Ep. 200: A Peek Inside Patricia Urquiola’s Curious and Magical Mind

For our very special 200th episode, we’re joined by world-renowned architect and designer Patricia Urquiola. While she’s now known internationally, growing up in Spain as the middle child she was often forgotten. She found a certain joy in this freedom of being “in between”. Declaring she’d be an architect at age 13, she went on to study with the pioneers of the time, growing her roots in systemic thinking and Magic Rationalism. Now, Studio Urquiola is a powerhouse of international design. Having already made an indelible mark on the built world, Patricia continues to be a trailblazer of the “in between” – transforming how architecture, design, art, virtual space and AI all interact today, and how we think about the future.

-

Amy Devers: Hi everyone, I’m Amy Devers and This is Clever. It’s our 200TH EPISODE and we’re celebrating with a very special guest. Today I’m talking to the phenomenal Patricia Urquiola. Patricia, is a true powerhouse of design and is widely considered to be one of the most lauded, in-demand, and influential designers of our time. Her prolific and profound contributions span Architecture, Interiors, Product, Furniture,Textiles, Fashion, Art Direction and Strategy Consulting. She’s made an indelible mark on the design of the built world through now-iconic works that offer a unique point of view, with an approachable warmth and vibrant presence. She works with important international design companies, including Alessi, B&B Italia, Cappellini, Ferragamo, Haworth, Kartell, Kvadrat, Louis Vuitton, Moroso, and Rosenthal…Recent architecture projects include Il Sereno Hotel in Como, the Room Mate Giulia Hotel in Milan, the SD96 yacht for Sanlorenzo, Das Stue Hotel in Berlin; showrooms and installations for BMW, Cassina, Missoni, and more. And since 2015 she has been the Creative Director of Cassina. There are just too many accolades to list here. She’s won several prestigious international prizes and awards, her work is exhibited in museums the world over, and she has many times been named Designer of the Year or even Designer of the Decade by prominent international design publications. Her studio, Studio Urquiola, founded In 2001 with her partner Alberto Zontone, is now a team of around 70. With 18 nationalities represented and 15 foreign languages spoken, it is a very international community with designers and architects collaborating in the most interrelated possible way. Studio Urquiola is frequently asked to design not just objects and architecture but to also think about the future of mobility, workplace and production cycles. She also leads the companies she works with to change, evolve and innovate by re-imagining entire processes, Creating links between heritage craftsmanship and innovative technologies, and upcycling waste material. Her design point of view merges humanistic, technological and social approaches and she describes her design thinking as being at the intersection of challenges and breaking prejudices, and finding unexpected connections between the familiar and the unexplored. She’s led an extraordinary life, and it plays like a who’s who of creative masterminds - she’s has worked with or been mentored by some very significant figures in design history, including Achille Castiglione, Vico Magistretti and Madellena De Padova and with boundless energy and insatiable curiosity, you’ll hear her talk about her fascination with varied interests such as modern philosophy, AI, and Judy Chicago’s The Dinner Party. For this one, you may want to follow along on the transcript. We've taken great care to hyperlink all of the significant design figures, movements, art, books, brands, and philosophers she mentions so that you can go down ALL of the rabbit holes you want. You can find that at cleverpodcast.com. Patricia’s journey is nothing short of remarkable, and she brings us right along with her on a trip that feels like part intellectual obstacle course and part magic carpet ride…. Here’s Patricia…

Patricia Urquiola: I am Patricia Urquiola. I am an architect and designer. I’m 100% Spanish, but I think 100% Milanese too because it’s the city where I live and work. We have a studio of architecture and design.

Amy: I’d love to back up to your origin story and understand how you got to be who you are now. Can you tell me the story of your childhood? You’re from Oviedo, Spain, yes?

Patricia: Álora, si si, I come from the North of Spain, as I live in Italy, they always think that I have a kind of Mediterranean origin. But I am from the North of Spain and the North of Spain is the Atlantic side and it’s facing to the ocean. It’s a kind of different powerful ID of growth. For example, I’m the second daughter of three children. Then I’m always in between.

Amy: Middle child.

Patricia: Yes, I do not see, always in between, you never know… they forget you many times. You’ve got a portion of freedom always more than your brothers. I have a big sister, but they were always focusing just to understand what to do or not to do and I had a younger brother who was the male, it was so nice, so gentle. Then I was in the middle. That’s always interesting. My father was an engineer. My mother did something, I think nice, she created a family very young and when we were born, the three of us, just she came back to study and she studied English philosophy in the 70s, and she was going to the university or doing a lot of homework at her desk in her room, I remember. Lesson…, suffering, you know? And that kind of a student attitude, I think it was nice to see her. When we were about 10 years old. I think it was something she shared with us in a way that normally you don’t share with your mother.

Amy: You saw her being driven and curious…

Patricia: Si si, and suffering, you know the exams that never ended. Things like this.

Amy: Rigorous and rugged.

Patricia: Si, and it was the end of the period of Franco, we were always moving to the South of France, because the culture was coming from there, was our salvation. As my father was Basque, obviously always Atlantic and North Ocean side, but they were just in the frontier with Bay of Biscay and I like it a lot that the grandparents, the Basque ones, they were coming always to visit.

I remember the grandmother, she was always doing for us Basque jackets, with pom-poms and I was always breaking them and then it was… my sister was always perfect! And me, I was not so. You were putting me something and something was breaking. My mother always said at the beginning I couldn’t understand why you choose that profession because you were always breaking everything at home. (Laughs)

Amy: Why were you breaking things? Were you rougher on them? Were you playing harder?

Patricia: Who knows, who knows. I’ve got the lucky thing, I had a brother, then I could always work and play with things, not only girls and Barbie things, I could play with a garage or with many other things that he had. And we were always sharing different ways of working and possibly I was curious and then you dismantle everything.

