Ep. 234: From Band to CCO: Laura Stein’s Road to Creative Leadership

Chief Creative Officer of Bruce Mau Design, Laura Stein grew up on Nun’s Island outside of Montreal, a near utopia where kids never had to cross the street. Her psychiatrist father and museum-involved mother cultivated curiosity about emotions, critical thinking, and the arts. A move to Texas in her teens resulted in quite a culture shock. Laura found an innate knack for peer reviews and analysis, which became a strength throughout the rest of her academic and professional career. Originally graduating with a degree in English, she returned to school to study art, where she found not only her community, but her band mates. From there, it was a wild ride - record signing (Sub Pop,) touring, and navigating all the ups and downs of being in a girl band in the ‘90s – the ultimate creative boot camp. Now in leadership at Bruce Mau Design, she’s deploying the wisdom garnered from all these experiences to build a culture focused on keeping possibility alive.

Subscribe to our substack to learn more about Laura.

Learn more about Laura on Linkedin and about Bruce Mau Design on their website and instagram.

Laura Stein: That was a big moment where I was like, oh, you can tell stories in design. I didn't really understand that before. [0.45.00] But suddenly, it's like, oh, okay, yeah, all these things that we're making or telling a story, even before you hear the music, there's something going on there that people are receiving.

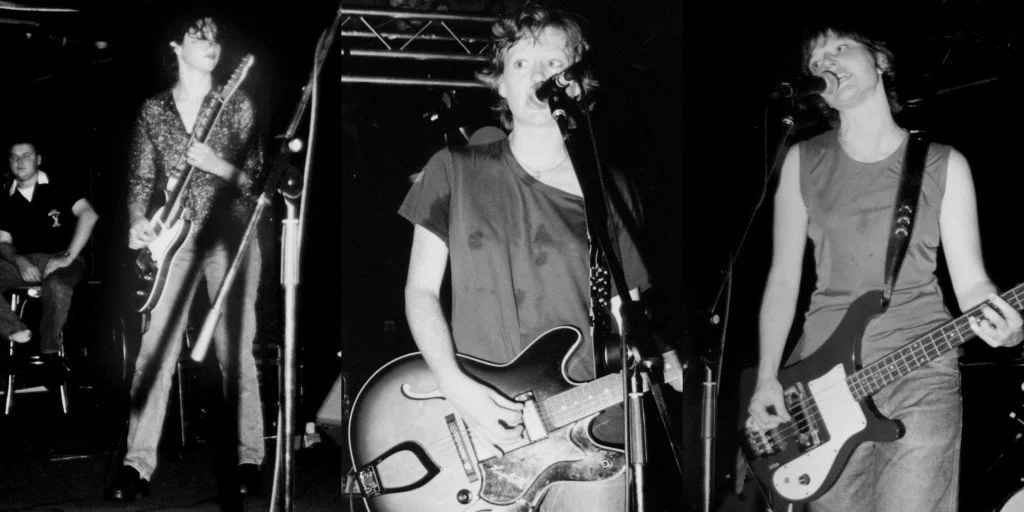

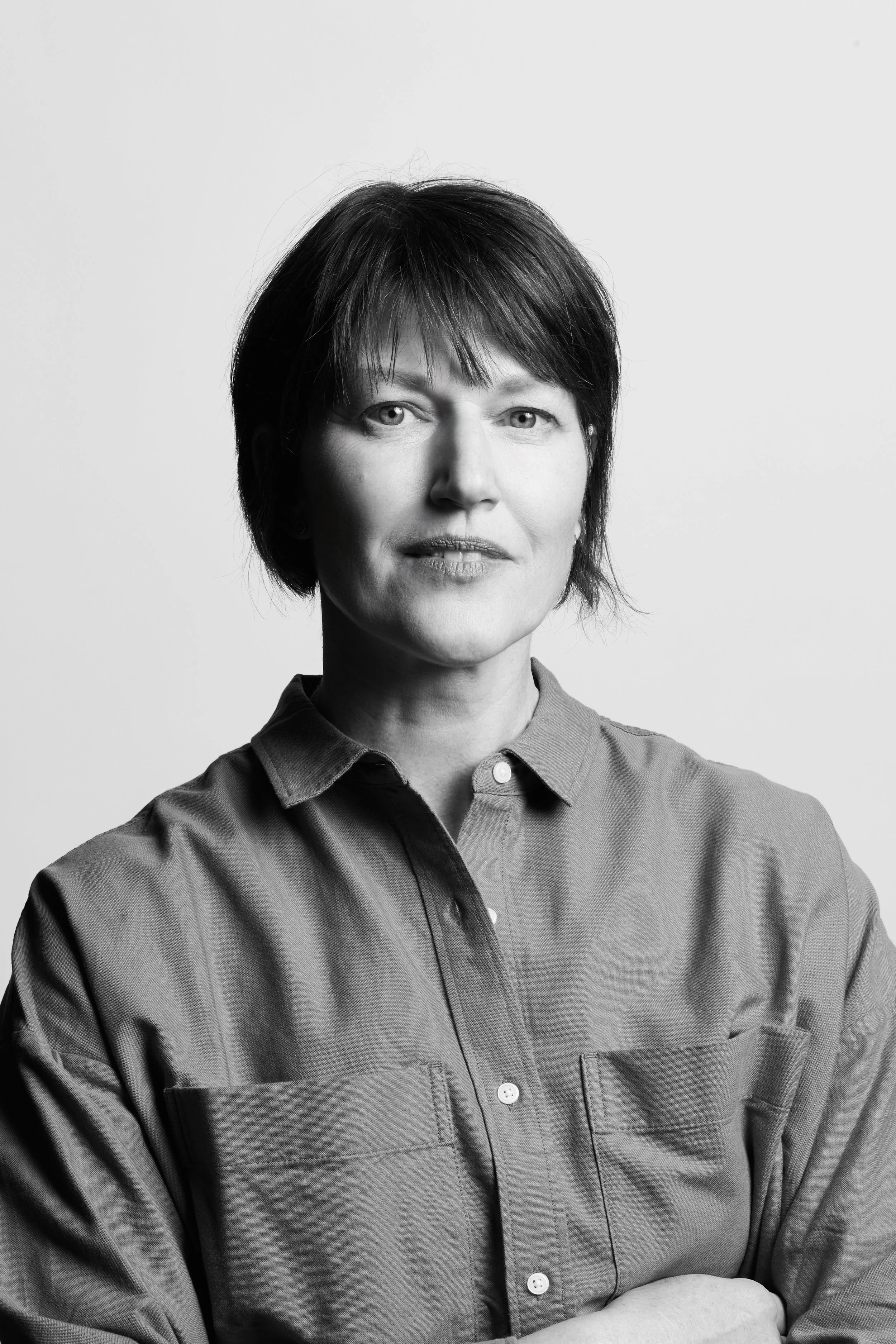

Amy Devers: I’m Amy Devers and this is Clever. Today I’m talking to Laura Stein, a strategically-minded design leader and culture builder who serves as the Chief Creative Officer of the award-winning branding firm, Bruce Mau Design. Her work crosses fields of culture, fashion, architecture, technology, education, and place / across brand, print, motion, digital, and environmental. And with extensive experience in branding, she’s led global rebrands of organizations including Sonos, ASICS, and Linksys. She’s been recognized by D&AD, and Cannes lions, and lectured across prestigious conferences like Brand New, DesignThinkers, and FITC. Impressive yes, but wait until you hear her story… It's epic. Before her journey to the c-suite of design, Laura Stein rode the wave of the Seattle grunge scene in the 90s with her all-female band, JALE as a singer and bass guitarist. Signed to Sub Pop records, they made music, records, music videos, and toured the world. And as she found herself designing merch, t-shirts, album art and flyers… she also found a calling. As you’ll hear, this was a layered, high-intensity experience that was foundational to her development as both a creative leader, and a total badass… here’s Laura

Laura Stein: My name is Laura Stein. I live in Toronto, Canada, and I lead a design team at Bruce Mao Design. We love making beautiful, culturally rich identities, putting them out into the world, and moving organizations forward, making things a little bit better for the organization and for everybody who is part of that organization.

Amy: That sounds pretty robust, and I want to trace the path that you took to get there, and I kind of want to start at the beginning. So if you would set the stage for us, I would love to hear a bit about your formative years, where you grew up, what kind of family dynamic you were in and, you know, what kinds of things fascinated you as a child.

