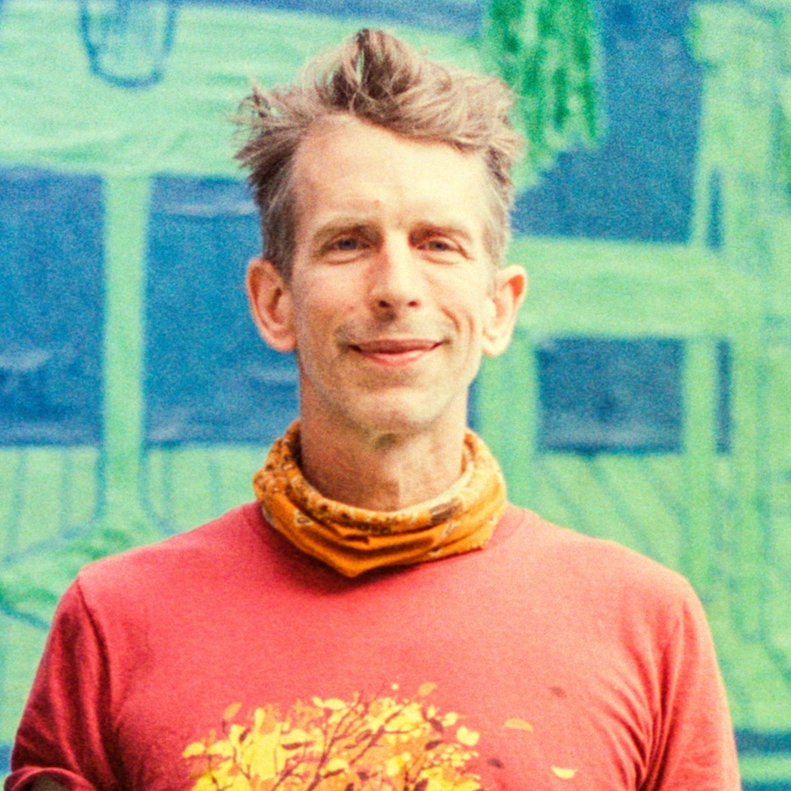

Ep. 171: Beat Baudenbacher on the Social Impact of Branding

Beat Baudenbacher was born in Switzerland, where he grew up exposed to the dynamic artistic world through his mother and the rational lens through his surgeon dad. Always fascinated by words, he fell in love with typography, and dabbled in graphic design in high school. He did an exchange year in California with no intention of pursuing design, but after his dad mentioned that a friend’s daughter was attending Art Center, a lightbulb went off and he scrambled to create a portfolio. A serendipitous trip to a bookstore led him to a job at Attik, where he met future co-founder of entertainment branding studio, loyalkaspar, David Herbruck. Since founding loyalkaspar, Beat has pushed the thinking around branding and marketing, and written an upcoming book, Somewhere Yes, that dives into how we move through this world that is shaped by branding.

Beat Baudenbacher: The way a brand is a brand shapes and marketing sells.

Amy Devers: Hi everyone, I’m Amy Devers and this is Clever. Today I’m talking to Beat Baudenbacher. Beat is Co-founder and Chief Creative Officer at loyalkaspar—perhaps you’ve seen his work for Peacock, Paramount+, MTV, ESPN, Comedy Central, CNN Originals, and many more all over the entertainment and media space. Originally from Switzerland, Beat is a Graduate of Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California. He co-founded NY-based entertainment branding agency loyalkaspar with business partner David Herbruck in 2003. His new book, out in July 2022, available for pre-order now, is called Somewhere Yes: The Search for Belonging in a World Shaped by Branding. Beat is someone who deeply questions what branding is, and the social problems it's caused. He believes the tools of branding have the capacity to help us recover from our recent dystopian trajectory as equally as they had the power to cause it. It’s a refreshing take and an eye-opening perspective, Here’s Beat…

Beat: Hi, my name is Beat, I live in Brooklyn, New York. I am the Chief Creative Officer and Co-founder of Loyalkaspar, which has turned into a branding agency. And I do it because I love design and I love figuring out the simplest and the clearest way to communicate something.

Amy: I appreciate that, simple and clear communication it’s just more important than ever. But before we get into that, let’s go back to the beginning. I’d love to hear about your formative years.

Beat: I grew up in Switzerland in a small village, about an hour and a half north east of Zurich. There’s a lake called Lake Constance that sort of… where Switzerland, Austria and Germany meet. Our town was a little bit up the hill from there. And yeah, I’m the oldest of four siblings, I have two brothers and a sister. My father was a surgeon and my mother was an artist. So there was a very interesting dynamic in my household from, ever since I remember.

There was a messiness, if you will, of the artistic household and the precision of the medical part of my family, the surgeon. Everything needed to happen for a reason. You do everything with a purpose on one hand and then on the other hand it was very, let’s see what happens.

Amy: I see how that might be, as a surgeon, everything has to be premeditated, you can’t get in there and think, oh, I’ll figure this out after I open her up! (Laughter)

Beat: You know what’s super interesting though, actually, at least my father said that there’s a good amount of creativity in that too, right? Because you need to have a roadmap of okay, once I open this body up, there’s a roadmap. But because every body is different and everything is going to be arranged a little bit differently, you need to be able to think on your feet and actually be very creative in terms of how you approach the final solution. You know what the solution needs to be. I need to have a screw in this particular bone and a plate here, but how you get there is always a little bit different.