Amy: Yes, taking things apart, that makes perfect sense.

Patricia: Yes, and this never gets right anymore (laughs)…

Amy: You’ve still got it.

Patricia: Si. And then I grew up in this part of Spain where it’s a culture quite interesting, it’s about rain, about the seaside, the beach for us was always a space with the same name, but it was always relative to time because sometimes you could walk and go to the beach because it was not raining. But second thing, it was big, it was large, then you could go, the tide was the right tide. But in other moments there was no beach. This idea of beach I think gave me the idea of temporality a lot in my education.

Amy: That’s really interesting.

Patricia: Those things… you keep them with you for a long time. Or for example, my grandfather had a house just nearby that beach, we were always going in Salinas in the summertime. A lot of surfers were coming always to that beach. And in front of that house there was a big window, a very big window, the biggest in the house. And then there was a little chair in wood with three legs, a micro chair, good for me because I was really ‘picolina,’ very little.

I even ate sometimes the flies coming to the glass. Then there was, this girl has problems because I was three years, I think I was quite little, but I was there, sharing the view and then attack! Sometimes I was eating a fly. There was, why she eats flies?

Amy: Wait, you were eating flies, okay?

Patricia: I don’t know, yeah, they always say that to me, that when I was little… (Laughs) I had some problems that were already very present. (Laughter)

Amy: You were hungry for life!

Patricia: Who knows? Who knows? Poor little flies.

Amy: That sort of makes sense to me, the temporality and then the theater of the ocean in front of that framed window and you sitting there on the little three legged chair eating flies, what a picture you’ve just painted! (Laughs)

Patricia: Si, but I remember that perfectly. My mother was one of the younger sisters, she had two elder sisters and then there were always cousins, but they were always 15 years older than me and they were always coming from London, when I was young. Then I was completely absorbed by the things that were coming in summer to that house from my cousins, that was fantastic.

Amy: Yes, so aunts and cousins coming from London, bringing a sort of cosmopolitan cultural influence…

Patricia: Yes, something different, something different, yes always.

Amy: Older women have a certain…Mystique to a young girl.

Patricia: A lot of women with opinions in my house.

Amy: Yes

Patricia: A lot of crossover of that, fantastic, men blah blah blah, but I think girls were very alive. For example, another decision my parents had when I was an adolescent. I think in that period my mother, more or less when Franco died, it was the end of the 70s and my mother wanted my father to go to Ibiza to have a place there, because in Spain it’s not enough, we need a place that is changing our life because really they needed a place to trust other things. They got a very easy house in the countryside, in the period of everything very hippie and very easy. And that was another very good idea, because we were moving there in summer and you know Europeans with quite long holidays. (Laughs)

And then after school we were moving there and then everything was changing completely. Then the Mediterranean, no rules, this island, to move from one place to another place, it was something really different, very good. A lot of macrame.

Amy: Yes, end of the 70s, that would be macrame.

Patricia: Si.

Amy: Can I ask you a question, when they say they took an ‘easy house,’ what do you mean by ‘easy’?

Patricia: When you say ‘Ibiza’ and ‘house,’ you think that it was what a privilege. And in that period it was not… nobody wanted to go to Spain to Ibiza, there were not Spanish people, and it was a place, there were not a lot of policemen, very easy, with a lot of hippies, it’s low profile…my parents were about 40 years old and then they said, we need to go somewhere which is different because they got in love with that, to understand things differently. My aunty went with her family, she got another house there. Then we were a 20-30 person family, together in a garden doing family…

Amy: That sounds amazing.

Patricia: Si, super nice. I say thanks to them, really. We’re still doing it.

Amy: Oh, amazing, how wonderful to carry that on through the generations. It sounds like your family was very strong and opinionated, but also very open to new perspectives and actively seeking out changes of scenery in order to keep their minds and opinions evolving.

Patricia: I think in that period a lot of people were like this. It was a fantastic generation, people moving in that period.

Amy: And so you’re an adolescent in this period, it sounds very formative. Most teenagers go through some growing pains and have some angst or awkwardness. Sometimes getting ourselves into situations where we feel like we need to rebel or where we need to really, really try on a new identity. I’m just wondering how you sort of worked through that stage in order to become an adult?

Patricia: Can happen when you are an adolescent, it can happen when you are a bit elder than adolescent. But initially a kind of temperament which is in some way creative. Many times has a kind of fight in relation with what is the certainty of his own comfort zone, which is the family. It was not easy with my parents because they were pretty open to a lot of things and I was saying when I was 13, perhaps I would like to do architecture. And my father said, that’s fantastic. When I was young, I was not so good painting and drawing and it was so academic architecture, in his time, it was ridiculous because I think it was not about creativity, it was only about academic. I’m very happy you can get into a work which is going to be creative, but at the same time you are going to relate to space. The problem for me was not so much to get big discovery… I was the one in the middle that never knew what I was doing. It was very easy to disappear, to do things, because they were not focused on the middle one. Then what I needed, when I went to Madrid to study architecture, after two/three years of being there, I was always a good student, that was something that for me was natural. I was always reading and studying, then they didn’t look at me a lot because she’s a good student and nobody look at you when you are an adolescent. This a very good thing, you want to have freedom, good student, then they barely know anything about all the horrendous things you can do. (Laughs) That is the good news, no?

Amy: Okay, so you were stealthily taking advantage of your freedom and hiding in plain sight because you got good grades and you were the middle child.

Patricia: Si.

Amy: Beautiful, makes perfect sense.

