t it that it’s kind of like this kind of conformity of, I do understand why the like, the nice side of the idea of everybody having a uniform and how that can give you a sense of identity and this kind of thing, but it also can kind of reinforce an idea of one particular way of being, being the correct way and no other way can also be acceptable. So yeah, I did rebel in my own small ways at school to try and find alternative routes to clothing.

You were allowed to sew your own summer dresses, which I think is kind of amazing that they still, your parents would still sew your summer pinafores at that time. So my mum did and she made me a giant doll dress and she sewed me a few variants on the theme of and more unusual cut, let’s put it, but it was in the correct fabric and it was at the correct length so they couldn’t stop me wearing it.

AD: So your parents were on board, you got backing from your parents, not resistance all the way around.

BLW: I’m sure there was times when my dad may have found what I was wearing slightly questionable but he never necessarily questioned my right to wear it.

AD: So I guess it’s not a surprise then that you ended up in a creative profession, but can you kind of add some more depth and detail to how you arrived at your decision to study design products at Royal College of Art?

BLW: It’s definitely true that that was to be a creative or to, like a long time I wanted to be an artist because I didn’t really know what other creative fields were when you’re little. But it’s always been a thing that I wanted to do and kind of needed to do. Then my aspirations to go to the Royal College of Art were kind of kickstarted by a TV program on the BBC that was on the Royal College of Art and I watched it religiously every week.

And each week they kind of followed a different department and each week I was kind of like, oh my god, I want to do millinery or, oh, I wanna do furniture and then oh, I want to do fashion or, you know, sculpture. And I just like fell in love with the idea of trying to get to that place. But I was about 16, maybe, cause I was still at the end of secondary school, maybe, and so it was slightly more, I remember when you have to go to guidance counsellors, so maybe that was in sixth form where they’re like kind of talking to you about what you’re planning to do for a career.

And when I’m already like, already like saying that’s where I want to go, I kind of got a lot of slightly blank faces, but that was what I wanted to do and that’s kind of what I started to kind of aim towards from quite early on.

AD: So, what were the college years like for you and did you get to study all the different things that you wanted to, that you interest was piqued by seeing the different departments on that documentary series?

BLW: Well, I think before I went to the RCA I went first to Kingston University for a BA and then Brighton University for a MA. And both these courses were very, very kind of materials based and very kind of ‘experimentive.’ I got a lot of kind of input from those in terms of like thinking about all different ways of being creative and then all these different types of materials that you can use to make stuff. When I got into the RCA, it was kind of combining some of the maybe more material and these kind of skills with thinking in a wider picture or understanding context of different types or nuances of design and what they’re for and this kind of thing.

When I was at the RCA, it was the last two years of Ron Arad and so we still had this platform system which kind of wasn’t always the same year on year. So different platforms would start up and some would finish depending on which visiting tutors were teaching that year and also kind of the manifestos they were interested in exploring. So this kind of setup where you had to also actively choose the platform you wanted to be on, based on the kind of manifesto that they put forward about design or a way of viewing designing, I found it really difficult for sure.

And I spent quite a lot of time kind of panicking and walking outside of the college, but it was really important to be pushed to kind of make those kind of decisions about what genre of design am I interested in. What am I going to be able to make the best work for. And also to see and talk with different designers, all already at very good level to get into the RCA.

And seeing their different ways of working methods, so like a platform, called Platform Six was much more what you maybe traditionally see as product design or make, you know, working with kind of the Dieter Rams ideology of like you know, completely taking apart a radio, every component to understand the function of each one and rethinking through the design purely based on the function of its need and this kind of thing.

And then the platform I was on was all about the city and making work in reference only to the physical location around the school and looking for ways to subvert systems that are previously setup to create work that’s intrinsically connected to the world it comes from, but then is also making something different to what’s already there. So I really enjoyed being within my own platform but being surrounded by all these different designers kind of off in their own kind of manifesto worlds to do with each platform.

I think you just, it gives you a better understanding and a better respect of the different credibility’s that design has and the different worlds it can work within depending on what, as a designer your skills are best used for, if that makes sense?

AD: It makes perfect sense and it sounds like you are also well positioned because you came into the RCA program, or platform, with a tremendous amount of technical material, hands-on knowledge already. You already had a vocabulary you could use and now it sounds like this chapter of your education was all about conceptualizing how to best use that to subvert or enhance systems or you can get a lot more conceptual, I think, when you’re not struggling to learn the materiality and the physics of how materials go together.

BLW: Yeah, definitely, Brighton especially, it’s such a materials based course and for the first like year it’s mixed with the craft course. So you really are learning and kind of designing but from a craft point of view for that first year and then you kind of choose to either specialize into materials or you don’t specialize in a material but you do more design based briefs.

But this access to this kind of level of design and then it’s like, I almost kind of would say, cause I designed teacups, I think, for my BA, two different versions of teacups. For the BA I kind of understood some parts of the history of the teacup and then it as an individual object. Then when you go to the RCA you’re also kind of like, then suddenly zooming out again, doing the kind of eames zooming out movie where you see the context of that cup within the system of the room and then the system of the house and then the system of the social and then that out and out and out.

So it kind of blows your mind but it also, I think, you know, it should challenge you.

AD: So, what was the leap from college to the professional world like for you? Was it an easy transition or was there some adjustment or did you already have some jobs that you could work on? Describe the transition.

BLW: I think for me, because after my BA I purposely took a year, I wanted a year between finishing my BA and starting the MA. So within that window of time I’d kind of worked out how to self-produce this teacup that I graduated with. I think at the beginning I was kind of being, was doing that kind of naïve thing where you think somebody is gonna come up and kind of want to produce it for you. And then I kind of did have somebody come and want to produce it, but they wanted to use it for a very different context to what it was designed for.