Amy: That makes perfect sense to me. It’s a bit similar in home renovation, once you open up an old home, you don’t know what you’re going to find, but…

Beat: Exactly.

Amy: You have to be able to deal with any number of circumstances in order to get to the solution, without collapsing the house (laughter). So that’s a kind of a nice mix. Where were you in the birth order?

Beat: I’m the oldest,

Amy: Did you feel extra responsibility as the oldest?

Beat: I did, for sure. Not sort of like when I was super young, but definitely my teenage years, I definitely felt the burden, to a certain degree, or being the oldest. Which then sort of collided with me leaving first the house and then secondly, leaving the country. There was a lot of internal conflict with that because I felt like I was responsible, but I wasn’t there.

Amy: Oh, I’d love to unpack that a little bit if the responsibility that you felt, was that a kind of caretaking responsibility for your younger siblings or was that a [0.05.00] role model responsibility. Where were you feeling your internal conflict?

Beat: I think a number of those things. I think what happened during that time is my parents’ marriage was falling apart. I felt like I was leaving my siblings sort of to deal with the ramifications of that, without physically being there, which was hard. Or feeling, as the oldest, feeling responsible, if that family unit falls apart, you know, who is going to be responsible for the rest of the tribe, if you will.

Amy: How would you describe your sensitivity level? Were you also kind of processing both your parents sorrow?

Beat: Yeah, for sure. What I’ve come to learn about myself is that I feel like I have a pretty big sensor, almost like a camera. It’s sort of an HD sensor, where I kind of, I sort of take in a lot of information. I don’t always know what to do with it. But I record a lot of it. I definitely, there was definitely a good amount of processing, sorrow, pain, from afar, which wasn’t always easy.

Amy: Yeah, I relate to that. Let’s back up a little bit. In the childhood years with your mom as an artist and your dad as a surgeon, it does sound like you had a nice mix of possibly encouraging your creative side as well as your analytical side. Would that characterize your household or…

Beat: Yes.

Amy: Okay, and then what were you finding was really driving your curiosity and where were you pulled?

Beat: So, I think my mother… there’s so much to unpack here and I say that because this sort of dynamic played out in the larger context of Switzerland, which is interesting. Meaning, I don’t want to say that necessarily Switzerland is sort of restrictive in certain ways, but at the same time, there are certain expectations of how you’re supposed to live your life and the kind of things you should be interested in. Whether those are real or perceived, I think that’s definitely up for debate.

But within that, in my household, my mother was always amazingly supportive of the creative process. She had a studio where, the older we got, the more time she would spend in there. And it was always come in and play. And there’s no wrong solutions, there’s no wrong questions, you try and you see what happens.

Amy: That’s nice to have that kind unboundedness.

Beat: it was amazing. I think then from my father, it’s much more, you know, analytical in the sense that they’re definitely. Now that I think back, there definitely is sort of the, you know, try anything you want on one hand and then on the other side, it’s sort of like, but why are you trying this particular thing? You know what I mean? I definitely feel like they’re both aspects that were [0.10.00] imprinted on me from early on, for sure.

Amy: That’s interesting. The why are you trying is kind of, it sounds like it might be coming from a place of wanting you to sort of question what it is that appeals to you about what you’re trying so that you can know, is this something that you like or don’t like or do or don’t want to do. It’s not always obvious, but I do think as we grow, we learn to value… the process of learning what we don’t like is just as important as figuring out what we do like and what we are good at.

Beat: Oh 100%. I think both of those aspects, whether consciously or unconsciously, have definitely led me to where I am today and the kind of work that I do. Because I definitely feel like you need both of those aspects. There needs to be a room for play, but at the end of the day you also need to be able to rationalize your decisions and fight for them if you believe in them.

Amy: Yes, okay. So it sounds like things got a little turbulent in your adolescence, and adolescence is turbulent to begin with, I mean just because we’re bursting through the shell of our youth into the weird, flimsy new territory of adulthood. How were you sort of expressing your creativity while you were also… and finding your direction, while you were also processing your parents’ relationship and your responsibilities to your siblings?

Beat: As far as I can remember, I’ve always taken advantage of my mother’s playground, if you will. She encouraged us from an early age to be in there, in the studio with her. So that was a big aspect. I’ve always kind of felt very comfortable asking creative questions and also early on, realizing, accepting failure. Because a lot of the creative process is some things work and some things don’t and you have to try them to figure out what works and what doesn’t.

Amy: Yeah.

Beat: Being very comfortable with failure and just keep trying until you find a solution that you like. So there was that aspect.

Amy: What form was that taking for you? Were you doing graphic design or painting or music, or how was that…

Beat: Painting mostly. Yeah, canvas, acrylic, oil paints, that…We were early adopters of the McIntosh, I don’t know how early that is, but it’s actually sitting right next to me, it’s a McIntosh Classic, the first computer we had in our house. And so at some point in my teenage years I also started writing. So words were always fascinating to me, and then early on, obviously, handwritten, and then with the introduction of the computer, you know, typography in its very rudimentary form. So printing things out and then using those in other pieces of artwork, was always super interesting to me.

