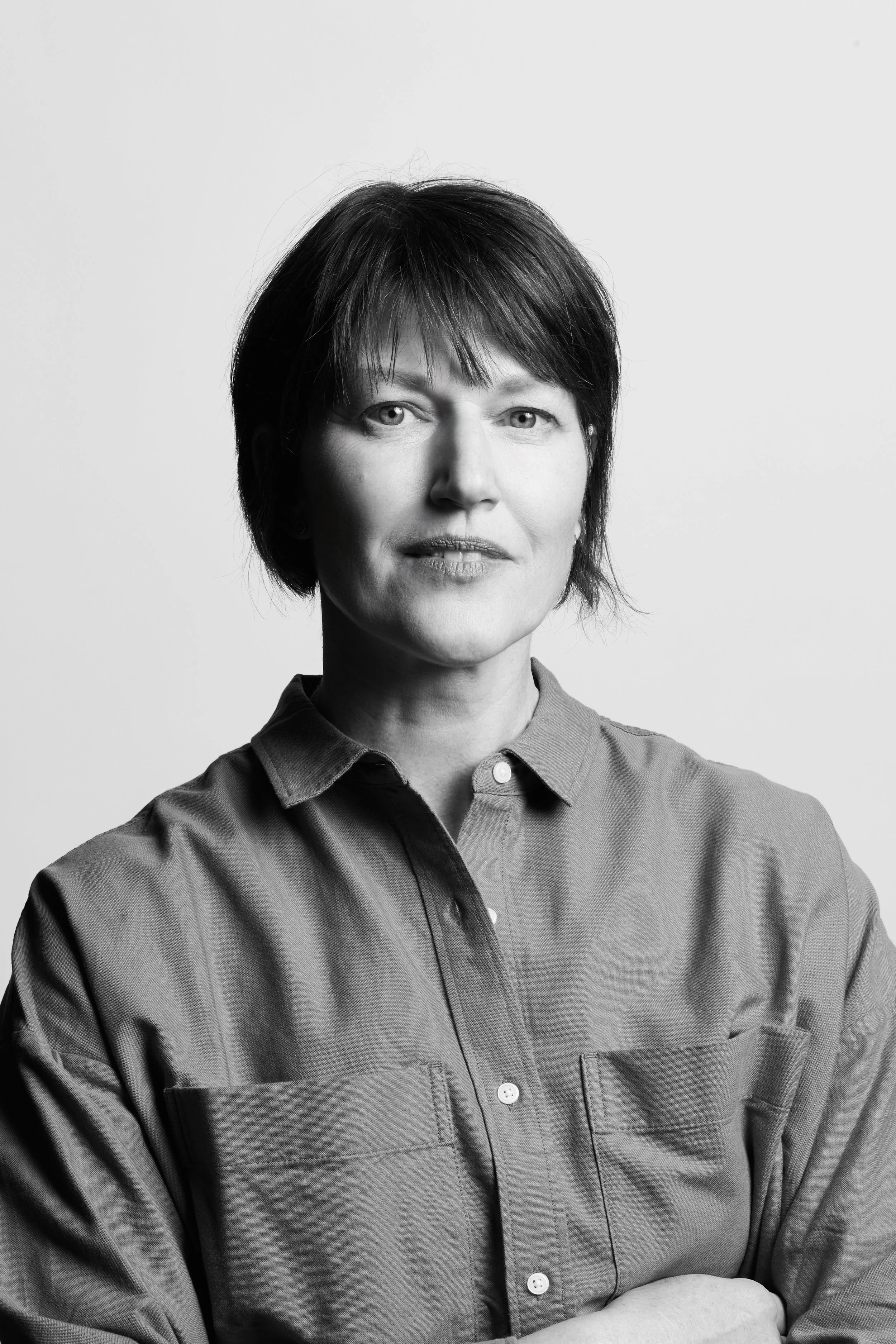

Ep. 232: Studio O’s Liz Ogbu on Spatial Justice and the Role of Design in Healing Grief

Designer Liz Ogbu grew up in Oakland as the daughter of Nigerian immigrants, but it wasn’t until her first trip to Nigeria at 16 that she grasped the profound role place, family, and cultural context play in shaping who we are—and what we create. Drawn to the creative possibilities of architecture, she studied both architecture and engineering before traveling across Africa on a Watson Fellowship, an experience that sharpened her understanding of who her work is ultimately for: the people most impacted by design.

Today, Liz is catalyzing what design can do—in transforming informal marketplaces, helping communities heal after being fractured by freeways, and weaving practices of grief, accountability, and repair into the built environment. Her work transcends traditional architecture, centering the excavation of harm and the pursuit of more empathetic, community-rooted design at a moment when it’s needed more than ever.

Subscribe our our Substack to read more about Liz.

Learn more about Liz on Linkedin and her website.