And I kind of had a talk with a tutor of mine from that time and they were like, why don’t you just self-produce it, if that for you fits better what it’s for and what you want to put out there. So I kind of really did a lot of kind of hands-on learning of how to make small things or something that you can produce in your kitchen and then get out and sell.

So I’d been doing that between the BA and the MA and for the first year of the MA or first six months I was still producing some small things or doing some small elements of set design. So when I graduated it wasn’t like the thing where I’d only ever been in education for the last so many years. It wasn’t as scary, because I think I had some of that kind of things that I’d tested before. But I also was very lucky that as a group we, from our platform we applied to a residency program in Vicenza because we really wanted to work with local artisans from that region and do like a locality kind of study in the same way that we’d done in London. So getting this residency and at the same time, well, actually just before this one, I was invited to do the Designers in Residence at the Design Museum in London.

And so these kind of almost started straight away after graduating, so I kind of didn’t really also stop to panic, if you get what I mean. I kind of panicked enough during my time at the RCA kind of questioning why am I here, am I good enough, what am I doing, how do I comb my hair, how do I stand up, all of these kind of, when you start to like lose any knowledge of self. I’d had that window and with the help of Jurgen and Martino kind of grappled out of it.

So I kind of wasn’t ready to go back into the kind of whole of self-doubt, so I kind of just -

AD: Jurgen Bey and Martino Gamper you’re referring to? your mentors, yeah.

BLW: Yeah, they were my tutors at the RCA and they were wonderful tutors. I see Jurgen not as often because he’s not based in the UK and Martino I see all the time because we’re neighbors from where I live now and he’s continued to be an amazing creative friend and also someone that I trust a lot for his opinion about things and about ways of working. But they were really fantastic to have as tutors because they both have a really amazing kind of strength in their own identities.

But the way that they work is quite different, so you would get quite strong views about ways of working, but you would then have to really choose, like what bits from the Martino way you, kind of worked for you and what bits of Jurgen and then kind of find your own language rather than, I don’t know, maybe if they’d been both very similar in the way that they work and approach in all stages. Whether you would have then kind of been forced to kind of question or choose a little bit how to digest that kind of information into your own work.

So I think it was, yeah, I really enjoyed having them very much as my tutors.

AD: So this residency in Vicenza came on the heels of a residency at the London Design Museum and -

BLW: Yeah, they kind of overlapped, yeah.

AD: Okay and then I know you’ve done other residencies as well, including one with the W Hotels in Mexico City. Can you talk a little bit about the residency experience and how it informs your practice?

BLW: With residencies, and not so much now, but traditionally there’s more commonly residencies for creativity but they normally don’t always look for design based practices. It’s normally a fine arts, sometimes fashion, music, performance or movement, these kind of things, in a lot of residencies. And so I think when we, when we applied for this first residency we really wanted to kind of push to show how residential, kind of residency based works could really be informative within a design based practice, or a design based manifesto.

And I think with this kind of thing, when you kind of put your wishes out there or you make, like a the Design Museum I kind of spent all the money we were given that was, like some of it was meant to be for production and some was meant to be for you to do whatever, or to grow your practice in whatever you see fit. And I kind of spent every penny I had to make this intense marquetry cabinet because I really, I wasn’t sure whether I’d get the opportunity again to make something that was really based on such complexity without necessarily having someone to purchase it at the end.

But by doing that they really allowed me to kind of put out there this kind of direction and a very specific idea of working, which then fed back to then getting residency offers off that work. So I kind of, I’m a strong believer in when you really want to work within a particular way, sometimes, you know, the best way to get that work is to start and put it out there as kind of like a calling card and then people then start to kind of call back, or hopefully do, with more opportunities that take you in that direction.

So, it kind of happened a little bit like that with the residency projects and then with the one with W Hotels, that was actually Design Miami Basel for the Designer of the Future Award. Again, Lady Luck was hanging out with me because I think that was the only year that they did the award sponsored by W Hotels and where they decided to do it in this kind of residency style. So each designer was sent to a different country where they were refurbishing or building a new W Hotel and we were asked specifically to make work about the place that we, where the hotel was going to be because Ws is trying and have some of the identity of their location within their interior design and kind of architectural styling for each hotel.

So it was perfect fit for the way in which I like to work and then when they told me a hotel was in Mexico I was more than, more than happy with this choice. And then it kind of stuck with me ever since. I’m still making work inspired by Mexico and it definitely had a massive influence on a lot of things to do with my work, especially color.

AD: Did you enjoy your time in Mexico City?

BLW: I love it! It was amazing! I had, who is now actually a very good friend of mine and his London studio is in the same warehouse as me, a wonderful designer called Fernando Laposse. He was either still interning for me, or he’d just been interning for me, but I met him when he was a student at Central Saint Martins and so when I went to Mexico City in February, he by chance was also going to be there because it was much cheaper for him to see his parents in February than on Christmas, for Christmas.

So I had the most amazing tour guide in Fernando, like taking me around all these different places of the city and the markets and explaining to me about the different murals everywhere and some of the architectural history. And it was like an amazing crash course on the city. And then I had from the hotel they like, they kind of gave me a driver cause I think they were slightly concerned when I kind of was still quite dressed up and planning to go and walk around markets and things.

So that obviously made things quite handy when you have a driver that you can kind of chauffer yourselves around. But without having the lovely driver I would have never seen the new Basilica of the Lady of Guadalupe because this was something he recommended that I might want to see because it was the day I was to go to the pyramids. Fernando was like, you know what, I’ve seen them so many times, you can do this one on your own and so I went to see the pyramids on my own and the driver just asked if I wanted to see this church and I kind of was like, well okay, you know.