So in that sense I really started to kind of diverge from the work that my mother did, which was more abstract, color based. She started to use a lot of pigments and wax in a Mark Rothko kind of vibe, Jasper Johns kind of vibe. And then I started using imagery, photography, typography, again, in very sort of rudimentary ways. I would scan things, print them out and then find ways to transfer them to a canvas in some shape or form. And then start playing around with those kind of things.

So that was kind of how I got into that aspect. And then… this was probably when I was 17/18, when we graduated from high school. I don’t know if you [0.15.00]… well, you have a yearbook here, right? We don’t have yearbooks per se, but what we did was sort of like a graduation newspaper. And people would be writing, graduates would be writing articles about certain teachers or certain classes or just kind of their experiences. You’d have class photos and things like that. So I ended up volunteering to design this with a friend of mine. And her father was a graphic designer. So we spent a lot of time basically scanning and writing and photoshopping and that was sort of my first introduction to that world. Her father was, as I said, a graphic designer, and super supportive and just a really kind human being, so that was my introduction into this world.

Amy: I love that! That does sound like a pretty informative and foundational experience for you.

Beat: Yes, for sure, 100%. And I loved it!

Amy: Did that inform your decision to study graphic design or walk me through your decision to move to the US and go to Arts Center?

Beat: So a decision might be a bit of an overstatement.

Amy: Okay (laughter).

Beat: So this is where we get back to the general framework of Switzerland. I did an exchange year when I was 17, I did an exchange year in California. And I spent a year there, and I went back to Switzerland, finished my high school diploma and had absolutely no intention of doing anything with graphic design or anything visual in any shape or form. What happened was my father came back from a surgical conference and mentioned that he’d run into a friend of his whose daughter started at a school called Arts Center in Europe.

So Arts Center had a campus in Switzerland at the time. There was a sort of sister campus, Arts Center Pasadena and Arts Center Europe. It was a private school, so it wasn’t really on the radar. I was supposed to go and study economics and that summer, after he came home, I just had this sort of epiphany of, I want to try this. I spent a summer putting together a portfolio. Went to the French speaking part of Switzerland, dropped it off and you know, a little bit later I got accepted.

So in that sense, again, I don’t know if it was a decision or an impulse more. The way I ended up in Pasadena is that after first, the first two terms at Arts Center, Switzerland, they closed that campus down. And we were actually presented with two options, you could either go to Pasadena or you can go somewhere else (laughs). Because I had already lived in California for a year, I ended up going to Pasadena.

Amy: So California was not a foreign concept to you at this point, but the impulse to go to Arts Center was sort of driven by it being local, convenient and an epiphany.

Beat: Exactly.

Amy: Gotcha. And then I also read that an encounter with the Swiss military service had something to do (laughs)…I was researching you and I was like; I need to ask about that. That doesn’t make sense to my American brain.

Beat: We are required, after, at age 19 or 20, you have to do four months of basic training in the Swiss military. So that’s what I did. [0.20.00] And it was formative in the sense that it frightened me. A lot of things sort of crystalized in my brain. I realized how many bad things can happen when you put a lot of human beings in close proximity, tell them to wear the same thing and communicate a belief system to them. The reason that, let’s say encouraged me to leave Switzerland on a more permanent basis is that you’re supposed to be going back every, I think every other year for a couple of weeks. And after those first four months, I literally said, I can’t ever do this again. It solidified my pacifist beliefs and I never wanted to put on that uniform ever again. So when the opportunity presented itself to go to Arts Center in California and then later to move to New York, that was definitely in the very back of my mind. I did not want to go back and put on that uniform again.

Amy: And I can see as somebody with an extra HD sensor, that that would be a lot of, a kind of uncomfortable, constant input.

Beat: Yes, it was a really, really uncomfortable, unpleasant situation, it was very, very hard. And listen, I’m glad I did it. My grandfather was an officer, like in the army, so on a professional basis, that was his job. And my father too was an officer and so in that sense I wanted to experience it, I have this weird thing where I feel like you can’t judge something until you’ve actually either done it or seen it or experienced in some shape or form. So that’s why I wanted to go. I actually wanted to go there. There’s more… my brothers didn’t, there’s more ways to sort of substitute that military service with social services these days. So there probably would have been a way for me to get out of it. However, I did not want to do that, I wanted to experience it in order to judge it for myself. And it was a very, yes, so I’m glad I did it.

Amy: I sense there’s no disrespect in your voice, it’s just personally it was not a fit for you. And for a number of reasons. But not all people are cut out for the same things. And I also really liked what you said and I really have a lot of respect for this idea that you really can’t judge something until you’ve experienced it for yourself, or have a little bit more of a sense of actually all that’s involved. To assume that you know what’s involved in something is, I think, where we get off track a lot of times. Is we make decisions based on assumptions instead of actual experience.

Beat: Exactly. And I think we actually have a sort of saying at work too, where it’s like, our process is based on information and not assumption. I don’t know if and how this applies to the general cultural environment that we live in, but I do feel like, if we had a little bit more empathy and tried to understand somebody else’s point of view, rather than making snap judgments and assumptions about other people’s world view, [0.25.00] I think we might be a little better off. Or maybe a little less contentious, a little less conflict based, the conversations we seem to be having in the public.