Patricia: I never could explain very well why I needed to move from Madrid to Italy. I needed to get new experiences, to change. At the end moving from one country to the other one and getting out of my comfort zone, that is the argument. I think in some way, or because you’re discussing with family, or because you… there’s something you need to create a distance with what they gave to you, what are your roots. Even if they are fantastic, or they’re dramatic, I think many creative people, we create a distance because you need to find your roots, your personal roots. You need something that is very personal, I don’t know if it has to do with identity. Perhaps then you take 20 years to do it, or your whole life. But you need that distance because good things never come always from comfort zones.

Amy: Right, it sounds like you felt a combination of needing to sort of separate yourself from your comfort zone so that you could stand on your own two feet and really investigate what it is that is meaningful to you, separately from everything that you were offered. And I’m just wondering at that point in time, you’re looking at it with hindsight now, so you understand maybe where it came from. But at that point in time it just… what did it feel like to you? That you just needed to get to some place different?

Patricia: When you are young. You have nothing, you have nothing in your hand, that is fantastic, first thing. It’s not so bad news I think. You have a really white canvas always in your hand. I remember perfectly thinking, that’s never going to be a real place to do something. So there is nobody can tell you really what about how is going to be your path, no?

Amy: Right, right.

Patricia: There’s no idea that you’re going to have it even. But all this uncertainty, I think is interesting, is very interesting.

Amy: It’s an interesting place to be and I’ve heard from a lot of people that naiveté is actually a really beautiful… it’s that white canvas that you’re talking about. You don’t know what you don’t know, so you can’t get in your own way.

Patricia: But you move, you move, you know… for me, where I grow up, I said architecture is not in that city and then when I was Madrid, it was not enough, I needed to move and to put myself in another situation. And all these things, always they help because architecture was always the same, but the way I was approaching architecture in Madrid with the other students, we were already in the 80s and it was all about, obviously postmodernism. It was very interesting because it was very strong, it came in the 80s it’s very strong and when I moved to Milan, the idea of postmodernism and architecture was interesting, but there was Memphis movement, from Sottsass…

Amy: Yes, yes.

Patricia: There were other kinds of things more related to tools for living… there was interesting revolutions, movements that I think for me were very interesting. And at the same time rationalists, there were already teachers, there were architects as education, but they were working as designers too. They were writers, they were many things. There was a kind of magic rationalism. But these two words, they should not fit, but they fit perfectly. And that was the way, this Italian way of approaching the project, no, that for me has been really interesting. Through people like Castiglioni, the brothers Castiglioni, that they had the luck to do an exhibition, then much later in the Triennale di Milano, to do it in honor of Achille, one of them, and at the same time celebrate the work of the different brothers. Or people like Sottsass, as we were saying, that is a person who is incredible, the way he made us think about the project, always saying, for me, the real design, if I have to define, it’s something that begins when the landscape, the space for all the logical thoughts and thinking ends and begins, the space for the magic. I like a lot this idea that always… putting the concept of design always in a space which is making you move through other energies. I like it a lot. There were coming many other persons, there was one teacher that me, I liked a lot and it was Tomas Maldonado, he was coming from Argentina. He was an artist, doing very interesting contemporary art approach with his brother. It was a kind of family, very interesting in that way. He went to Europe, went to Ulm School of Design, you can imagine it’s the school after the heritage of Bauhaus, Ulm is the school that really created the concept of module, of recreating all the more severe and logical and intelligent and valid pieces of design for the reconstruction of Germany, after all what happened in all of Europe.

But after doing that he came to Milano and he came Valencia and then to Milano and he was, for me, to get into a land of rationalists, they have this kind of space for magic. It was so strange because I was coming from Ulm, then I thought really, there was not a space for that. And then they demonstrated to me… we were speaking a few times about this and it was a very nice conversation and it’s something I think was very beautiful. This was Maldonado, there was a man really interested already in progettazione ambientale, that means environmental design already when it was the beginning of this millennium. And he was already making us speak and think a lot about the idea of systemic thinking and systemic approach, systemic-systemic, all because of system, the idea of complexity. To move comfortable in a density in what can be complex. And then putting architectural design and all the project new attitudes in this, he was fantastic on that. The first new ecological thoughts in my mind came thanks to Maldonado.

Amy: That sounds like a really, really fertile time. I can hear in the way you speak about it, that it really lit you up.

Patricia: You don’t know very well what to do with all these things when you’re young. And then the time helps you to work on that.

Amy: Did you also feel like you were part of a kind of movement that was growing? Did you feel like you were a part of something?

Patricia: What I think helped me to be comfortable there, I was coming from a Spain, I was the generation, I was part of a generation of when Franco died and when I was young, then it was very important that we were changing rules, completely. They were saying, you’ve got to change a lot of things. Then when I arrived to Milano I think I was not feeling like a daughter, you know when you are a daughter you are respectful. I was feeling like we have to break rules. Look at them in a very easy way, don’t be too much respectful, which is never perfect. I always say masters must get into you, but you have to interiorize them, but you have to understand what is for you very important, from someone else, what can be a master for me can be thought in many ways. But then you cannot go out with an output that is too much relative to their work.

Amy: Right.

Patricia: You must come out with your own output, which is nothing to do with other incredible energy that you have absorbed from a master, no?

Amy: Yes.

Patricia: That perhaps is in my generation in Spain, it was very clear. Because really we had to change many things. I don’t know for me it’s normal, I hope that for many people too.