Just gonna be cool, I like stained glass windows and then we literally turned up to the mother ship, which is this amazing brutalist spaceship, the new basilica with this panoramic spherical architecture and the most beautiful stained glass windows I’ve ever seen and I just, I fell in love. And the driver was slightly perplexed why I wasn’t kind of spending loads of time on the conveyer belt in front of the painting of the Lady of Guadalupe, the canvas, because I was just kind of licking the walls of these mass stained glass windows.

Yeah, that was an amazing experience. Yeah, going to Mexico City for this kind of very intense week was just mindblowing and yeah, and then I found various ways to get myself back there over the years since, because I just love Mexico City. And now I’ve been to many other parts of, not many, but a few other parts of Mexico, like Chiapas and it’s just amazing the craft and the color and details that build up the visual language of Mexico, it’s beautiful.

AD: Yeah, I love Mexico, I love Mexico City. I’m glad you had that experience and I think those intense residencies, those moments where your job is to be there and be present and just do you, you’re not on a vacation and you’re not doing client work necessarily. Those can be so enriching because you have to turn yourself into a sponge and -

BLW: Exactly yeah, I think that’s the thing where it’s, like you’re saying, is this kind of sweet spot between not being somewhere where you’re prescribed on the time of the client that you’ve got to make sure that everything you’re doing is in line with the needs of that client or the specifics of that brief and then on the other hand, if you go somewhere on holiday but you spend it kind of frantically trying to, you know, research, that doesn’t make you a very good holiday buddy [laughs].

But this kind of residency setup where there is an aim to get some things, or even the excuse to make a photo journal or digest the photos. Because we all take photos of everything everywhere, every five minutes, but it’s also having the structure around, like editing those images or going through them and making cohesive referencing from those things that kind of, I think help to really build languages or bodies of research that kind of can create very interesting works. I mean I love -

AD: Part of the process is the, not just the snapping of the photos but the actual editing process.

BLW: Yeah, I think that’s, I mean, and I’ve still got so, because last year I was doing so much travelling and it was, it was an amazing opportunity but I kind of, I still haven’t finished going through the images and it’s like, it’s almost like too much to do too many in one day. But it’s for sure, going back through, I think is very important because there’s the photographs that you may immediately photograph and that take the good Instagram picture and they can also be really amazing reference images, it can be combined.

But there’s also, a lot of images that might not be the most beautiful image in the world, might be the most boring kind of Instagram images, as I kind of learned when somebody, I think very early on when I was in Japan and I think I was on my eighth or ninth picture of rust in an hours window and I was politely trolled that not every image is one that’s necessarily needed to be shared.

It’s sometimes going back through you kind of rediscover things that you photographed that, yeah, they’re not necessarily beautiful as in a photographic image but there’s something in there that almost is even more ‘transformationable,’ ‘transformationable,’ that’s the wrong word -

AD: I love it, just taking liberties with language [laughter].

BLW: Yeah, just going dyslexic with my audio as well as my writing.

AD: But they’re always like, they’re bits of inspiration, they’re fabric swatches, in a way. They’re, they’re just information for a mood board, but not necessarily a whole story in and of themselves

BLW: Yeah, exactly.

AD: But when you put them together and then you personally go back and review it, it reopens all of those, oh, that’s why I was interested in that, oh, that sparked that, that feeling -

BLW: Exactly.

AD: And that’s what I wanna explore in this work, so that’s really interesting to me. I wanna talk about your creative process, you’re notoriously or [laughs] infamously, or famously maximalist and your work is, I think you even used the word ‘noise,’ it contains a lot of depth and texture and layers and visual noise, but not random -

BLW: Yes, okay, so it could be noise to you in the sense that different people like different styles of music, audio, okay? So it may be very noisy to someone who doesn’t like so many notes or if they really don’t like heavy metal and it visually is like heavy metal to them, then it may come across more noisy.

But I would say, like what’s important for me within, when I make work is, it has very set rhythms, there’s a lot of things going on that a lot of it can be broken down into being set rhythmical movements or visual movements that kind of have a structure to them, so that it doesn’t become too noisy from my eye/ear point of view.

AD: Yes.

BLW: If that makes sense. I know I’m flipping from visual to audio -

AD: Yeah, no, it totally makes sense, because that’s kind of where I was going with it too. There’s a lot of sound, let’s just call it sound -

BLW: Yeah.

AD: Noise makes it sound like it’s un-orchestrated and it’s not un-orchestrated, in the same way that Phil Spector did a wall of sound, his production style was a wall of sound. It’s very clear that you’re orchestrating all of these elements into a symphonic presentation. It just doesn’t, I mean what we’re saying is that the melody is maybe not discernible by everyone who is, no, it’s discernible, it’s not -

BLW: It’s just not minimal in its musical style.

AD: Minimal -

BLW: It’s more showgirl with a layer of cow bells and obviously some Bjork -

AD: Yes [laughter], great, now we’re getting -

BLW: Actually [laughter], it’s running through her music videos in my mind, oh yeah, there was a show girlie one, yeah, definitely she’s done cow bells [laughter]. Yeah, for me I would say there’s, like a lot of my work is very layered based, both visually and hopefully theoretically and like when I’m asked to describe it, I would often, well, for some particular pieces of work, I describe it as distance through detail. [0.40.00]