Amy: It also means that people would have to be more tolerant of people not fitting cleanly into labels and boxes. So I’m assuming Arts Center was a good experience for you, even though you felt the sort of, I don’t know, interior guilt of not being with your family, as your family was kind of enduring some fracture.

Beat: Yes. It was. I absolutely loved it! It was not easy in the sense that even there, I was coming up a little bit against the sort of structures of what was expected of me. I wanted to take film classes and I wanted to take classes that didn’t fit neatly into the communication design curriculum. So I was having to fight a little bit to experience some of these other tracks that I thought were super interesting. So there was a bit of frustration with that. But the work itself, I absolutely loved. I definitely felt like I’d found my calling, for sure.

Amy: And doesn’t that feel good when you can sink into something, even though it’s incredibly difficult and you can sense that you’re growing, so you’re experiencing a deep learning curve and growing pains all at the same time. But there’s something resonating in your soul that’s like, this is what I’m supposed to be doing.

Beat: Oh, 100%. I don’t think there’s a feeling like it, this was in 1994, I think, so computers were still in the Power Mac phase. The grey box. I’m dating myself a little bit now. But I’m happy to do it just to say that there was a sort of, definitely an affinity, if not love for this tool, that was still a little new in our world. But there was something about that. Because I never, and I would still say, I’m not a good artist. Meaning my brother is an artist and my brother, his figure drawings are incredible.

I can’t draw very well. But this tool allowed me to access this place that combines imagery and typography and then ultimately motion in a way that didn’t think was possible. I didn’t know that was a thing, you know?

Amy: Yeah, well I think you sound to me like a systems thinker and on some level you were identifying with the Power Mac.

Beat: 100%, no question about it. I’m very much a systems thinker now, right, that’s what kind of branding is for me too, right? You think of these systems and how the essence of something and its visual expression, how it manifests itself across all these different touchpoints.

Amy: All the different ways you can communicate it to people who perceive it through different filters of their own, yeah.

Beat: Absolutely.

Amy: Okay, so it sounds like Arts Center was a really growth-oriented phase for you. And then it seems like you moved to New York City and not too long after founded Loyalkaspar, the branding agency that you’re still working with. Can you kind of connect those dots and talk to me about the work that you have done at Loyalkaspar in terms of pivotal projects that have informed your trajectory?

Beat: This is going to sound a bit like some random kind of [0.30.00] coincidences, right, but that’s life right, I guess.

Amy: Yeah.

Beat: Between my last two terms at Arts Center, so basically the term before I graduated, I came to New York for a week. And I met my mom here, she flew in from Switzerland. We spent a week here together in more or less harmony. (Laughs)

Amy: Pretty good for a visit from mom (laughs).

Beat: Yeah, exactly! I put together a little portfolio that I had with me with the intention of seeing if I could find some people to talk to. I ended up, I don’t know how, I ended up at Rizzoli, do you remember Rizzoli, the bookstore…

Amy: Yes.

Beat: So there was one on, West Broadway and Spring or something. So I find myself in the art/graphic design section and I pick up this book. It had a metal case; I’d never seen anything like it. And I flipped through it and I’m like, wow, this is where I want to work. I don’t know if you’ve heard of the company called Attik, it was an English design company started in Huddersfield, north of England, expanded to London and then opened a New York office a couple of years before I had gone to New York.

I look on the back of the book and it literally says their office is a couple of blocks down on West Broadway. I’m like, all right, I’m going there. So I walk in there, I have my little portfolio and I don’t know how I manage to get the nerve to do this, right, because I have a good amount of social anxiety, so that’s not usually something I would do. But I was just so inspired by that work. I walked in there, dropped off my portfolio, picked it up, went back to Los Angeles and sent a thank you card to the office manager.

And she kept the card and called me after I graduated. And so you know, wanted to see if I wanted to come and interview. That’s how I ended up there.

Amy: Oh, I love it! I love with the universe and your own inspiration just grips you enough that you follow through on an idea. You don’t let fear take over.

Beat: Yeah no, I don’t know if I would do it at this point in my career, I was just so fearless at the time (laughs). And you’re absolutely right, I’ve never sort of laid this out for myself in this kind of way. But you’re absolutely right, these two sort of pivotal moments were, the realization that graphic design at Arts Center were a thing and I literally just jumped into it. And the same thing here, right, whereas this is amazing, that’s what I want. And the universe just sort of responded, I suppose, which is pretty amazing.

Amy: Yeah, or you just do it before you have a chance to get in your own way and talk yourself out of it.

Beat: 100%. Before you start thinking, you know?

Amy: Yeah.

Beat: Before your brain tells you all the reasons why you shouldn’t.

Amy: I think maybe also working in your favor at the time was possibly a little bit of confidence, I’m assuming you did well at Arts Center and were feeling in your groove. And then a lot of naiveté, not even knowing what you were actually doing. So you didn’t know what you didn’t know.

Beat: 100%, no question about it. Because as it turns out, once I took the job, I moved to New York, it turns out… so I studied graphic design, very little motion experience [0.35.00]. There were a couple of motion classes and I get to Attik. This was the late 90s in New York and it felt to me like the motion graphics boom, right?