Laura: I grew up in Montreal. Actually just outside Montreal in a place called Nuns’ Island, which was essentially owned by nuns for a long time, and then became a kind of planned neighborhood in the late 60s, early 70s, with all sorts of kind of utopian design principles around how to build a little community, which was super cool. It was a little island, it was an actual island, and there were a few different streets there, but they designed it so that children never had to cross the street.

Amy: What?

Laura: So it became this kind of really interesting thing with lots of underpasses and parks, and it was pretty great. It was a great place, especially at the time I grew up, you know, children ran wild a little bit more maybe than they did today.

Amy: Yeah, I grew up in those years too. (Laughs) So a whole island full of underpasses sounds like an amusement park. It sounds like a great place for growing up. (Laughter)

Laura: It was really great, and it was really interesting. I mean, Montreal is a super cool place where there is, you know, a lot of French and a lot of English, and this place was a nice mix of those things and a lot of different kinds of families who lived there. My dad was a psychiatrist, and my mom was a nurse, which was one of the few jobs that were kind of open to her at a certain time. She later became really involved in museums.

Amy: Okay, that sounds relevant.

Laura: But one of the things that was really interesting about my childhood was growing up in this kind of world of thinking about emotions and the brain and why we do things and why we feel things, and one of the really formative books of my childhood was called T.A. for Tots or Transactional Analysis for Tots, and this was a kid's book all around the way we think and feel, and I think I… I mean I took so much from that book. I still use the framework in that book. It's like 70s-style illustrations, and this kind of language that kids could really understand, this notion of cold ‘pricklies’ when somebody does something that makes you feel bad, this idea of warm fuzzies. It's really…

Amy: Oh, helping you name all of those sort of…

Laura: Emotions and things that happen between people. So I grew up in this family. I have two sisters who, you know, this was just part of how we kind of navigated the world. My mom was able to stay home with us when we were really young, and she really, I guess, brought in the arts aspect of our childhood. I went to my first art show with her. I really remember it very clearly. You know, growing up in Montreal, it can be… the weather can be a little bit, I don't know, forbidding. (Laughs) [0.05.00] So she would throw up these massive rolls of, like, craft paper, and we would all just kind of draw, like me and my sisters and our neighborhood friends, we'd just draw on these massive pieces of craft paper, all collaboratively take them down, start up again.

Amy: Oh, wow. So not only the arts, but the concept of collaboration was also brought in at the same time, so they were baked in together.

Laura: Yeah.

Amy: Which is very interesting, viewing it as a group activity as opposed to a solitary activity or something that you would do side-by-side. What about your dynamic with your sisters? Where are you in the birth order, and how was all that?

Laura: I am first, and they are twins. So they're two and a half years younger than me. So that's why there's lots of sort of collaborative things going on, but also why I did escape to my little space, and do lots of solitary kinds of activities also. So I was a fairly introverted kind of kid, but always felt really comfortable in these kind of little groups of people that were two or three. It was kind of a nice sweet spot for me, I think, because of the way I grew up.