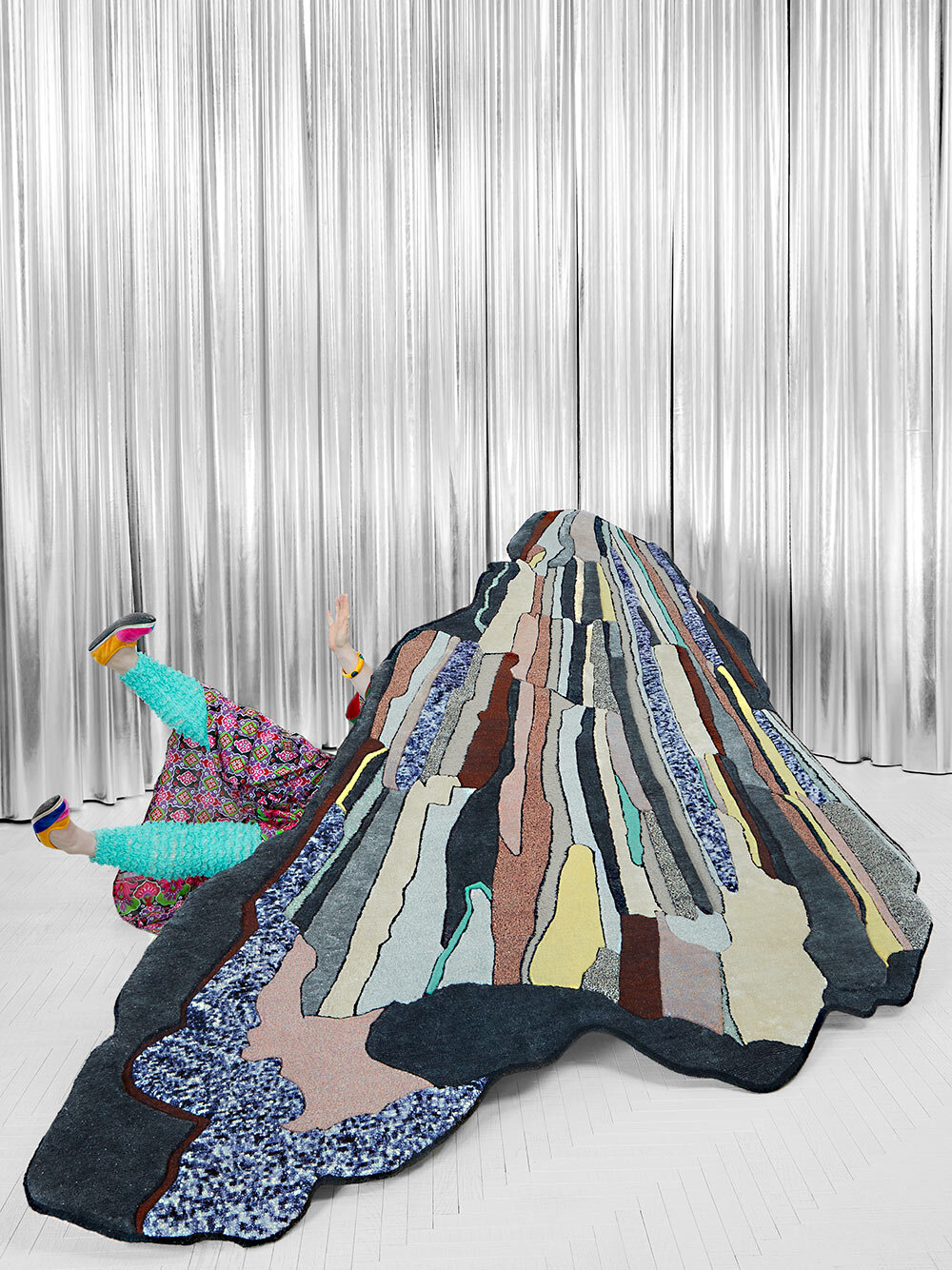

So a lot of the marquetry works especially the moon and the hot rock works from the Super Fake series, is kind of layering -

AD: Can you describe those pieces for our listeners so they can -

BLW: Yes! So imagine your Nan’s kitchen counter top with the laminate in your chicken shop, meets highbrow Memphis laminates and then kind of glittery disco laminate and very ugly kind of faux marble and it’s kind of all of those things layered and squished together to make large fantasy rocks or like fantasy woods. Yeah, the super fake kind of body of work, one of the main materials that I class as being part of that body of work is the marquetry that I do with laminates.

So that’s taking all these laminates which are kind of industrial resin and paper, kind of plastic sheets that are point eight of a millimetre thick that are normally used on table tops and kitchen tops -

AD: It’s pressure laminate, some of the brand names are Formica and Wilson and it’s a type of thing -

BLW: Sorry, I have to shout out; they’re the ones that I worked with.

AD: It’s definitely a very common building material, it’s very common in counter tops and when you say marquetry, I’m just explaining this in case our listeners aren’t familiar. It’s a form of inlay, it’s sort of like a puzzle, a jigsaw puzzle -

BLW: Yes, exactly, it’s exactly like doing a big jigsaw puzzle -

AD: So everything is flush but you have all these different laminate patterns that you’re sort of creating your own composition with -

BLW: Yeah, it’s making the laminates kind of have a conversation within themselves. So all these laminates individually, not all, but some, definitely individually I wouldn’t say are the most beautiful of surfaces, but they all are connected to very connected to different periods of time, periods of time and like mass culture, kind of aesthetics because laminate is a material that kind of only connects this through mass production because of the kind of, the industrial nature of its production.

It’s kind of every two or four years they kind of bring out, they renew their collection. So like a standard black laminate is pretty much going to stick around for a long time, but a lot of the patterned surfaces, some may only exist for the two or four years of that edition book. So I just got fascinated by all these different kind of patterns that are connected to different kind of aesthetics.

The wood grain that I used within these kind of giant rock marquetry table tops that I made is the wood grain that at that time was being installed in all the KFC shops in London. And then this kind of liney laminate that’s like, I kind of call it ‘gold lines,’ this one is one that was designed by Ettore Sotsass and so you will see it, normally in its own kind of chopped up state on Memphis furniture. I loved these kind of different worlds in which laminate hangs out in and I wanted to -

AD: You’re taking that vernacular, as you said, and they’re having a conversation with each other -

BLW: Exactly, cause for me, like that’s when you kind of almost discover how, the beauty of laminate, when you put it against itself, you kind of start to notice all the little subtleties in the surface or that one has a texture and one is super gloss, one has glitter, one has this, one has that. And you kind of can see the details within what you normally think of as being a very kind of cheaper generic surface.