We ended now a book in Cassina, for example, a company which I’m doing a kind of art direction, no? From eight years. It’s a company that has from the beginning of my work, always the company is going to be a century now. At the same time it’s a company that we have to do this year an anniversary, a 50th anniversary.. About a decision that the company took at a certain moment, it was a company already working with incredible creative people from the 50s. But they decided to, especially in the 70s, ’73, just because now is the 50th anniversary, to create a kind of division that was called iMaestri, The Masters. Because the company began to work with the foundations of Le Corbusier, Charlotte Perriand and Jeanneret. They asked to produced, reproduce part of the éléments du régiment, you can call them in many ways, that was the way they were calling them. A collection of different pieces from the fundamentals of thinking, what are the products to arrange an ambience. They began to do it in the 60s. But in the 70s they said, that is so interesting that perhaps we have to go to other foundations and people that they’ve been really important at the beginning of rationalism. They gave the value as Rietveld. You have to know… they went even to Mackintosh, all the way to Asplund. The different architects that they’re asking to do… to the foundations. Can we reproduce and get into a production what has been important in that master, no? These things came like an organized part of the company and the production, which was always living with what the other contemporary designers were working in the company. I know this at the end has been very interesting because we are celebrating now with a book, with a very nice exhibition with it in Salone, no? In reality it was so interesting to be there with 15 foundations of the different masters. Because now we see the things from another point of view. A lot of people that were working in the company, that perhaps they passed away, as for example, Vico Magistretti, they became masters, just to explain to you, Gio Ponti or other fantastic ones. To look at that and understand how in that period of the 70s, that was the beginning of ’72 there was the Learning from Las Vegas, just to understand, that’s the book, from Venturi. And was the beginning of all this postmodern moment of ferment. The idea of the museum is not anymore, the museum, the museum, the city is broken. The domestic landscape can be even our museum. And then those pieces came into our domestic landscape as part of the values of all the last research in architecture. All these things get blended in that period especially and it’s very interesting that today those things, for us, are quite obvious. But I think Cassina as a company that really did a big frame in that way. And I’m very honored to be working with them and then we come back to the word ‘masters’ as we were saying. Masters is something that people, they had a lot to say in a certain moment and a lot to change, a lot to do in a brave way. And those pieces they got through time, filtering the values in a fantastic way. And many times they came into our domestic landscape and it’s very interesting to define the company that is still doing all this with a lot of attention. Obviously it’s not the only (laughs) argument about design. The domain of design today has a crossover much larger than furniture and representation of the first pioneers. But they are pioneers and it’s very interesting that part of my work is to take care of this, with a nice team you know?

Amy: It is very interesting because it’s a sort of stewardship of history and context and the mindset from which things grew and culture was informed. So that’s your art direction with Cassina which you’ve been doing since 2015. I do want to kind of set the stage for your very early career. From your studies in Milano to your early career, how did you get your professional footing?

Patricia: First it’s fantastic because you never think at the beginning of your career that you could ever, ever have your own studio. It’s the first thing, that is fantastic, how we get into this work because you like it, and because you think I want to work with someone who is good because as I’m never going to have my own studio, because it was for me impossible to even imagine. Then I went to work with De Padova, was a company, they were editing design. Because already in the Faculty of Architecture in Milano there was a lot of design inside my education. Design and architecture, they were two levels of project that could live together, and for me I was comfortable in that dimension. Then in De Padova, I knew that Vico Magistretti was working there because he was the companion of the woman, Maddalena De Padova, the owner of the company. Then I said if I go there perhaps I can work with him. (Laughs) And then this happened, it happened, I had been there about six years, something like this and I had the luck to work many afternoons because he was in a certain age, this designer and architect, Vico Magistretti, he was in a moment of his life, he was calm, he was a teacher in London, he was a teacher in the Royal College of Art and he was coming back. But in the day normally in the afternoon he was coming to us. It was the technical office. There were not a lot of people. Then really there was a very direct relation. He was always saying today, for me, I’m like a good doctor, sometimes I go to a convention out of my city, sometimes I go to teaching, sometimes to London, which is an honor. But then my life has a kind of routine. But you are not going to work anymore in that kind of routine. He knew already the complexity that was coming, no? And I liked that, because he would say, don’t be afraid, you’ve got sign, get on, he was always so nice, saying for me it’s been very, very important, him and Maddalena De Padova. They made me do the first piece of design, signed piece of design and things like this and co-signing. At the same time I opened a little studio with two of my friends, they were still students with me in architecture and we did a little studio. It was super nice, but it was not working. Me, I understood that I needed to go back and to do something more. Then I began to work with Piero Lissoni, that was an architect which is like a big brother, because he’s more of my generation, just a bit older than me. And he got already a studio that was running and working very well and he was working with Capellini, with companies that I thought in that period were fantastic. Then I worked with him for five years. Then I closed my studio, I worked for another studio, then I went back and then that was the very important for me, because that gave me another larger vision, another time. And then arrived already 2000 and then I said okay, I’ll open my own studio. From that moment I began to work on my own and things were much easier than what I thought. (Laughs)

Amy: That’s good news! Why were they much easier than you thought they would be?

Patricia: Because when you’re young I think many things are very easy because I think it’s important to approach what’s in your hand to live. I was comfortable, but having the responsibility of a studio and having my voice and to live from that, I thought it would be more difficult. And when I began, I think I had already a path, things were working, people were curious. And then everything was fluent. You know, there are different moments in your life that you find a wave that moves you in a fluent way. It’s not only in a professional way, I’m speaking in many ways. In relation with… I have two daughters, with 10 years of distance in between them. I’ve got to find many times the wave to get into their path, but I was more mature then, for me it was an exercise more comfortable to approach. But I think there are moments when you say, I want that, I don’t know how, but then you get into that and things are fluent. It’s not always fluent, it doesn’t have to be. Now we are in a moment, we are looking… I was listening the conversation in between Harari and Mustafa Suleyman from the Economist, Mustafa the man who wrote The Coming Wave, about AI and he’s one of the men representing AI. And Harari, the philosopher from Homo Deus. A serious conversation about AI If AI can have agency, even if it can have, as Suleyman was saying, a kind of empathic way of agency, that is a serious argument, because then we are getting into another conversation. It was a very interesting conversation. I just sent it to my daughters immediately to say, let’s get strongly informed about what is in this moment, this here, this agent of uncertainty that we have in our hands. It’s going to be very good, it’s going to be complex, the human side is going to be an aside because that’s going to come, a kind of more intelligent agency of problems that at the end, how can we manage many of those things. It’s not only about… I’m a creative, take me, my energy is not about… I am… it’s not so little arguments, it’s a serious and large argument.