Amy: Did you feel classic big sister responsibility?

Laura: I did.I definitely felt the big sister kind of responsibility.

Amy: I don't know if it's escapable, honestly.

Laura: Yeah, a little bit. We're really close, and we all live in the same city, which is amazing.

Amy: Oh, that's awesome.

Laura: We've each taken different aspects of our growing up. One of my sisters is a child psychiatrist. Another sister teaches at an art design college, and she's a futurist as well, so thinks about how we imagine the future and how we talk about it. [0.10.00] Yeah, so we're all kind of in different pockets of our little petri dish.

Amy: What a powerful trio, though, in the way that you're using your agency in the world and supporting each other. I like that.

Laura: Yeah, I've always felt there's something about having three girls in the family. There's something about being a kind of powerful force. I don't know, I've always felt that as part of this. Any boyfriends that came in, I think, as we were in high school too, maybe felt it as well in a maybe not great way. It's like, oh, no, there's all of them now. (Laughter)

Amy: Right. Well, you can't win one unless you can win all three of them.

Laura: That's right.

Amy: That's actually a good test. So, the teenage years are such interesting years. I'm always so fascinated by them because it's such a process of transformation where we're shedding our old skin and kind of trying on the new skin of the person that we're becoming, and that externalizes and internalizes in a myriad of different ways because you're metamorphosizing it so fast. What was your teenage years like? What was the development process like for you?

Laura: Well, I had a couple of big moments when I was growing up. One of them was moving to Dallas, Texas from Montreal, which was very different.

Amy: Oh, my God. That's huge.

Laura: It was a big culture shock.

Amy: How old?

Laura: I was 11 years old, and then we stayed there for two years and then moved back to Canada, moved to Toronto actually after that. I think all of us experienced the shock. One of my sisters, I think, didn't wash her hair for a year because she was like a bit of a trauma. But it was an interesting peek into a wider world that I think was formative.

Amy: Had you done much traveling before that?

Laura: Not tons, no and had never been to that southwest U.S. kind of thing, although my mother is American, so she's from Oklahoma. She anticipated certain things and tried to help us navigate as best as possible.

Amy: Why the move?

Laura: Well, I mean, there was an interesting time in Quebec where there was kind of like an exodus of English-speaking people as Quebec was considering separation. So there was a whole referendum around separating from Canada, and this kind of conversation had gone on for years. But people, sort of English-speaking people, I think, got nervous and trickled out, and my dad got an offer to teach in Dallas. And so we went. It was an adventure.

Amy: Sounds like it. Yeah. Well, having an American mother from Oklahoma probably really did help. But as an 11-year-old, you know, it's just rough to get uprooted from everything you've ever known and all your friends.

Laura: I think it definitely solidified my introversion. I became pretty quiet. I think I was pretty quiet for the first year I was there, and I started to come out of my shell a little bit in the second year. But I'm also a person who is okay with change, and I don't know if that helped that at all, just having survived sort of big changes. I kind of enjoy moving in different places and living in different spots, and I don't know if that was part of helping me be fine with it. I don't know.

Amy: It must have been. I mean your learning to cope with it must have been the thing that gave you permission to trust yourself when moving through change, to know that you can rely on this strong internal system that's going to support you through it.

Laura: Yeah, that it'll be okay. It'll be okay.

Amy: And I'll figure it out.

Laura: Yeah, I think that's right.

Amy: And if I have to be quiet for a year, that's not the end of the world. I'm okay there, too. [0.15.00]

Laura: Yeah, I think that's totally true.

Amy: Very interesting. What was the other thing that you were going to say happened in your teenage years? You said there were two big things.

Laura: Well, I think I was thinking about going back to… then going to Toronto, which was another big move. And at the time, I moved when it was grade eight, and that's a tough time for kids generally. I think that is maybe one of the hardest ages. And so just going back to a place that was already quite cliquey and well-formed was also a little bit challenging.

Amy: Yeah, now it's about survival socially and having to figure out, first of all, not only where do you fit, but how to then carve the pathway into fitting there. And it might mean trying a few different people on at first.

Laura: Yeah. I always liked art, and when I was younger, I thought, oh, maybe I'll be… in my mind, when I was a kid, I had this idea, oh, I'll be a cartoonist. And I really wanted to draw cartoons in the manner of like Peanuts and drew my dog all the time and had these sorts of stories around my dog. And then as I was in high school though, the art piece sort of dropped away a little bit because I was maybe feeling less confident generally or less like this is something I can really excel at. And I really liked it, but I stopped doing it and thought about trying to do other things.

Amy: Okay, so that sounds like kind of an interesting chapter because you did go to art school for college. So somehow you found your way back to it.

Laura: Yeah. Well, so I had this moment in high school. I feel like I have… you were saying, you know, you’re shedding skins and I feel like every few years I shed a new skin.

Amy: That’s good, that's healthy, that's constant growth.

Laura: I think so. And I had a great English teacher who introduced us to lots of great ways to think about writing. And one of the things she introduced, which was a bit of an aha moment for me, was doing peer reviews in our class. And it was really interesting because I always read a lot as a child and I think I had a natural knack for writing when I was that age. And certainly I found out that I had a knack for analyzing something and understanding how it how could be better.

Amy: And that's the critique process, right?

Laura: Yeah, exactly.

Amy: It’s about giving and receiving feedback. It's powerful.

Laura: It really is. And I think I was able to do that in a way that made everybody feel good. You know, like, oh, let's make this good together kind of thing. And so I started to think, oh, this is really fun. I think this is a job. (Laughs) But I thought it was like, well, I should be an editor. Maybe I could be an editor at a publishing company or something like that. So when I went to college, I started doing English as a major because I thought this is the path.