Television stations were getting more adventurous with their on-air graphics, where they would hire this, at that point, little known English graphic design company to make stuff for them that moved basically. And it was just sort of, they kind of threw everybody into this motion world and it was kind of like sink or swim. And that was sort of, my next epiphany was like wow, this is incredible, I can use graphic design.

I can use my interest in storytelling and filmmaking and I can use typography and words and bring all this stuff together and you can tell a story in 10 seconds.

Amy: Well, and in telling a story in 10 seconds, there’s also an incredible amount of distillation and I think this is probably leading into your branding work. But being able to understand what is important to get across in 10 seconds and how do I do that in a way that is also, carries with it enough visual impact and emotional resonance that it will be heard. It will be digested.

Beat: You’re absolutely right. I’m kind of stunned that you’re able to draw all of these things out of me! I feel like I think quite a bit about my work and my place in the world. But I hadn’t really thought about that, but you’re absolutely right. I always say that there’s still a three act structure in 10 seconds. So you’re still telling a film basically. You have set up development and conclusion, but you’re absolutely right, there’s so many things that you have to leave out and you have to distil everything basically down to its essence.

And that 100% leads to then ultimately the branding work that we’ve been doing. So you’re also right because we didn’t start out as a branding agency. We started out, I met my friend David at Attik and he was a producer there. We started writing screen plays on the side and we decided that we wanted to write more screen plays and do less design work. So after I had left my job, he was still working there, but we basically spent hours in coffee shops and at each other’s houses writing screenplays.

And one day was like, maybe we should try to do a little bit of graphic design on the side. So that’s when the idea came out of like, okay, let’s just rent a couple of desks somewhere, we’ll do a little bit of graphic design and we’ll keep writing. That was the start. And what we did back then was mostly sort of graphic design packages for VH1, MTV, the sort of Viacom universe that we still work with to this day.

But it was really mostly small graphic design packages for shows, some local work. And again, that motion work, distilling something down to five seconds, 10 seconds, ultimately led to this kind of obsession with clarity and distillation down to the essence of something and finding the visual expression for it. So I think you’re absolutely right, fascinating.

Amy: You founded Loyalkaspar with David in 2003. You’ve been at it for a while. How has the studio, agency, production company, how has it evolved and is there a project you can illustrate for us that kind of, I don’t know, paints the picture of your collaboration with David or how you both approach the work or even something that, I don’t know, broke through a personal boundary for you [0.40.00] and information who you are today?

Beat: I think from the very beginning we were sort of drawn to each other because I feel like in many ways we probably saw a sort of complementary being in the other one, you know?

Amy: Yes, and producers are system thinkers as well, so…I think you probably also had a respect for the way that you both can process a lot of moving parts.

Beat: 100%. So in that sense, from the very beginning, even though I would be physically designing elements and designing specific, whether it’s style frames or posters or logos or whatnot, our collaboration was super, super close from the very beginning. He would really help me think systematically through projects. And what I appreciate most in a great producer, in him specifically, is that a producer needs to know how to protect the creative process.

Amy: Hallelujah, say it one more time for me, please! (Laughter)

Beat: A producer’s most important job or skill is to know how to protect the creative process. Meaning that I just always knew that he had my back. He knows when to keep certain types of information from me. When to make sure I have it. When to freak me out with deadlines and when to not do that. (Laughter) From the beginning that was just always kind of how we worked.

I feel like to this day we just value other people’s input, I feel like. So whether it’s a producer has a great idea or it’s a junior designer who has a great idea, or an office manager who has a great idea, it’s just a great idea is a great idea, right? There were studios there were situations that I witnessed where definitely there was an idea hierarchy, of good ideas could only come from certain positions within a certain structure, which I think was problematic.

Amy: Yeah, I think it’s very limiting, but I think even more than that, it’s a tell, it’s a tell of insecurity. I don’t know exactly how to evaluate whether an idea is good, so I’m going to default to this hierarchy and I think that’s kind of a mess. If you’re in that situation, then you can never truly trust that the good ideas will rise to the top and get the support they deserve.

Beat: That’s exactly it. We default in other places, where we place our trust in certain positions rather than the ideas or the sort of… [0.45.00] the merits of a person rather than the position, you know what I mean?

Amy: Yeah, I also think, I mean I haven’t really spent a lot of time working in office environments or in any sort of… I’ve always been freelance, let’s say that. But I can imagine a culture that sort of says to people that a good idea can come from anywhere, is a culture where people want to contribute their best. And that is the best kind of culture I can imagine.

Beat: Yeah, I think you’re absolutely right. I think was it… six or seven years ago. We had an office in LA actually and both of our offices, I think were close to 50 people or something. And I think both David and I realized that we really did not like us getting to a size where hierarchy and structure are more important than we want them to be. You know what I mean? Because at some point…

Amy: Yeah, that’s something that you sort of need them to keep order, but it doesn’t necessarily serve the end.