Amy: It sounds like you’re avidly, voraciously curious and consuming information and really grappling with the complexity of AI and the coming implications. And sharing it with your daughters, which I love.

Patricia: I’ve got a daughter which is 18 years old and she’s beginning in London, at university to do architecture. I was saying to her… we went to see, I went to help her to buy little things in Ikea for the room, the normal things that everybody does. At the same time we went to see an exhibition of Marina Abramović, that was incredible, incredible, fine serious exhibition about the whole work. And it’s a person that I had the luck to know and share with her bits… it was very interesting to get into that. At the same time getting a book for that and saying now you’re going to get into this faculty, I was speaking about architecture in the middle of this wave. Then what is happening, then it’s very important that we cross over a lot of information, surely.

Amy: Yes, absolutely and what a beautiful picture you just painted of a very intersectional experience in terms of being with your daughter, there’s a generational component to that. There’s an art, architecture tech, AI, human evolution kind of thing going on.

Patricia: Marina is the first woman doing an exhibition in that museum that is at the end, the Royal Academy of Arts. And finally it’s done and it’s the first woman and she’s all about many, virtual and spiritual and different ways to research our possibility of communicating with others or the antennas of art. Then I think it’s very interesting because at this moment I think her energy, her human energy is very interesting. And it was very nice to connect with these things.

Amy: Yes, I love that you explained…As the antennas of art. That makes me want to ask you about the virtual and the spiritual. And the AI, what’s your relationship to all of that?

Patricia: Well, AI, I don’t know how to put so well in the middle of that. (Laughs)

Amy: Yeah.