Amy: Okay.

Laura: But there was a lot of Shakespeare requirements. I feel like there was a Shakespeare one, two, three, four, five, six, perhaps classes that I needed to take. (Laughs) And I was like, okay, I'm not going to do that. (Laughter) I went to a new program, which was kind of a friend of mine called it dilettante studies. But essentially a basic liberal arts program. And one of the requirements was to take a language. And I knew how to speak French fairly well, so I decided to learn Spanish and I loved it. And it became a super fun way to just start to navigate other cultures and able to think about the history of different places and literature of different places. And it was really exciting for me to kind of think about this. [0.20.00] And when I finished school, I started what I thought would be an editor type stepping stone at… like an imprint of a publisher, which ended up being quite a demoralizing job. And so I ended up quitting that and went to Nicaragua to teach English and live with a family and do a bunch of stuff there that would hopefully expand my mind and horizons and make me think about other things I might want to do, including maybe teaching English, I don't know, or learning to incorporate Spanish more in what I was doing.

Amy: Did it?

Laura: It did. I had another aha moment. (Laughs) And it was actually back to art because there was so much great public art and iconography and really cool stuff that had to do with what was happening politically at the time that was just really moving, really interesting and public. And I had this thought of like, oh, this is super cool. This notion of art and expression in these in the public realm like that was super cool. And I started to get interested in artists who are more like conceptual artists who are doing the same kind of thing. So like Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer .

Amy: Artists that are using words, though.

Laura: Yes.

Amy: It's still very important here, yeah.

Laura: Yeah, exactly. There was another artist who did maybe less public work, but also had that kind of word image thing that I found very inspiring, which was Lorna Simpson. But just like people who are thinking about things conceptually, and it was not necessarily about crafting a beautiful painting, but it was like thinking about the world we live in and society and sharing experiences. I thought that was awesome.

Amy: And uniting around a kind of message and codifying it into symbolism and iconography that we can interpret just from taking it in, just from, you know, seeing it. I just totally concur with you. I've also just felt that artists who use words as a sculptural medium or as a conceptual medium, it's so fascinating to me because there's such an entry point that you get to get in and sort of mix around with the words in a way that helps you come up with completely new contextual information, completely new perspectives and ideas.

Laura: Yeah, I agree. And the other thing that is interesting is that when you start to think about the media or the medium that they're using, whether it's digital or it's carved in a stone or it's like a wheat paste thing, that also has an impact on the way you receive the message.

Amy: Yeah, it was delivery.

Laura: That was a huge aha moment. I was like, oh, this is very, very interesting.

Amy: So when you went back to art school and studied sculpture, right?So is this at a graduate level? Are you doing another undergrad?

Laura: I did another undergrad because I really felt like I needed that foundation. I didn't feel like I was ready for something that was a kind of graduate degree. I wanted more.

Amy: Yeah. I did the same. I get it.

Laura: Yeah.

Amy: Totally. I found something that just opened up my horizons and I'm like, but I don't know how to do this. I need to start from the beginning. Okay, so art school and you're doing large scale installations and covered in concrete and just really getting into it. And did you find your people? Do you find like a sense of self that was allowed to explode?

Laura: I definitely found my people. I loved it. It was a great place. I went to Halifax to a school, NSCAD. It's Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. It's kind of known for its conceptual art take. And so there were so many people who were also doing either second degrees or slightly older, not 17, in our 20s. And it was a great community. And I made very close friends and ended up forming a band with some of the people that I met there, which was kind of a side thing that was very unexpected. [0.25.00]

Amy: Okay. Well, I'm so glad you brought it up because if you didn't, I was going to. So we're going to unpack this a bit, because I need to know more about it. You were the bassist in this band.

Laura: Yeah.

Amy: First of all, just tell me how it got formed. And also tell me when you first picked up a bass. Was music something that you came to the school with some knowledge of?

Laura: Yeah. I played guitar when I was a teenager. So I knew how to play guitar. I did actually a lot of classical guitar when I was younger, so I had some basics. And we started as a bit of a bigger group, and I also knew how to play piano, so I was on the sort of piano keyboard thing. And as our group kind of tightened up and we became... the group's name is actually an acronym of four of us in the group, which is... It's called JALE, Jennifer, Allison, Laura, and Eve, which happily we had a couple of As and Es in there, vowels are very important in this kind of acronym world. (Laughter)

Amy: Already an all-girl band in the 90s, this is pretty badass. I'm very, very excited.

Laura: We had friends who were doing music. And it just was in the air a little bit. Really active music culture. Friends were playing bands. We went to see music all the time. We just started to do stuff at open mic nights. And then started to write our own songs. And there was a lot of local indie labels and we did a single and all sorts of... It just kind of snowballed in a very quick, organic, but quick way. And we suddenly got played on the national radio station here, CBC. And I remember running through the halls in art school, getting Eve out of her class and going, oh, my god, we're on the radio right now. (Laughs)

Amy: Wow, that's so fun! So I was involved in a similar scene. I don't have the gift of playing music or singing. I mean I sing all the time, but not professionally. But I was involved in a similar scene. All my friends were in bands. And so everything that you're describing about playing open mic nights or indie bars or even just... When you're in art school, there's this incredibly sort of gooey community where everyone's kind of supporting each other's work. And so these pop-ups happen, warehouses, it's very DIY, and so it's really scrappy and so avant-garde in that every type of music is supported. And you really have complete freedom to find your voice. I was out in the crowd, but there's this whole group of people that comes out to support it, so it feels like a very nourished kind of scene. But it also feels like it's the weeds. It's not the cultivated rose garden, right? It's the weeds that are growing up in space. And the early 90s was a time when that could all happen. There were a lot of reasons that those conditions were in place. But it was really kind of a glorious time for music, I think. And I'm so excited to hear that you found some fellow travelers to join together and do this thing.