AD: Yeah, it’s a way to elevate the materiality of it, but you’re also having, these cultural context that each one of these has and reference and so when you put them together, I mean I think it’s, I, I really love this about your work, you’re taking what’s not considered necessarily a luxury material and in the amount of labor and composition and concept in it you’re elevating it and at the same time not making it you’re not making it precious, but you’re also elevating, I think, all the cultural contexts within which it exists and sort of paying homage to how the systems that they all exist in.

BLW: I like to try and make things that kind of, there’s enough there that it’s like, I kind of give threads of what I’m doing but I like it to be open enough that different people will see different things. So depending on whether you have an association to a particular genre or of laminate from a period, or whether you see certain types of shapes or forms in the rock patterns that I did, some people see bacteria, some people see shells, some people see ice cream.

I love making enough space within the designs that I do for people to feedback what they’re seeing, if you get what I mean? Because I’ve always been interested in how you make these kind of connections with inanimate objects and definitely the marquetry body of work really played and kind of celebrated this kind of way of engaging in materials.

AD: Is there a highlight from your artistic design career so far in terms of a project, maybe it’s not even what you would consider to be your most successful, but it sort of inspired the most internal growth or maybe it is just a fun moment of kismet or is there something that stands out as a highlight or a milestone?

BLW: I think there’s two, they’re actually quite nicely related because the language of one is, Totem is a project, was the first project that I did with Pietro Viero who is an amazing glass artisan, that I’ve been working with ever since I did the second residency in Italy.

So we did the one in Venice and then we were invited by the Artisan Association of Vicenza to then work with their artisans after doing the Venice residency and it’s that second residency when I met Pietro and I made a single piece called Totem, which was then the first piece of, like first collection of works that I showed with Nilafur Gallery.

This project is very special to me because it was my first conversation with Pietro and we’ve now been working together over 10 years. And I’ve seen his children grow up from being like a young little boy with a very high voice to Lorrie being way taller than me, with a really deep voice. And you know, we’ve really grown, like I’ve hopefully grown as a designer and a maker and also seeing his work grow and so that project, I think, was a really special project for me because it gave me that introduction to him and then a lot of other projects have come off collaborating with Pietro right up to like last year, Salone when we did our biggest chandelier together, Kite.

Which comes from the Criss Cross language that was developed for the Mexican project, but takes it in a slightly different direction with more references from my travels in Japan. And then another project, which now feels very timely, that we did last year for the Welcome Collection in London, which was the Epidemic Jukebox, so yeah, who would know [laughs] how on the nose that project would then become for this year.

But it was a really, I mean it was a really lovely commission to be invited to do with a design group called Kin who designed the body and the carcass for this jukebox and the idea was that it would be playing various songs from history, be it like pop songs to government sponsored songs. That were all on the subject or dealt with the world that comes from an epidemic.

So I designed with Pietro, because he works with Pyrex, which is also a glass, normally most commonly known as being in your kitchen, or in a science lab. So for me making these kind of discs and cone shapes all kind of referencing the different ways in which sound has been recorded over time from the kind of cylindrical Edison early recorders that were like a wax tube, through to the mini disc and the vinyl. So we made this kind of, it’s very similar to the Totem pieces that I made for the very first pieces that I did with Pietro.

But it’s horizontal and it rotates, so you can scroll a laser dial along this body of this glass, there’s a particular glass musical instrument, glass harmonica. So it’s like there’s an actual musical instrument, it’s like lots of glass bowls and you can kind of play them like a xylophone type thing to make music. So it’s kind of a play with that and then all these different, like shapes to do with recording of sound. So yeah, this is a project that I was very proud of when we made it because it was really great to do something for a permanent exhibition and I thought the subject was really interesting.

I’ve gone to quite a few exhibitions at the Wellcome Collection and they always have an interesting curation on their displays. And then obviously this year happened [laughs] and so now it becomes an even more kind of relevant piece within my workload. So it will be interesting to see when the Welcome Collection reopens what recordings will be put onto the jukebox in response to the music and the audio things that have been made in response to this latest epidemic.

AD: It becomes a very important tool of documenting this chapter of time and a living time capsule.

BLW: I mean for me, that’s what I found fascinating when we were working on the original designs, when they sent me some of the playlists that they were playing and there were songs that I didn’t even, some that you know, are very obvious, you know they’re about a particular subject and some that are, now as being a very 80s song, but also, you know, if you properly listen to the lyrics it’s very much connected to the AIDS epidemic and this kind of dealing with the emotional side of how you deal with those kind of situations.

And I think you know, music is one of the creative fields that is so important as a way to communicate. I don’t know what you had, but even like our Prime Minister, telling you to sing happy birthday so you’ve washed your hands long enough and this going viral and there’s the other one that we all know about. You pump Staying Alive when you want to give the correct compressions to resuscitate.

Yes, of course there’s, you can say what’s the point in some of these things if they’re not like a ventilator, but at the same time finding ways for people to communicate things in a less, in a way that people can kind of understand, in a very basic way is really, really powerful. And also creating songs or music or ways for collective grief -

AD: Yeah.

BLW: To come together, is really important because we are emotional beings, that’s kind of part of the joy and the disappointment of [laughter] being a human being, for better or worse, emotion and these kind of things are part of it. So I think for me doing that project, it was so interesting to kind of really just get a little nibble into how that particular genre of creativity had become so important for translating issues around health.

AD: Yeah, fascinating. So, I mean you sort of brought something up about the joys and the grief of being human and we are definitely in a time where that’s being thrown into sharp relief. What are your daily joys and griefs, what are you going through right now?