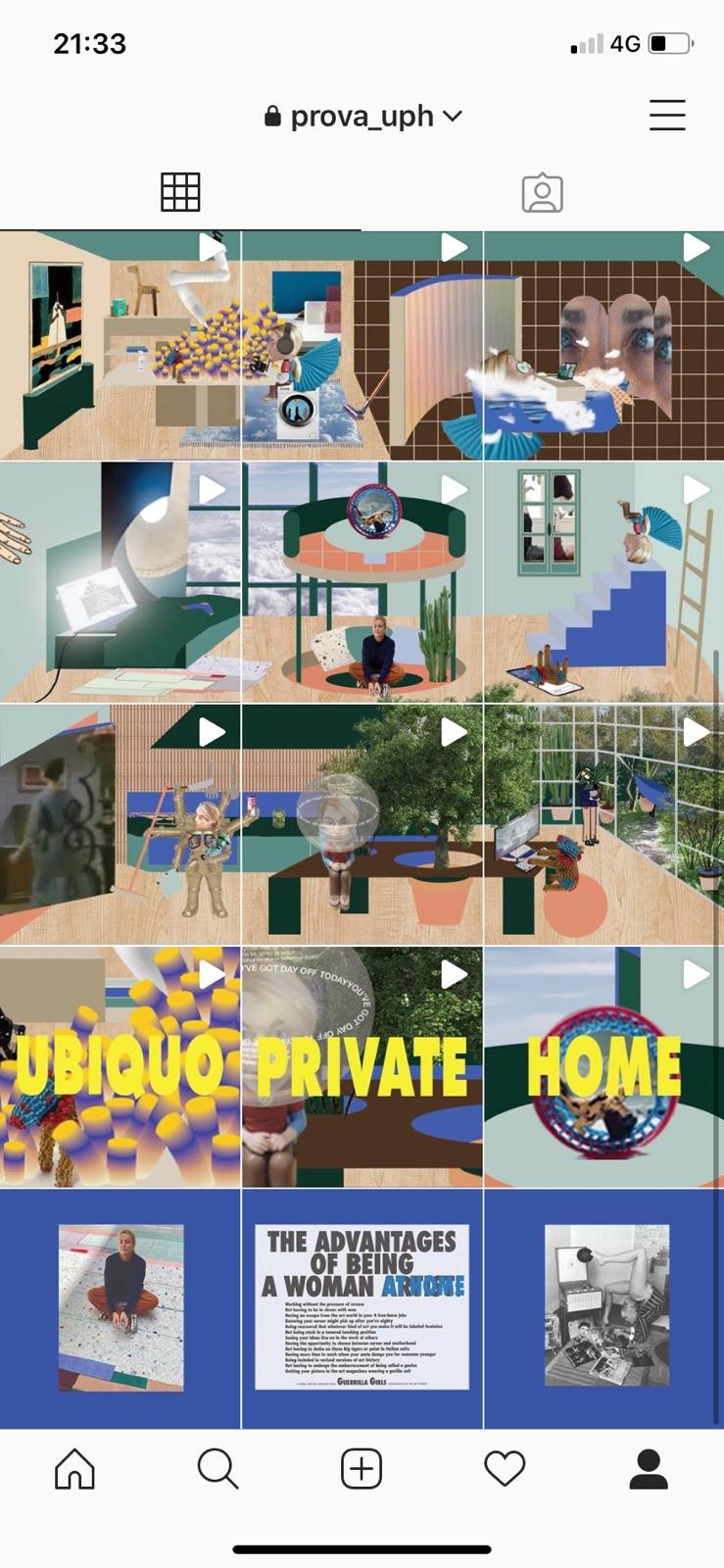

Patricia: We will see, because it’s more about intelligence that is getting more intelligent than us, perhaps it’s not about all the magic or what you were saying, which is the more spiritual. I think we are a civilization which is very relative to image, no? To the perfect image. I think in moments like this, if we have a fault or an image of us that gets into the net, in that virtual as you were saying to me, in that virtual part of our life, even we modify to make it even more perfect, this society of Image, which is I think in some way, I think in this moment it’s a moment to understand what is in the back of that. People which are interested in thinking on the other side of what is this first visual layer of image. There are many ways, many different artists or philosophers or thinkers, many ways I think. We were friends with a person that I’ve been including a lot in the work we were doing with Cassina, with different things, which is Emanuele Coccia, he’s a young philosopher, an Italian young philosopher, a teacher in the École des Hautes Études de Paris, in Paris and he teaches a little bit in Harvard the last year. He’s a man very open to interconnect many arguments. He did a book about the philosophy of home and we have a lot of nice conversations about, you know, today even as designers and architects, the way… we can control the space, it’s through the meter, how we can measure, it’s been always through the centimeters and meters, inches, it’s not important the system. But it’s not anymore enough for the virtual part then. If we are speaking about tools that are enlarging the powers of our hand, for drinking, a glass of water is the prosthesis of our little hand. The seat is like a third leg to be having a rapport, not having a moment of… like this, you can go on, all the physical prosthesis, and it’s part of my work every day, even the space and everything. But the prosthesis of our mind and he was doing very nice the tests about this, the prosthesis about our mind, yeah, very different. As the smartphone, those are prosthesis for our head. They are very different. We cannot work with measurements, the normal measurement of an architect. All this space today we live the virtual and the physical together. But if I’m an architect, I have to work in both, it’s absolutely. I don’t have the same ways of measure. Then it’s very interesting, it’s very interesting because I have a double layer to get into it, to get into that path, if I explain in simple ways, in simple words, what I want to say. Then I think we have to enlarge the instruments, to create a project. And the result of space, there are corridors of communication. I remember for example, during the pandemic, I was at home, like everyone, trying how to announce my work, I worked for example with Haworth, which is a company that we are working for 10 years. At the beginning when they asked me to not only do product, but to do a work that was a bit more enlarged, to interact with the space, to interact with the teams, different teams of work, to work in a larger way, to work as an architect. We did an hotel, Haworth, we did it in that period, even without me going there. But at the beginning of our relationship, I put a lot of energy saying to them, I’m not going to be all the time with you, because it’s in Michigan, it’s not so easy. Then let me come a few times, but it’s impossible that I’m all the time there. Let the teams, the team of architecture, the team of design, the team of engineers, to come to Milano too, then like this, I don’t ask they come a lot. But they come sufficient that we create a kind of interactive, human relationship, that then we are connected physically, mentally, you know? And then, even if we get into a virtual way, we know each other and you’ve been at my table, you’ve been in my chair and I’ve been in yours and then we were a team and we had all this experience. Then we were very comfortable. They needed to do a hotel in the city and we did it even not coming there because we knew, the team, we were so confident. I was very proud of that. And in that time, one of the things I couldn’t do, and how can I… Maxxi, which is a museum from Rome, in Italy, a good friend, a person that I know, Domitilla Dardi. She asked me, why don’t you be… part of a little project, Casa Mondo, which is a project then with FormaFantasma, which is a very interesting duo of design, Italians that I like a lot, they were giving the principles of the project. And each of us designers had to create, like for one week, three images a day in the Instagram, creating our avatar,which was for me, the argument for me was, working at home. Then I had to create for one week, it was my time. I began to work in a virtual way, doing this kind of very playful vignette, a lovely little history about this avatar, finally was me with my wings, finally was me with my dog that was doing with me a lot of things from yoga and at the time we were sharing the computer, because I want to be with my plants, he was working and they were connecting well. We were doing a lot of… in my virtual work, I have a lot of space, a certain freedom that I don’t have in my real work. In a period where I couldn’t do anything more than taking care of your plants at home, if you have them, or your family or making bread, as many people did, we shared things in different virtual ways if we were doing a map of each person, each one who could do in a virtual way, really, how was his own experience, it’s very interesting. And we did, for example, out of the box, a kind of conversation with the person that for me was very interesting and I could give them the relationship with them to others, because I couldn’t give to Cassina all the things. Then I was giving only… the only thing I had, the relation as for example, Olafur Eliasson. I got the luck to have this fantastic little relation to share with others and we did.

In other occasions I would never think to share that or to give to that value. Then corridors of virtual, the spiritual side, I think is something that perhaps today is not the conversation. I think… I was saying to you, it’s to do with the liturgic side of life, the magic side, or anything which is the wrong side, which is in the back of the perfection. Which means the human side. There is a lot, and the virtual corridors of communication, there’s a lot to work on them, a lot, a lot. And as designers, as architects.

Amy: When you described meeting the teams with Haworth and being in each other’s spaces, what I am always very impressed with is this idea that when you’re in somebody else’s space, you’re receiving so much information, so much communication from them that is non-verbal, that is simply about the energy in the space, the objects they have, the way they live that you pick up from looking around them. That helps you know a person without having to go through the process of actually asking the questions and listening to the answers. And then when you leave, you take that with you in a quantum spiritual sort of way. You’ve been in their intersubjective field and you have a sense of them that you can carry with you. And you described that so well, but also how that is what made your virtual collaboration so successful, is because you had that already.