Laura: Yeah, I love the way you're describing the weeds. It really was. People did anything and everything, and yeah, you're right, people use the word ‘community,’ it really was a community. You would be there to support people. Where was your scene?

Amy: San Diego.

Laura: Okay, yeah.

Amy: Because those scenes were all kind of like they were traveling around. And you got played on the radio, which is kind of an important pivotal moment, because it is this moment of validation. You probably had been played on college radio a bunch of times.

Laura: That's right.

Amy: College radio is great. But that's also like it's not real until you're played on mainstream radio. [0.30.00] And when that happens, then you start to give it more credence in your life. Like maybe this is a thing I should quit thinking of as a side thing and put more energy into it. Is that what happened for you?

Laura: That is exactly what happened. And probably this happened in San Diego as well. But the music industry was really interested in what's the next Seattle. So what's the next…

Amy: Yes, that was absolutely happening in San Diego.

Laura: Yeah. So you had record executives coming to our sleepy little town and ordering things like lattes and people would be going, I don't know what that is. That kind of thing. (Laughs) And we actually ended up signing to a label, which was Sub Pop, which was part of the Seattle scene.

Amy: Yes, so you were signed in ‘94 or ‘93

Laura: ‘93, yeah.

Amy: Getting signed to Sub Pop is like getting signed to the majors of weed culture. It's like getting the ultimate validation but not selling out.

Laura: Yeah. There was a lot of cred involved.

Amy: So much cred. So much cred. (Laughter) And there were all these other major labels and their indie imprints that were all out feverishly looking for the next Seattle. But Sub Pop was the one.

Laura: Sub Pop was the one, we were super lucky. We were so lucky. We got to do albums, record albums. We went to Chicago. We toured North America. We toured Europe. We toured the UK. We had bottles of beer and cigarettes thrown at us. It was the full experience. (Laughs)

Amy: I'm really curious, as we look at your whole creative trajectory, this is a big monumental deal. It's like being a child star or something. Like it can't not be foundational to your creative life, being in this band, having this experience, and being signed to Sub Pop at a time when being signed to Sub Pop…so in ‘93, Kurt Cobain was still alive.

Laura: That's right, yeah.

Amy: So you were there while it was all sort of exploding and imploding and reinventing itself, which is huge.

Laura: It was huge. And it was also a time when there were a lot of musicians, like a few sort of all-female bands also kind of finding a bit more voice and place, which was also really exciting. And that was interesting. I mean people would often throw us onto the same night as, you know, two other all-female bands, even if our sounds were totally different.

Amy: Right.

Laura: But it was cool that they were out there doing that and we were out there doing that, and, yeah, that was another big part of the excitement, I think, for us.

Amy: Well, I heard you describe yourself as a feminist art student, and so that would be a huge way, like to be able to use your art to scream it into the audience where people are ready to hear it and digest it. That can feel like a very potent way to communicate your art and your feminism. But not just through your art, like through your vibe and your attitude so this is what I wanted to get at, touring is such an intense test of endurance and scrappiness and intra- and inter-band relations. But it's also you really getting comfortable in your own skin in a performance capacity and figuring out what connects with the audience and figuring out how to read the audience. So that very keen attunement, but then also collaborating in real time like an improv troupe. Tell me about that because that just sounds orgasmic, honestly. [0.35.00] (Laughter)

Laura: Yeah, I mean, I think especially when I think about recording together with the band, that was when it was really exciting. Like, that's when you're like, you do that part, oh, what if you do that, oh, what if you do that, oh, that's so cool. And the other part of that kind of… collaborative swirl that was super exciting. Lots of breaking down your ego, trying to push back up your ego. It can hurt, but it can also feel fantastic especially as you learn how to write songs, how to collaborate on somebody else's song and not ruin the vibe that they're trying to go for. How do you step onto something and make it better as opposed to..

Amy: Oh, this is the peer reviews.

Laura: Yeah, peer reviews, exactly. (Laughs) So that was lovely. And for me personally, I had a hard time writing songs right away. The other three in the band were great immediately somehow. They knew how to craft a song. They knew what they wanted to talk about. They knew all those things, so I was a bit of a late bloomer. And I think my songs were a little bit different in terms of melody. But when you have a band where everybody's writing songs, it's also kind of interesting because everybody's got a little nuance that is about their own perspective, and yet it needs to be part of a kind of holistic thing that we do together.

Amy: Yeah. I mean you probably had a really good feel for that because as a third sister, you were kind of part of a band growing up.

Laura: Yeah.

Amy: So you've described yourself as an introvert at times. What was it like to have to turn yourself on for an audience and really give them a show?

Laura: It was hard for me, We weren't real sort of rock and roll show people. (Laughs) We were a little bit more chill. I mean happily for us, the kind of ‘shoegazer’ movement was happening where people would just look at their shoes while they played. But when you do it every day for six weeks, after a while, it just is easy, and it's so nice to kind of break into that moment where you just get on the stage. But it's hard coming cold.

Amy: Yeah, I imagine.

Laura: But it's easier once you're doing it. Where you survive a few mess-ups or things that go wrong or whatever, and you're still there, and you're still playing a show the next night, and you know what, it's all going to be fine.

Amy: I hope you had a lot of support. From the stories that I've heard, it can also just be this rapid succession of victories and heartbreaks. I mean, maybe you have a really good sold-out show one night, and then the next night you play Lawrence, Kansas, but a bigger band is playing two doors down, and nobody's at your show and it can just be so disheartening, and you have to learn to work with yourself and the moods of all the people that you're with through these really epic highs and lows.