BLW: Well, I mean I’m a very, I’ve been in a very privileged position, I’ve was working a lot the last two years with an amazing client called Perrier-Jouët. So I wasn’t in a place where I could like, not not work because we’ve been carrying on finding ways to keep the studio going during the more intense period of lockdown, but I had some pennies to get me through that, to an extent. So I definitely feel for creatives and designers may have been just off a period where they had been doing a lot of self-funded work.

To then go into a window like this, you know, it’s very difficult if your turnaround is based on a very kind of tight, in the same way, as a lot of other trades and non-creative jobs, it kind of, there’s a lot worse situations that we’ve seen that have been really difficult for people during these windows, let alone the actual reason why we’re all in lockdown with the virus.

So you know, I’ve been very lucky to not get ill and not have anybody in my family get ill but it has been, like you know, for everybody, it’s been quite an odd experience to kind of work out, if to work, how to work, why to work, you know, all of these kind of questions. Which I think on the one hand can be quite positive that we use it as a way to reflect on the larger systems that we have set up and whether we take that time to reset or reformat the focus.

But I think also on a smaller scale, it’s that complication of trying to keep motivated to keep making work. I have two wonderful designers that work with me in my studio, so I also had a responsibility to make sure that I could give them work that wasn’t gonna drive them by just archiving things to do with admin in the studio. It’s been nice the last couple of weeks to slowly be getting back to the studio and getting to work with each other, at a distance.

Because I’m a very visual/social kind of person and in the studio we really like to kind of discuss and debate and be very physical with the way that we kind of work through projects. So that’s been kind of more tricky at some points to kind of find a way to do that from the Zoom call, so yeah.

AD: So I have a very practical and very important question. It has to do with your look, you put yourself together every day in a way that’s very composed, there are a lot of elements to it. Is that fun and what’s it like when you travel? Do you have eight suitcases you need to bring with you?

BLW: Not, not eight, I’m, I’ve got my travelling down quite well, but normally, you know, I travel with at least, only a half a suitcase there so I have half a suitcase to fill. What’s the point in going somewhere if you can’t bring stuff back [laughs]. And then I was very, very luxuriously travelled on a class that I wouldn’t be able to afford by myself, by some clients and when you’re on a business class you can have three luggage.

So I’m like, guys, nobody got the memo, you can have three massive luggage, you can take whatever you want back. So this was something that I’ve become very skilled at fitting paper-mache skeletons, resin heads -

AD: Oh yeah cause these are quite careful packing too, you can’t just jam ‘em into an overstuffed suitcase.

BLW: No, it’s a very, it’s like there’s a lot of, I remember once when I was flying to Italy to go and visit Pietro and we were working on, probably it was the Totem actually, and I found, it was just before the Edison bulb thing, there was a little window where we were kind of looking that we were gonna move off Edison and then suddenly they were like a bit scarce and then there was this kind of middle ground where lots of these factories that made Edison’s realized that they needed to become even more specialist in the type of bulb they made for the new way in which those bulbs can exist, which is a more decorative genre than purely for a strong light that can last a long time and be better for the environment.

So all these kind of bonkers bulb shape started coming out and I remember I found these massive candle bulbs and I was taking one of these to Italy and I had it, as you do, rolled up inside, I think, two or three pairs of my kind of ho-down pants, which I buy from the US which are basically frilly lamb legs. [Laughs]

It was looking like a cross between big birds and yeah, like I’m herding sheep in a Victorian petticoat and so I had this bulb kind of rolled up inside these leggings and we’re going through security and this security guard got a little smirk on and he obviously thought he’d found something else in my luggage and that he was gonna just check on it to kind of embarrass me.

And I was like, you go ahead -

AD: Go right ahead sir.

BLW: You go right ahead and he was there kind of unrolling down my leggings to discover this very kind of large phallic bulb shape and then was very perplexed and I was like, it’s a lightbulb [laughter]. So you know, I’m used to finding ways to carry things in my luggage. How did we even get onto that subject? You were asking me about how I dress up. It comes from something I like to do for myself and my pleasure. So when I’m going to the studio and I’m not interacting with someone where my physical person is also part of the work, because now I’ve kind of come to terms with the fact that my identity and my work have become quite combined.

When I was younger I was very kind of, I was very, what’s the word, I was very uncomfortable with people connecting my work and how I dress and I think for a long time before, like the RCA, I was quite timid about putting pattern and color on my work because I think I wasn’t quite sure how to, like I knew how to play with it within my self and for myself but I think I wasn’t quite ready or I didn’t quite understand how to do that for something that wasn’t directly for me.

Because I knew I had a very kind of prescribed style and then I think when I was at the RCA kind of Jurgen and Martino were like, that’s, that’s something that you have that other people can’t, this kind of being able to put all this crazy stuff together. So use it and put it in your work. So yeah, now it’s more mixed, but I tend, like if I’m just going to the studio to make things, then I don’t really dress up at all.

I mean I’m wearing probably just very bad dress-up because it will be clothes that I’ve bought and gone like, argh, interesting, but not quite right. So I look more like a jumble sale reject I think, when I’m going to the studio in a kind of normal day.

AD: That’s what we have to do, we have to wear the clothing that we don’t want to preserve, so it’s all our shop clothes, which are the clothes we end up wearing every day, are the ones that can get ruined -

BLW: Yeah, yeah.

AD: We look like bedraggled clowns, or at least I do [laughs].

BLW: Yeah, that’s, I would say that that’s a strong studio look, the bedraggled clown [laughs], the unwashed clown, yeah, exactly, or the troll. Sometimes if I don’t wash my hair it just kind of can, I mean like I said, it’s very thin, so it kind of just sticks up on its own accord, like yah, like a troll doll. But when I’m doing things like the Milan Furniture Fair, I think sometimes because it’s probably the first time I’ve had a chance to dress up for ages because we’ve been working so hard in the studio, I kind of really enjoy getting to kind of dress up and play.