Patricia: I choose in my life all my work is about non-verbal language. And this is something that when I was an adolescent already, I had very clear in my mind. I decided to do architecture because of that because I said in some way, it would be something creative, that means you are going to create a kind of vocabulary or a kind of language. You’re going to speak something through a space that was to study architecture, no, for me. And it’s still been for me very important today, connected to think about material, regenerated material, which is one of the most fascinating… and biomaterial, another argument which is even the one which is, I hope is coming into the real system of tools, in this five years that AI is going to change everything. I hope all of the things are coming too, because even if they’re not going to be anymore important, then we’re going to become all of us… just little gardeners. But I would like to have the tools to get into better conversation even with my plants. And to understand how to have many new tools, I’ve got to understand many things from all the other specialists…

Amy: Well, there’s the psychedelic revolution…

Patricia: It’s another thing that you know… but that is not afraid in me, I think to enlarge the human window, to a larger window, when you don’t have in front of you the gestalt relation, nature and you. But you are part of that nature, or even there are many ways to, there are a lot of philosophical ways to think about this. You are part of it, this evolving circumstance that you are part of it, with all the good and bad. I think it’s interesting that it’s coming always more clear, no?

Amy: Yes. And as it becomes more clear it also becomes more complex.

Patricia: Si. I was listening the other day, this person that was speaking about how much they are now especially listening to the language of whales, because the marine biologists, to use this technology to make contact with them, just to understand the many things that are going to be very helpful for the new kind of languages. Our masters are larger than from the humanistic ones. I think perhaps in the Oriental philosophies many times, they were really, I think, more open to understand that masters were coming from small and immense and not only coming from humanistic things, perhaps we have to learn a lot, we have to rewind a lot, no? But it’s how much in this moment with the company’s we are trying to look and say, Alora, we are rethinking the processes, the way we do, what about the whole company? Rethinking how to really understand material in another way or the way we get into the technologies that for years they were just renovated, but growing. Now we’re not so much interested in renovating and growing, we are doing the same product with a technology which is less important or less new, but perhaps we think it’s renewing other things. We are really looking to the way we produce in different perspective, across many of them. And I think that is very interesting. I think the parameters to define what is good and what is not changed so fast that we have a kind of period that there is not a set formula, and it’s very interesting what is happening in this moment from that point of view.

Amy: As you’re describing this period that we’re in, where we have to rethink everything and the parameters are changing, do you feel, do you recognize yourself as a pioneer of a new era?

Patricia: I think (laughs) I think… I say no because I feel… I am a generation which is being in the middle of passages. All of us, we are… you define yourself as a designer, we are in a moment where we say we are all designers. We understand that plants, they’ve been the first modified, they were the first designers, strong designers. What I said, pioneers. Perhaps I am part of a generation, which is in the middle of two ways. And I come from a generation that was so materialist in some way, stupidly materialist, that finally today, perhaps we were really materialist, because we understand and we focus on material to understand. (Laughs) You know, we use the word in a way that perhaps has a possibility to make me think in a positive way. Get really materialist… get us really concerned. And also I think… I hope the young generations which are in front of me, they are the ones that really have in front of them… I feel like a generation of passage more, you know what I mean?

Amy: Yeah, you’ve described that in so many ways, this temporality, these corridors of communication, the passages of your life and also…

Patricia: We are pioneers in this, possibly, because we need to approach this in a different way. We are enlarging the metrics or the measurements of what means the space. Then speak about with any integrity so architects say you know what say to me which are the new things that you cannot speak about. We are thinking about lighting and colors, this is ridiculous. This moment is how much we can give to people, a way to live in domestic space or proper spaces, that it can feel a certain wellbeing. But it’s not only about that. This moment is; we are considering things which are a bit larger than this. All the uncertainty in all these arguments that we were saying before, they are in our head and the land under our feet is a little bit moving too.

Amy: Yeah.

Patricia: Pioneers, in the way that we know that now it’s like this, you know? And anything we are touching in a project, even if it’s a little project, it’s connected to a larger object, what is material work and what is material which is a natural one, like a marble or it’s a regenerated plastic. You are connected to a hyperobject, which is something that you can’t control, you have to deal in another way. Then layers of relation, what is for us the work, in many ways at the same time, like anything you’re doing, you’re thinking about something you are producing. You have to think from the beginning the way it’s going to die, how it’s going to be dismantled. But that, I think, in some way, in the way we were working, in my experience in Italy, searching always a kind of quality of techniques, there was always this idea of understanding what about the time and the piece you are doing. What about the quality of the materials? It’s interesting, that it gets old… what means it gets old it can get old because people are still giving it value, it’s not because the material is resistant or resilient. It’s because the energy which is in the project is resilient and then people want to keep, your daughter or someone else wants to have it, or wants to recycle. It’s not only a question of resistant material, it’s a question of how many values are into a project that… can keep interest and filter in a good way, the time, that can be valuable and reused. Then it’s a complex argument which is fascinating.

Amy: Yes.

Patricia: Today we have the double layer of physical and then all these new prosthesis for our mind which are we need to work a lot on them too, to understand how to fulfill this virtual work in a lighter and different way.

Amy: Yes, it’s a new frontier and I guess that’s one of the reasons I see you as a pioneer, because you’re thinking about this and you’re thinking about what the shape, the materiality, the value, the limits, the freedom, the interactivity, the energy of this virtual space is. And I really appreciate that about you. (Laughs)

Patricia: Thank you and also me, I would like to be reborn, and to begin today. Really, really, I’m not joking. I think things are changing so much. I used too much time of my life. (Laughter)

Amy: You’re timeless, you’re timeless, your energy…

Patricia: Timeless, even is not…I think timeless can be such a dangerous argument. You have to be always the daughter of the time you’re living now. Like this you evolve and then you keep… I think you keep your adolescent side into your 80 years body, you know what I mean?

Amy: Yeah.

Patricia: I see my mother, who is 88, she’s going to be now, and she’s still having a strong… the little philosopher inside, I like her. She did a few moments of big change in her life because she’s still been very curious even about me, about my nieces, and she compares and she gets into the mood, she’s good, she’s good.