Laura: Yeah, that's absolutely true. And I would say sometimes people really like what you're doing, and sometimes they don't.

Amy: And sometimes they show up to hate-watch. (Laughter)

Laura: Well, especially when people would put these kind of headliner and an opening band together. Sometimes it's done really well, and sometimes, again, it's back to the, oh, they're female, and they're female, so let's put them together. And we had an experience in London. We were playing at a huge theater, and we were opening up for a band that was really popular, L7. I don't know if you remember them from the day?

Amy: I do. I do not care for L7. (Laughter)

Laura: Well, you would have been in the minority of the audience that night. We were very different from them.

Amy: Yes, you are. I listened. I watched your music videos and I listened…

Laura: Oh, did you? Oh, no.

Amy: Nobody should put those two bands on the same bill. [0.40.00]

Laura: Anyway, we did get a little bit of boos, we did get beer bottles thrown at us. We did get stuff like that that happened. And then in the press the next day, there's a pretty active press in the UK, and I think it was… one of the big music presses reviewed our show and talked about how we dressed like schoolteachers. And that was like a moment where we were like, what? We wore jeans and shirts and sneakers, and I don't know, maybe this was... also UK was a bit more flashier, a bit more music glamour. And we were decidedly anti-glamour. It was part of our thing. So that was a hard trip, generally.

Amy: I bet, but it's also so culturally eye-opening, right? To kind of understand those nuances. Like, oh, this is an audience that's more comfortable with a little more glam or a little more production value or however you want to put it.

Laura: Exactly.

Amy: Thank you for sharing all of that, because I think it's a pretty intense boot camp for creativity, honestly, because there are so many moving parts, and so much of you has to, I don't know, live through everything in a pretty fast pace, all of these highs and lows. But then you're also watching all of the other bands that you're in community with, right, that you're friends with. You're watching them mature and get somewhere or mature and decide to leave band life, or you're watching some people not be able to handle it and burning out. Others are experiencing the excruciating pain of fading away and having to let go of something that they're not ready to let go of. It's just such an incredible chapter to be able to own in both emotional life and your creative life that it got you kind of trained to be a creative leader. Does that resonate with you?

Laura: That does. Yeah, totally. Yes. I agree. I think you just said boot camp, it was kind of like that. You learned so much so fast and putting yourself out there in a way that you need to be fearless.

Amy: And empathizing with all of the things that can happen both through you and vicariously through your compatriots, you’re in it. You are in it. But one of the other things that was kind of delightful to witness from my perspective was so many of these musicians and creatives were also the in-house designer for their bands in a very DIY way, needed to design their own merch and flyers and album art. And in some ways, that became a bridge to what they might do or a very solid bridge to graphic design after the band life maybe was no longer viable or no longer desirable.

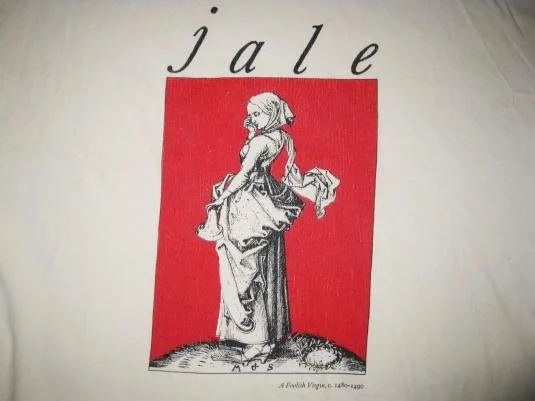

Laura: Yeah. Totally, that is exactly the path. And one of the things, we were talking about feminism too, for us, it was really great, not only could you talk about certain things in your songs, but there were certain codes that you could play with visually that were really fun to play with. So not necessarily being very nail-on-the-head kind of messaging, but just taking something and making it a question mark. For some reason, we had these shirts for a while. It was an old woodcut, and the title of it was The Foolish Virgin. This became a shirt that we all produced and created. So just little things like that that you could play with. For me, that was a big moment where I was like, oh, you can tell stories in design. I didn't really understand that before. [0.45.00] But suddenly, it's like, oh, okay, yeah, all these things that we're making or telling a story, even before you hear the music, there's something going on there that people are receiving. And that made it really interesting to me suddenly.

Amy: It's very similar to the symbology and iconography that you were talking about in Nicaragua. It has to code feminist. It has to code indie or whatever. It has to code not only indie, but it has to differentiate you from all the other female bands that they're trying to lump you together with.

Laura: Yeah.

Amy: You had said that initially design didn't appeal to you because you thought it was just about making things pretty and palatable. And I think a lot of people had that impression of design and still do. I mean, we're in the bubble now. We know the power of design. But the general culture, I think, is still confused and thinks it is just about making things pretty.

Laura: Yeah.

Amy: This is kind of a branding question. But if you were to give design a rebrand so that people could understand it for its full spectrum of power in terms of being a process that you can deploy your creative agency to have impact on the world, the world that isn't yet, like the yet-to-be-built world.

Laura: Yeah.

Amy: What kind of thought experiment would you do about rebranding design with a capital D?

Laura: It's a great question. I think that's a question I think about all the time as I try to talk to clients about how their worlds might change should we work together. I think people try to do that with design thinking. That term became a little bit of like, it's not just trying to make something nice looking. It's about making change. And I know that term has gone in and out of style and started to mean something maybe a little bit different than I don't know, the initial way that people were talking about it. But I do feel like the idea of thinking and strategy is really important in design, and it doesn't get enough airtime. So I guess throwing that word ‘thinking’ in is helpful, but the strategic piece of design, like why do you make these choices? Why do you, even if you're working on something that is really visual, the impact will be felt across the organization in different ways. But it's like being able to talk to people about, like it is a strategic process, and I think that's where people lose the plot.