Beat: Exactly and we really did not like that. We actually made a conscious decision to close the LA office and we’re back down to many more, much more manageable size and it’s much, much better. Because you you’re less likely to fall into these traps of hierarchy and positions. If it were up to me, we wouldn’t have any job titles. But I also know that that can be challenging as well. But I just love the idea of as flat a hierarchy as possible.

Amy: Yeah, I sense that about you. And in a way it’s almost in conflict with an idea of branding which is a kind of organizing principle as you’ve mentioned. It helps people organize themselves. So titles kind of do that too, in terms of, I don’t know, just knowing which boxes and buckets of responsibilities fall under my purview and which don’t.

Beat: Absolutely and you are hitting on a sort of, again, a kind of internal conflict that I struggle with a lot of times because t is our job to kind of articulate and again, strip away all the unnecessary to really communicate clearly. But what also happens is that process tends to flatten complexity. Because you need to communicate, you have two seconds for somebody to drive by a billboard and see something they like, or five seconds between a commercial on television. So you really can only communicate that much and it does flatten complexity and it tends to make a lot of things kind of black and white. And we live in a world of grey and that’s challenging, right, that is sort of internally, for me, I guess it’s a little bit of a struggle.

Amy: I resonate with that because I’m also, just in my own mental processes, trying to distal things down so that they are digestible, is the word that I keep using. And so then I kind of arrived at this idea that I want it to be digestible, but not the only bite. So how do you make things digestible, but also spark enough curiosity that you’d want to go back and learn more? In order to reinvigorate, reanimate that complexity that’s underlying the issue or whatever it is that’s being distilled down.

Beat: That’s exactly it. It’s a tease in many ways, right? [0.50.00] Can you inspire somebody, yes, to want to learn a little bit more or dig a little bit deeper and come back for the second bite.

Amy: I mean I think you are good at this because I’ve had the chance to peruse your book, which is coming out in July of 2022, ‘Somewhere, yes, the search for belonging in a world shaped by brands.’ I’ll start by saying, I have a good sense of what branding and marketing is, and I wasn’t really interested in diving into a deep treatise on brands.

But your book isn’t that. Your book is really more of a deconstruction of brands and how they are an organizing principle of society, which then informs our personal identities and they both help us make sense of the world and also flatten the complexity of the world. And I just really appreciated how deeply attuned you were to both the benefit and problems that brands present without assessing that they are positive or negative. They just are and they will be, and we need them to communicate, but we need to be aware of what we’re doing with them and how they’re influencing us so that they don’t become just a dystopic force in the world.

Beat: That is a fantastic… do you want to write something for my book? That’s the perfect way to distil it! (Laughs)

Amy: I appreciate that so much, thank you! Let’s unpack the book a little bit. I really do think it’s fascinating and I want to start from a really basic primer on what brands are. So can you just give me an overview of how we should be thinking of what brands are, as opposed to let’s say marketing or a logo or a company marks?

Beat: The simplest way to break it down is, an I have that in the book, where first of all that brand is much more than a logo, right? A logo is sort of like the singular signal that we’re familiar with. But a brand is much larger than that. A brand, I kind of… to me it sort of has two components. There’s the visual identity, but there’s also the verbal identity and it’s behavior. Meaning there are certain sorts of patterns and practices and even rituals that brands, that are inherent to brands that aren’t necessarily communicated individual identity. For example the Apple product launches, they’re kind of like these iconic rituals that you don’t get from just looking at the logo, for example. There are practices that are codified in the brand and the way a brand, in my mind at least, is different from marketing is a brand shapes and marketing sells.

Amy: It sounds to me like you’re kind of saying a brand is the character or the personality [1.00.00] of the underlying product or service, or whatever it represents. So when I see a photo of Jay-Z, I’m seeing the visual representation of Jay-Z. But my mind extrapolates everything that I know, all the contextual information I know about Jay-Z, about who he is, what he does, who he’s married to, how he acts, what’s important to him. That all comes to mind just when I see the visual representation. It sounds to me like you’re saying a brand is that contextual character that informs how a company behaves?

Beat: 100%.

Amy: I really appreciate that distinction because when you talked about how brands influenced the formation of our personal identities, at first I was a little bit like, no they don’t, I am who I am. And then I realized, no, as you grow and mature in a soup, let’s say, in an environment, brands are so prevalent that they do seep into our cultural consciousness. And as we seek to figure out who we are and express who we are to the public, brands are almost like handles.

Like handles that we can hold onto, that have a sense of shared reality. That we can say, you know, when I was growing up I liked punk rock, so certain bands were my brands that I identified my character with and it meant something about me. And I see that we all need to reach for these handles in order that other people understand too, that have a shared cultural context so that we can express who we are. And that’s really meta (laughs), how brands are able to be a part of our subconscious.

Beat: They almost turn into a shorthand, when you talk about punk rock, again, punk rock is a label, or if you want, it’s, let’s say it’s a brand, if you will, that has a lot of sub-brands within it, right? All the different punk rock bands. There’s the different fashion labels that are associated with those particular brands. There’s a certain aesthetic of like DIY, poster art, that I think of when I think of that world.

Amy: Totally.

Beat: It’s a shorthand, that’s the danger in my opinion, because punk rock is this flat, singular label that is so rich and complex underneath, you know?

Amy: Yeah.