But then on the flipside there is a window where it becomes like, it voyeurs over into being like seen as a performance, which then I like, I’m not so into, or, yeah.

AD: You’ve got to tiptoe up to the line but not go over it.

BLW: Well, let’s say I’m a dishevelled clown in the studio. I’d like to think that I was more of a cleaned up, pretty clown during Salone but you can’t, it doesn’t work if you dress like that and you don’t expect that people might want to think you want them to take your picture or take pictures with you.

AD: Right.

BLW: You know? So these, I get and I understand, so if someone asks me then I will take a picture. I don’t, I get kind of annoyed when people don’t ask and I can see them kind of hovering, trying to take a picture and I might be in a conversation with someone else and it’s not, I’m aware that the way I look makes people feel that they can do that, but I might be talking with somebody that doesn’t want to be photographed.

So I get more kind of like, I’ll purposely move out of a shot that I know they’re trying to take, if they haven’t asked me, especially if I’m in conversation with somebody else because it’s not fair on the other person.

AD: Yeah, that’s interesting, so you’re saying it creates a social responsibility because you are willing to be non-conformist in your physical presentation, you have this extra social responsibility for those people that are around you in terms of maybe taking the attention from something and/or creating a situation in which they’re being photographed without consent and things like that -

BLW: Yeah, yeah, I think I could become more aware of the person I might be talking with might, like that might not be something they want. And so I try and kind of, yeah, but I mean when, yeah, normally if someone asks me, then of course I’ll let them take a picture or I’ll do a picture, but I’m not really, I mean if you look at my Instagram feed, maybe, I’m a very bad Instagrammer in the sense that I don’t do any of the things you’re meant to do to have lots of followers.

So I maybe post a picture with me in it, like once every 15 pictures, or less, normally less. You know, so I enjoy dressing up but I don’t necessarily, like I think I probably enjoy the fantasy of the look that I think I’m looking like, than the reality of what I probably look like [laughs] after, you know? Or in the pictures that you see, it’s like when you look back over, like the looks that you were really, really into when you were younger and you thought that was amazing.

And then you’re like well, I mean it was a look [laughs], so I prefer to be left in the fantasy of what I think it looks like when I’m creating it rather than necessarily the reality after like five hours of being with an exhibition opening or this kind of thing.

AD: I totally understand. Let’s glance into your future for a second. If you could fast forward 30 years, what do you hope to have more of in your life, or less of?

BLW: Well, in 30 years I mean I’ll be getting close to the age where I can be wearing a lot of lipstick because it will start bleeding into the cracks and I can like be one of those ladies with a harem of dogs. So you know, I’ll be an age where it’s, you can start rocking quite a good look, you know, I think [laughs] at that point. So apart from lipstick on my teeth and a harem of dogs, I mean I hope to still be making work within the design field and hopefully still being relevant [laughs], you know? I mean it’s quite a long time away, hopefully I’ll be alive, quite useful. I mean being creative and being within an industry that I love has been my aspiration from whenever I can remember. So my main goal is just to be able to keep working and creating and learning and meeting new people with, that know how to make amazing things or show me a material I’ve never seen before or that I’d go and get to visit a place or a city or location which can share with me its unique elements that build its identity and be able to make works from those things. So yeah, I kind of hope to still be working, basically [laughter].

AD: It does sound like a full vision. Do you have a project that’s going right now or something you can talk about that’s in the pipeline that our listeners should look for or pay attention to?

BLW: Well, I have a few pieces that were originally going to be at Nilafur Gallery for the Salone and I’ve been working on those pieces now, when lockdown was eased. So that’s a new chandelier piece from the Wisteria and tree language that I created originally for Perrier-Jouët who I made this sculptural piece called HyperNature and we showed it in, first we, like launched in Design Miami, first and it’s a body of work that I really, really enjoyed doing for them.

For Nilafur Gallery I wanted to make a domestic scale piece that used the, some of the narrative and the language from this work but within the context, within a scale or a framing that could work for the home or interior. So I have a chandelier piece from this body of work that will be launched at Nilafur when she reopens and a lovely mirror called Tutti Frutti Melon that’s from the first project I’ve done with a small independent mirror company in Venice.

And it was really lovely to work with them and kind of see what they do and they normally make the very kind of over the top traditional kind of baroque Venetian mirrors. So it was interesting to try and find a way to kind of work with this aesthetic that they have in a contemporary manner. So there’ll be a piece from my first experiments with them. Yeah, hopefully there’ll be a few more things coming out on the horizon -

AD: Are these pieces on view now or is there, where should we look to find them when they are on view?

BLW: So that’ll be at Nilafur Gallery in Milan, but I know that she will photograph the installation and probably make ways for it to be accessible in a digital format as a lot of the fairs and galleries and practices were all having to kind of find ways to make projects accessible in a kind of more digital manner. So probably online you’ll be able to find some stuff and I’ll definitely be updating images of the project onto my website when I have a moment.

So yeah, those things will be coming out next and then yeah, hopefully I will start on a body of work based on some of the things that I’ve been doing during lockdown, some of the drawings and also all these photographs that I took during this very extreme window of travelling that now feels, I mean it felt decadent at the time, but now it feels even more. So you know, I’ve got amazing pictures I took in the Shoe Museum when I came to give the talk in Toronto.

So there’s just stuff like this that I just want to have time to kind of digest and think about and look how to make work that kind of celebrates these things that I discovered when I was travelling, but also can relate in some way to what we’re experiencing now.

AD: Yeah, well, that will be really interesting, I look forward to that work and I really thank you for sharing your life and your story and a little glimpse into your magical brain with us.