Amy: As you were talking, one thing that came to mind, and it's come to mind before, but it just showed itself pretty powerfully to me, is design, sometimes I think of it like a cockpit or a mixing board, but it's the process of dialing in all of these different things from message and materiality and the conditions that you're operating in to the audience that you want to meet to, to how much emotional resonance, how much personal expression, how much craft. You know, all of these things, and dialing it in to produce the outcome, knowing that if you change one little thing, it'll change the outcome. So iterating along the way, like the mixing board just really feels like an apt metaphor for me. I wonder if that lands for you.

Laura: Absolutely, and we talk about that sometimes too, actually. I bring in music references constantly, and we do talk about, you know, it's like if you have a tuner and you go too far, and you get static, and you want to find that sweet spot right there where everything is really clear. Or this notion, sometimes we talk about a baseline and riffs, and being able to kind of have… this is our typical way that we show up, and then you're allowed to riff, you're allowed to kind of go off, as long as you come back, and you've got this kind of drum beat of consistency underneath. [0.50.00] So yeah, musical metaphors definitely make their way into my language. But I think the mixing board is right. It is complex. There are a lot of things going on, and there is a moment when you get it right, and you're like, yes, this is it, and that's when it's keen. And you're right, suddenly somebody might, over here, do something totally different, and you're like, oh no, now it's totally wrong. Get back, come back, come back. (Laughter)

Amy: So after JALE, you worked your way through the book world in graphic design, and now you've been at Bruce Mau Design as the chief creative officer for, I don't know how long you've been CCO, but you've been at Bruce Mau for, you've logged several years there, and worked your way to this position of leadership, which is, I mean it's probably a little bit more like record exec than bass player, I'm assuming. There's some similarities and some differences. I'm sure there's talent scouting and marketing of a novel creative idea, a sound you haven't heard before, we’ve got to figure out how they're… you know, but I wonder if you can maybe describe the work you're doing now, and because I'm just so fascinated with the music background, if you can sort of highlight the similarities and differences that you see.

Laura: Yeah, I mean now I'm in the work a little bit, and I'm also doing a lot of things that you were talking about, like thinking about hiring, thinking about clients and the first conversations that we have with clients, and setting the tone and that kind of thing. But when I'm working with the teams, it's really like, from a musical perspective, it's almost like the producer, I suppose, who's at the mixing board and kind of helping. Because people will have their great ideas, and they'll bring them to the table, and my job is to kind of like maybe fit these ideas together, or to take one idea and put it somewhere else, but to kind of give it more shape. And you know, throw in an idea here and there. Did you ever see Eno, the documentary about Brian Eno?

Amy: I've interviewed Gary Hustwit, he was a San Diego music friend.

Laura: Oh, amazing.

Amy: I mean he wasn't a musician, but he was in that whole scene. He was a publisher. So I haven't seen the movie yet, though.

Laura: Well, I guess you see a different one every time.

Amy: Yes.

Laura: We won’t have seen the same one. But one of the things that I saw, I loved it, I loved the notion of it always being a different movie, this kind of remixing. So cool. And I loved hearing from Brian Eno. And one of the things he talked about when he was working with David Bowie was like he wasn't exactly the producer, he didn't play any instruments. But what was his role, and it was, I think they said something like it was to keep possibility alive. I think that's what David Bowie said. And I love that idea. I mean I think I do more than keep possibility alive. But I think it's a really important thing that it allows for more experimentation.

Amy: Yeah.

Laura: And it's kind of like knowing when to start to, close it down and make it into a thing. And when do you keep it just kind of experimental and still playing with ideas and that kind of thing. So that's another aspect of my job, I guess, is to…

Amy: Keeping possibility alive.

Laura: That's right.

Amy: To “yes and”, until it grows into something so big that it just needs to be sort of fine-tuned and into some shape.

Laura: Yeah.

Amy: I mean I just think about when seeds are pushing up through the earth and they're growing, when their ideas and projects are like this too, there's a stage where they're just so helpless and not really viable yet. And they're so easy to kill at that point if somebody starts to talk about how it's impractical or how are we going to do that? And they start to think about all the difficulties, so keeping possibility alive until it can become viable is essential. But we don't talk about that enough. We don't talk about in school or especially in the corporate environment where everybody's got to pitch in with their expertise about why it can't work, right? [0.55.00]

Laura: Yeah.

Amy: The keeping possibility alive is this really fragile essential stage, So thank you for putting words to that.

Laura: Well, we can thank David Bowie maybe.

Amy: David Bowie and Brian Eno, but also thank you for your service in doing that.

Laura: Well, I definitely learned that from Bruce Mau, I would say. He was somebody who, when I worked with him, he was really good at letting things kind of morph and change and you were never really done. I mean I've had experience of being in a cab with him, driving to the Oprah Winfrey Network and changing a presentation in the cab to, you know, like he's just sort of like that kind of quick, okay, I think possibility should die now, you know, these moments. But I definitely... (Laughter)

Amy: Possibility should, like, hold.

Laura: Yeah, exactly, maybe not die, it's a bit dramatic. It was something that I definitely felt it was important. But you're right, there are all these pressures, time, money, etc., that are working against that notion. But they're realities, so you have to sort of figure out how to do it within the constraints that you have.

Amy: Yeah. The whole, I don't hear a single.

Laura: Exactly. (Laughter)

Amy: Okay, so I have a very real question that I'm dying to ask you. It's a little personal, but it's a little professional. I'm thinking about the feminist art student who's still alive and thriving inside you. And in what ways is she empowered and allowed to thrive with all of the power and resources that come with being a CCO? And in what ways is she still fighting the fight and rebelling against the status quo?