Amy: Nice, what a great model. I love that you challenged the word ‘timeless,’ I think it’s important and…

Patricia: It’s a killer, it’s a killer that word. I think it’s better you represent what is your interest in this moment. We are never the same and then I hope I had different moments and different Patricia’s in my life and I keep on creating a new one and a new one and a new one… a new one, for the time I have. For the time I have, which is just time, it’s just my time, which is always a short time, like for all of us, in relation with many things. We are enjoying this… I forgot I was speaking and someone can listen. (Laughter) That is good. I don’t know if it’s bad…. It is good because you make me not think about that.

Amy: I love it, I love it so much. (Laughs) Thank you for sharing so generously of yourself. Before we wrap up, is there anything else that you would like to broadcast about yourself, that you feel is important to share, as a daughter of the time that you’re living in?

Patricia: I think this idea of complexity is very important, to enlarge these kind of parameters for me, it’s important.

Another thing for me is beauty, it’s always… I was sending to one of my daughters to this little instrument that you can connect and you can use as a music player, some wooden tools and even a plant and you can play a very simple, you know, like a little instrument. I’m always more and more curious, how can we get more ways to start conversations which are not just our conversations. Different kinds of creative conversations with the media, if we are part of this nature and artifice altogether, more conversations, conversations, conversation I think, possibly is the democratic way of thinking that we have as humans. The dialogue and conversation is… I think it’s the only weapon we can have. You know, different conversations, find new languages for conversations.

Amy: Yes.

Patricia: But all these things are super important for me.

Amy: Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could evolve so that we could hear frequencies that we can’t currently hear or at least we could design translators that could translate frequencies of other energies that we don’t currently understand, so that we can emit instead of converse…

Patricia: Yeah, there are fantastic people doing it already!

Amy: Yeah.

Patricia: Those are the pioneers, when you said to me the word ‘pioneer,’ I would like to say to you, no, no, I want to be this upgraded pioneer, which exists now, that they are doing this. And also I think it would be fantastic to go to see Donna Haraway in Santa Cruz, she’s for me like an Eldorado. (Laughs) This incredible biologist and feminist and philosopher. And to go there one day, I would like to arrive and say just hello? I love to look sometimes on Google Maps the time from one place I like to another place I would like to be. And more or less about, I think 10 hours, I think… I will arrive to the hotel where where Judy Chicago lives in the Belen Hotel, I went to Brooklyn to see one of the works she did. There was this triangular the table with all the voice for the women that never had a voice blah blah blah, fantastic. I have the book too. I like, today to do another one, it would be with more and larger… because it’s not anymore a problem about women, it’s about many others. The dinner party, to create a kind of dinner party, in my fantasy, I go to the one woman, to the other one by car, as I did in America many times. Then in this case I will do this, from California to New Mexico…

Amy: Yeah. Road trip.

Patricia: To see two fantastic women, from past… for me they have to do a lot with future, fantastic, I like this, this is my dream, one lovely dream. (Laughs)

Amy: I love this dream. I love this dream. If I could be a fly on your road trip, but don’t eat me. (Laughter) Patricia, this has been so enjoyable, thank you so much.

Patricia: Ciao.

Amy: Hey, thanks so much for listening. For a transcript of this episode, and more about Patricia, including images of her work, and a bonus Q&A - head to cleverpodcast.com. If you like Clever, there are a number of ways you can support us: - share Clever with your friends, leave us a 5 star rating, or a kind review, support our sponsors, or hit the follow or subscribe button in your podcast app so that our new episodes will turn up in your feed. We love to hear from you on LinkedIn, Instagram and Twitter, er X - you can find us @cleverpodcast and you can find me @amydevers. Please stay tuned for upcoming announcements and bonus content. You can subscribe to our newsletter at cleverpodcast.com to make sure you don’t miss anything. Clever is hosted & produced by me, Amy Devers. With editing by Mark Zurawinski, production assistance from Ilana Nevins and Anouchka Stephan and music by El Ten Eleven. Clever is a proud member of the Surround podcast network. Visit surroundpodcasts.com to discover more of the Architecture and Design industry’s premier shows.

Patricia Urquiola, photo by Nicola Carignani

Moncloud Sofa by Patricia Urquiola for Cassina, photo by Francesco Dolfo

Cardigan Knit Lounge by Patricia Urquiola for Haworth, Haworth Showroom Chicago 2022

Venus Power by Patricia Urquiola for CC-Tapis, Photo Claudia Zalla

Haworth Hotel. Photo credit - Kendall McCaugherty, Hall+Merrick Photographers

Haworth Hotel. Photo credit - Kendall McCaugherty, Hall+Merrick Photographers

Cassina, Echoes, 50 years of iMaestri, photo by Agostino Osio

Habito by Patricia Urquiola for Max Mara

Sengu Table and Dudet small armchair by Patricia Urquiola for Cassina, photo by Valentina Sommariva

Six Senses Rome, interior by Patricia Urquiola

Casa Mondo digital exhibition, MAXXI Museum

Many thanks to this episode’s sponsors!

Please support Clever by supporting our sponsors.

Momentum - When you need to make it beautiful, innovative, and sustainable, make it with Momentum textiles and wallcoverings.

Wix Studio - Wix Studio is the platform with advanced design capabilities and integrated business solutions that gives web agencies total creative freedom to deliver complex sites.

Podcast recommendation: Travel By Design - Beyond the facade of every world-class hotel, there’s a story waiting to be heard and a destination ready to be explored.

Clever is produced and hosted by Amy Devers with editing by Mark Zurawinski, production assistance from Ilana Nevins and Anouchka Stephan, and music by El Ten Eleven.