BLW: Good, hopefully, I hope it gave a nice bit of audio glitter to you [laughter] -

AD: Definitely some audio glitter [laughs], thank you so much. Thank you for listening! To see images of Bethan Laura Wood’s work and read the show notes, click the link in the details of this episode on your podcast app, or go to Cleverpodcast.com where you can also sign up for our newsletter. Subscribe to Clever on Apple Podcasts or wherever you get your podcasts. And if you would please do us a favor and rate and review, it really does help us out. We also love it when you reach out to us on Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook, you can find us at Clever Podcast and you can find me at Amy Devers. Clever is produced by 2VDE Media with editing by Rich Stroffolino and music by El Ten Eleven. Clever’s distribution partner is Design Milk.

Thanks to our sponsors:

Adobe Wireframe

Wireframe is a new podcast from Adobe all about how user experience (UX) can help technology fit into our lives. Hosted by Khoi Vinh, Senior Director of Design at Adobe, Wireframe is a show for designers and the design-curious, leaning into how design intersects with current events and life changes. Just search “Wireframe” in your favorite podcast app or click here to start listening.

Adobe MAX

Adobe MAX is the annual creativity conference and it’s going online this year—October 20th through the 22nd. This is sure to be a creative experience like no other. Plus, it’s all free. Yep - 100% free! Featuring 56 hours of keynotes, over 350 sessions across 10 tracks, special guests and more, you won’t want to miss it. Register at max.adobe.com.

Photo by Anthony Lycett

What is your earliest memory?

Drawing probably, I have several memories of drawing in different locations, even a nightmare when one of my drawings came to life, i know I must have been small when this happened as I still fitted under my blanket my mum had made for me as a baby.

How do you feel about democratic design?

I feel it is important to have room for all types of design, that there is a place for different types of design during different times, the proportion of which types of design are more present or important during different times is dependent on the cultural and economic systems at the time or the aspirations being focused on.

What’s the best advice that you’ve ever gotten?

Stop waiting for someone else to do it and do it yourself.

Photo by Giulia Soldavini

How do you record your ideas?

Drawing, photographs and models.

What’s your current favorite tool or material to work with?

My fountain pen has been my trusty friend through lock down.

What book is on your nightstand?

Kimono, Meisen - the karun Thakar collection

Why is authenticity in design important?

I think when we have so much of everything already, if you are planning to add to the pile you need to make sure that you push yourself to bring something new to the table.

Favorite restaurant in your city?

Hai Cafe - its not fancy at all , but is a life saver when coming home late from my studio and wanting some yummy pho.

During the summer I would normally go to Towpath Cafe along the canals in East london , it is great for people watching, yummy food, and hanging with other east london creatives until the sun goes down.

And if I want to have a naughty but super tasty meal with Negroni’s , heavy rock music ( which is not my usual taste in music but the atmosphere in this little place works ) combined with tattooed cooks doing muscular things with an oven then i go to Black Axe Mangal.

What might we find on your desk right now?

Some books I am going through for references, colored pencils, my fountain pen, sketchbooks, Lino and cutting tools, paper for model making, some material samples and a laptop that needs a clean.

Who do you look up to and why?

There are many designers and artists that I look up to, Sottsass has been a designer I have long admired for his way of translating his work from the one off to the mass production, in each extreme, he makes work that is fit for its purpose but always intrinsically from his world.

Yayo Kosama is an amazing artist that has found a way to make work that exploits some of her most interment and personal issues but in a way that is one of the most engaging and open ways, I love how interactive her work is and the joy of color that explodes through especially the more recent paintings.

Closer to home as a student I met Jaime Hayon, who was super lovely and engaging. I remember when he was on the front cover of ICON magazine dressed up in an all in one lamb outfit, it gave me hope that there was room for a dress up in the design world to be taken seriously. I first met him at his showtime exhibition at the Aram gallery. I loved how he had brought the unicorn to the sometimes boring world of the bathroom fittings.

Of course Martino Gamper and Jurgen Bay have had and still have a huge effect on me and my work. I respect and admire their commitment to their visions of how to navigate, observe and comment on the different world created and being created by design.

I also really love the work of Bertjan Pot, again I admire his ability to make both work for the mass and the one off market, I love his way of exploiting materials, and techniques, my mask by him is one of my most treasured possessions.

What’s your favorite project that you’ve done and why?

I have really enjoyed the creation of the Criss Cross family of work as I have developed this with one of my longest collaborators Pietro Viero. I also am very proud of the latest piece we did together the Epidemic Jukebox for the Wellcome collection the piece and the topic it explores could not be more relevant to this yours events.

What are the last five songs you listened to?

Well a very good friend of mine Orlando weeks just released his album the Quickening, this i have been playing non stop, i think Milk breath is one of my favorite from the album.

Before this we were also playing Christine and the Queens in the studio, I may have a bit of a crush on her at the moment! We had Five Dollars on repeat but I think it has now been taken over by la vita nuova.

And by default, I can't not end up playing Bjork if asked to put a music mix on. She is my favorite musician. Vespertine is my favorite album, but I am really interested to hear the new live versions she is doing of her back catalogue this summer in Iceland. I remember seeing and hearing Cocoon for the first time. It blew my mind.

I also have been playing the blessing from Midsommar film as the soundtrack for this film was right up my street and cellophane fka twigs was another we had on hard rotation in the studio when it came out.

I made a lockdown playlist of my more calming tune’s from Mobilia on Spotify which you can find more of the songs I like in this direction.

Where can our listeners find you on the web and on social media?

Website: www.bethanlaurawood.com

Instagram: @Betrhanlaurawood

Clever is produced by 2VDE Media. Thanks to Rich Stroffolino for editing this episode.

Music in this episode courtesy of El Ten Eleven—hear more on Bandcamp.

Shoutout to Jenny Rask for designing the Clever logo.