Laura: Amy, you are very good at very pointed questions that kind of get to the heart of things very quickly. (Laughs) I think I'm very aware of whose voice is being heard. And I'm saying that, and I know that I can always do better. I try to be really aware of that. I try to give young designers platform, encourage people who are… or maybe you see them feeling a bit constrained. You want to help open things up for them a little bit. So that's kind of within the team. I've found that working with other female leaders is really exciting and interesting, and I learn a lot from that as well. We just did some work for the National Ballet of Canada, who has a really incredible female leader. And just watching her and her decisiveness, it's very exciting. And it's sort of… just sort of drink it in. We just did work for this gallery with another leader who also has a kind of momentum and force that is also amazing to watch. And I think I just appreciate some of those things as well, and the way certain women lead in ways that maybe are different than I might expect. And it's exciting. I find it very exciting. And I hope that I also expose team members to that as well. Like there are all these interesting women doing these really interesting things. In terms of fighting the good fight, sometimes I feel like in certain situations, your voice is just disregarded a little bit. I mean, I've had situations where I've walked into a room and people assume I'm just there to take notes, or just these kinds of things that happen every now and then that you see and they're infuriating. [1.00.00] But you just kind of carry on and vow to never work with that person again. (Laughs) But also talk about it within the team.

Amy: That's got to be a weird thing for a junior team member to see someone else sort of automatically invalidating you. And then you then have to model how to navigate that situation.

Laura: Yes, it's true. And being open, I think, about it is important. So we had a moment where we were giving a software lunch and learn kind of thing. And the team that was showing us some stuff, they were just kind of creating something. For example, you could do this or you could do that. And they were using a young, attractive female and then making her dance suggestively… maybe not suggestively, but it was just a little bit like, why do that? You don't need to do that. We all love cute puppies. (Laughter) It could be anything. It could have been anything. But it was that. I didn't say anything in the meeting, but I did kind of follow up afterwards. And then I kind of let my team know that I did that just so that they would feel like they could do that too in their own circumstances. You're allowed to call something if it makes you uncomfortable. So I guess a little bit of that. Trying to share the battle maybe a little bit.

Amy: It sounds like modeling it as well. It's so tricky too, because calling it out in the moment sometimes creates more discomfort for everyone involved. So you have to make a game time call on how am I going to handle this? But if you just bring it up afterwards and your team doesn't know about it, then they don't know that you had their back or that you acknowledge this and that you were willing to go out on a limb to acknowledge its inappropriateness or how it could have been better. And yeah, so much of it is being able to see someone take those actions. And it doesn't have to be a big war or a battle. It just has to be a willingness to take the actions and let it be seen so that it can be learned. And set a culture of it's okay to do this. The culture piece is probably the most important piece.

Laura: Yes, and I hope that... you never know whether it does empower people to do it or not. Hopefully they don't have those situations that they're encountering.

Amy: Yeah, but you can't go home at night and have a glass of wine and sleep soundly knowing that you didn't do what you needed to do.

Laura: Yeah, that's right.

Amy: So then you can't show up the next day with your full self. If you abandoned yourself the day before.

Laura: Totally right.

Amy: You're cool, Laura Stein!

Laura: You're cool, Amy. (Laughter)

Amy: Where are you taking all of this? What do you hope for, and this can be personal, this can be professional, this can be design general? But where are you putting your energy, power, and creative agency? In what direction?

Laura: I've been doing more design talks and that kind of thing recently. And I really enjoy it because I love the analytical piece. I love to kind of bring a new idea together. I like understanding why we're doing things and kind of just reflecting, having that impetus to reflect. And so I'm going to try and keep doing that and invite other people to kind of do that as well and try to find moments to collaborate with people on that kind of thing. I find sometimes it's nice to be a lonely person in your room thinking your thoughts. But it's also really great to have somebody to just kind of build something together with. So that's what I'd like to keep working on

Amy: Yeah, that sounds like you're forming a new band. (Laughter)

Laura: Maybe so.

Amy: You know, maybe not exactly the same kind.

Laura: Well, Amy, I did notice that your name does start with an A. [1.05.00]

Amy: Oh, so I can be a vowel. (Laughter) I can be a vowel in your all-female band, I’m totally in. (Laughter)

Laura: The LAs! (Laughter)

Amy: This has been an absolute delight. Thank you so much, Laura.

Laura: Thank you, Amy. I've loved the conversation. I love listening to your show.

Amy: Hey, thanks so much for listening. For a transcript of this episode, and more about Laura including links, and images - head to our website - cleverpodcast.com. While you’re there, sign-up for our free substack newsletter - which includes news, announcements and a bonus q&a from our guests. We love to hear from you on LinkedIn and Instagram- you can find us @cleverpodcast and you can find me @amydevers. If you like Clever, there are a number of ways you can support us: - share Clever with your friends, leave us a 5 star rating, or a kind review, support our sponsors, and hit the follow or subscribe button in your podcast app so that our new episodes will turn up in your feed. Clever is hosted & produced by me, Amy Devers with editing by Mark Zurawinski, production assistance from Ilana Nevins and Anouchka Stephan and music by El Ten Eleven.

Nun’s Island, where Laura spent her early childhood.

jale playing

jale band photo

jale, foolish virgin

Sonos work by Bruce Mau Design

Brickline Greenway work by Bruce Mau Design

National Balley of Canada work by bRUCE mAU deSIGN

INFINITI work by Bruce Mau Design

Clever is produced and hosted by Amy Devers with editing by Mark Zurawinski, production assistance from Ilana Nevins and Anouchka Stephan, and music by El Ten Eleven.