Beat: A lot of times we don’t have the time or are unwilling to unpack that complexity. But we need the simplicity, we need the simple handle, the simple shorthand of like, I like punk rock, you like punk rock, so maybe we should punk rock together. Like we need that…

Amy: Maybe we have something in common. Maybe there’s something we can talk about if we ended up on a bus together for a while.

Beat: Exactly! Exactly! And I find that really amazing and again, it isn’t just, like punk rock by itself is not a product somebody is trying to sell necessarily. But it is still turned into this kind of like iconic term that the way I look at it, almost becomes a brand in and of itself.

Amy: It’s interesting you mentioned the sub-brands because punk rock means different things to different people depending on which era of punk rock you’re talking about, which geographical location, whether it’s you identify with the rebellious anti-establishment nature of it or whether you identify with the DIY of it. So it doesn’t necessarily really explain anything (laughs).

Beat: Yeah.

Amy: But it does help people align.

Beat: Absolutely and I think that’s… and I don’t want to get too political on this, but that’s part of the enormous power of brands, but also the real danger. Because I feel like brands mean different things to different people, right?

Amy: Yeah.

Beat: And the best brands [1.05.00] are like an open vessel for people to project their own desires and dreams and whatever else, into those, right? The strength of Make America Great Again, for example, is that it’s so open to interpretation, right? Anybody can project what they want into it. But it’s such a flat and simple term and the entire complexity is stripped out of it. At the same time, everybody can kind of project what they want into it. And that’s incredibly powerful and incredibly dangerous I think.

Amy: Yeah, let’s talk about that. The danger seems kind of obvious, but you posit that the tools of branding have the capacity to help us recover from our recent dystopian trajectory, as equally as it has the power to cause it. You tell me what the danger of branding is, but I think it is this flattening, this reductiveness, this black and white thinking that gets applied to everything. And then it almost kind of emboldens people to deactivate their own critical thinking and separates us all into, first of all separate camps.

But then the other problem is, lack of a shared reality, when brands mean different things to different people and yet we operate as though we’re understanding each other when we’re not, that…

Beat: Exactly, I think that’s really, really challenging. And I don’t know if I have, necessarily, an answer to it. Other than you know,other people call it media literacy. I almost want to call it like a brand literacy, meaning understanding that this is what happens by necessity in a world where everybody is fighting for everybody else’s attention. Where brands are fighting for our attention, like they never have before. And you’re constantly being bombarded with information, whether it’s breaking news alerts on your phone or the latest podcast you should be listening to or the latest books you should be buying, you know what I mean?

We need the simplicity because we physically cannot handle complexity, if everything was super complex. So we need that shorthand. But you’re exactly right. If these signals, if these visual soundbites that we’re getting, if those mean different things to different people, then how are we talking the same language?

Amy: How are we actually achieving some sort of resolution.

Beat: I the complexity is only visible sort of when we look past the initial soundbite, that sort of signal, the flare that is being sent by brands in our daily lives. If that’s only visible if we invest time and energy to dig a little bit deeper, and if that complexity, right, means different things to different people. Like you said, for you the image of Jay-Z brings up so many other things way beyond his music, right?

Amy: Right.

Beat: For me, it may bring up his involvement in bringing the Brooklyn Nets [1.10.00] to Brooklyn, right, or whatever else. But are we then still talking about the same thing when we talk about Jay-Z. Or how do we then need to sort of establish the kind of similar footing when we’re unpacking the complexity. I don’t know, it’s really complicated.

Amy: I think you do know because you said it, we’ve created all of these platforms where everyone is shouting, but nobody is listening and I think, I wholeheartedly believe that we have a crisis of non-listening and society and listening, actually listening to learn, not just listening to rebut or you know, one-up somebody with something funny or better, is how we get what that complexity is. And of course asking the questions, right? The questions that come from a very non-judgmental place. Like I’m just trying to understand what’s your sense of this.

Beat: Yeah, you’re absolutely right.

Amy: I do think there’s kind of a magic in a brand that you can trust because you do somehow sense that they value their… that trust with the public more than anything else, they value it more than selling whatever it is they’re selling.

Beat: think great brands can only be built on trust and truth, right? If you’re not truthful in how you represent yourself out in the public, it won’t resonate with people, regardless of whether you’re selling sneakers or whether you’re selling a worldview.

Amy: We used to call that being a ‘poser,’ if you’re a poser (laughs).

Beat: You’re absolutely right. You’re absolutely right. And I think aren’t we all looking for these kind of brands that we can sort of put our trust in? Right? At least I am, I don’t know… I think it is so challenging to hear the real voices amongst all the noise that you just mentioned. Everybody is shouting and nobody is listening, it’s super challenging.

Amy: And then there’s this deceptive layer, I think there are a lot of people who are savvy to the fact that marketers understand the trust component and will actually go out of their way to camouflage certain brand behaviors or contexts in order to maintain trust. But they’re sort of maintaining trust deceptively. And so now we have this culture of everybody just being so suspicious.

Beat: You’re absolutely right.

Amy: You have a branding agency and you value truth and trust, doesn’t that just irritate you that people are contaminating the space that you hold so dear with this performative trust building?

Beat: I mean it’s really, really hard.

Amy: But you’ve got to keep fighting the good fight, you have to, because if everything gets corrupted and polluted, we’ve got no clean water to drink.

Beat: I loved that analogy. I think I’d have something in the book or like, you know, we’ve, as a society sort of surrendered the public square to brands, but we should be able to ask them to pick up the trash that they leave behind. Clean it up, right? Clean it up!

Amy: Yes! Yes!

Beat: Put stuff in the garbage, put it in the recycling, put it where it belongs and don’t just like [1.15.00] leave it, you know? With like mental trash.

Amy: Oh my god, 100%, absolutely, be responsible for the waste by-products of what it is you’re doing and producing and that requires a sort of psychological assessment of the ways that you’re impacting society and what your responsibility is there. Thank you, preach it!

Beat: And I think we’re all suffering at the end, you know. Pick up the trash and leave some clean water behind, please.

Amy: Yes. So this has been, I want to say enjoyable, because it’s been enjoyable in that way that challenging conversations are. And I don’t mean you and I were challenging each other because we’re kind of agreeing with each other the whole time. But I do think it can be a little uncomfortable to peel back the onion and look at the layers of society and how it’s all made up and I just appreciate how you’ve done that in such an honest and truthful way in your book. So thank you for sharing your story with me Beat.

Beat: Thank you Amy so much, I really appreciate it. Your thoughtful and insightful and kind questions and thank you for helping me understand myself better.

Amy: Thank you for listening! To see images of Beat, his work and learn more about him, read our show post: click the link in the details of this episode on your podcast app, or go to cleverpodcast.com where you can also sign up for our newsletter subscribe to Clever on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts. We love it when you take the extra step to rate and review - it really does help us out! We also love chatting with you on Twitter, Instagram and Facebook - you can find us @cleverpodcast. You can find me, @amydevers. Clever is hosted & produced by me, Amy Devers. With editing by Rich Stroffolino, production assistance from Ilana Nevins and Anouchka Stephan and music by El Ten Eleven. Clever is part of the Airwave Media podcast network. Visit airwavemedia.com to discover more great shows. They curate the best of them, so you don’t have to.

Beat and David

What is your earliest memory?

My family spent a couple of years in Lambaréné, Gabon, Africa, where my dad worked at the Albert Schweitzer Hospital. When I was about 4, I got really sick with Malaria, and I remember lying in bed, looking at my mom through a curtain of mosquito netting.

How do you feel about democratic design?

I believe in democracy and I believe in design. Both should be available to as many people as possible. And improve the lives of as many people as possible. The one thing I don’t believe in is treating either of them as a commodity.

Page from Beat’s upcoming Somewhere Yes book. Preorder now!

Directing Adam Scott

How do you record your ideas?

I feel like I’ve tried dozens of note-taking apps. The one that has stuck the most is DAY ONE. I use that for raw notes. I used Storyist for more comprehensive chapters while writing the book. When I start to add visuals, I use Keynote and InDesign. But frankly, I’ve started to use the “if it’s important enough, I’ll remember” method more and more. For better or worse…

What’s your current favorite tool or material to work with?

Adobe Illustrator and the Fuji X-T3.

What book is on your nightstand?

STAMPED FROM THE BEGINNING by Ibram X. Kendi, A PROMISED LAND by Barack Obama, SAPIENS by by Yuval Noah Harari and A SECRET HISTORY by Donna Tartt.

Why is authenticity in design important?

I think people relate most to REAL things. Fake news, fake people, fake design are pretty quickly exposed as such. So if the purpose of design (or brands) is to create REAL connections with people, the design has to be authentic.

Beat and David, early days

What might we find on your desk right now?

A LEGO rocket, a Fuji camera and a chap stick.

Who do you look up to and why?

During the writing of the SOMEWHERE YES, Marshall McLuhan’s THE MEDIUM IS THE MASSAGE and Peter Mendelsund’s WHAT WE SEE WHEN WE READ were my constant companions. They both do an excellent job at weaving together a narrative through words and imagery. I was trying to find my own narrative structure and both of those books were great reference points for different reasons.

What’s your favorite project that you’ve done and why?

It’s hard to choose between your children! Favorite may also be too broad a term; there are some projects that yield a great end result but the process may have been treacherous, and for other projects it’s the other way round. A recent project that I think is an important one were the media programs for GREENWOOD RISING, a new history center at the heart of Tulsa’s Greenwood district. It depicts the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, honoring the legacy of Black Wall Street before and after the horrific event. As you can imagine, the subject matter is extremely tough and challenging, so the process was not easy. But if you can use visual storytelling as a tool to shed light on history and help create more of a shared sense of reality, that’s extremely powerful, important and satisfying.

LK Brand Pyramid

LK Studio

What are the last five songs you listened to?

THUNDER ROAD by Bruce Springsteen

BORN SLIPPY by Underworld

YOU’RE THE ONE by Shane McGowan & The Popes

IMMERFORT by Herbert Grönemeyer

BOTH SIDES NOW by Emilia Jones (CODA Soundtrack)

Where can our listeners find you on the web and on social media?

loyalkaspar.com

Clever is produced and hosted by Amy Devers with editing by Rich Stroffolino, production assistance from Ilana Nevins and Anouchka Stephan, and music by El Ten Eleven.