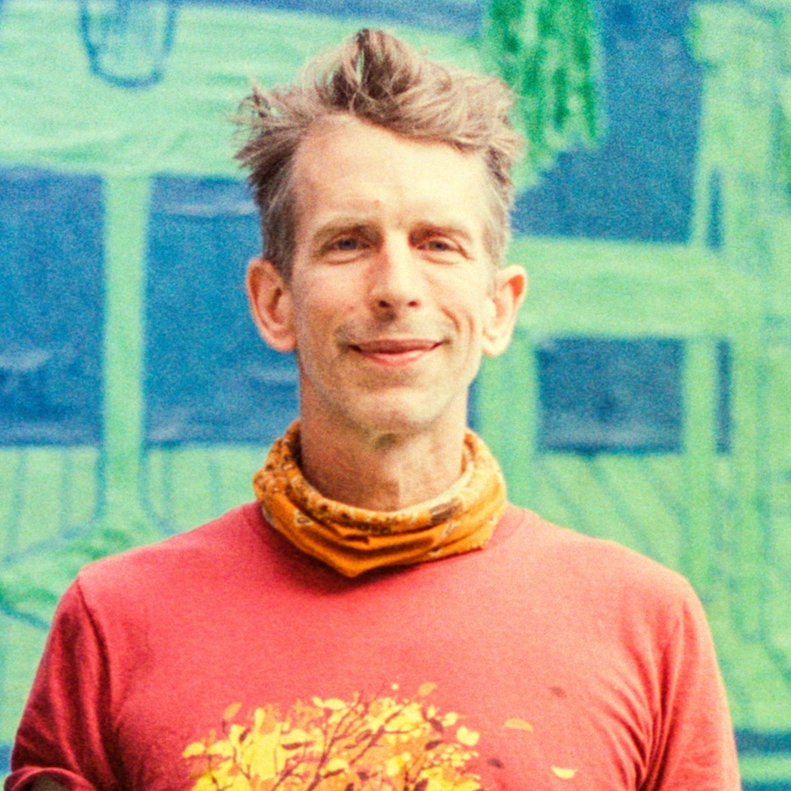

Amy: Hi everyone, I’m Amy Devers and this is Clever. Today I’m talking to Liz Ogbu, a designer, spatial justice activist and community grief worker. She is Founder + Principal of Studio O, a multidisciplinary innovation studio that focuses on work with and in communities with vulnerable populations to create high impact models that can yield deep and sustained social benefit. Trained as an architect, with an undergrad degree from Wellesley and a Masters of Architecture from Harvard, Liz served as a Design Director at Public Architecture, a national nonprofit that mobilizes designers to create positive social change before founding Studio O, in 2012. Liz has a long track record of working with historically marginalized communities to leverage the power of design to catalyze community healing and foster environments that support people’s capacity to thrive. Her work blends a combination of community-centered research; dynamic forms of engagement and prototyping; equitable architecture and planning strategies; place-based grieving and repair frameworks; and tools to build participatory power and community-centered systems. Her leadership in this area has been recognized many times over with prestigious honors and fellowships, and her TED and TEDx Talks, which share a creative practice and life rooted in community wisdom and healing, have been viewed well over a million times. As you’ll hear, Liz’s commitment to this work is unflagging, rigorous, and delivered with a buoyant spirit and infectious enthusiasm that just propagates light and hope… it’s wonderful! Here’s Liz…

Liz: My name is Liz Bu and I work in Oakland, California on unceded Ohlone land. And I am a designer, spatial justice activist and community grief worker. And I do it because I'm really committed to healing people's relationship with the land and healing their relationship with the places that they call home and making sure that those places support people to thrive.

Amy: That is important, powerful, and much needed work. And I would love to learn how you came to this by kind of retracing your steps. Like would you be willing to tell me about your formative years and growing up in Oakland? I understand your parents are immigrants of Nigeria, so if you can put some color and brushstrokes to that picture, I'd love to hear all about it.

Liz: Yeah. So both of my parents are immigrants. my dad came in the mid sixties, my mom in the seventies. They come from small villages in southeastern Nigeria. I and my three younger siblings were born here. I have an older [00:02:00] half-sister who was born in Nigeria, and I was born and raised in Oakland, which sometimes these days feels like a rarity to find somebody who has that.

But you know, I think I always had a strong presence of the Nigerian culture as I was growing up. And that was, I kind of was like one foot there, one foot here. I didn't go back until I was 16 for the first time. But I think for me, growing up with parents who were immigrants, it really helped me understand, you know, that there was a greater sense of the world beyond the place in which I lived.

Amy: Right.

Liz: And so being able to say that there was, there was more to where I was from and to what made me, I think really helped kind of cement this idea that the [00:03:00] world is big and often meaning that we're weaving in different cultures, different histories, different modes of understanding. And that really has impacted the way in which I moved through the world.

Amy: I believe it. I mean, to have such strong ties to the world in terms of having, um, a root system in Oakland and a root system in Nigeria, that must have felt like, like a kind of access in a way. Did it? I think it probably was for me, not until I got to college that I learned how to connect the dots or see that broader perspective as an asset. I think as a kid I was just trying to, I knew it, but I was just trying to figure things out. And add all the pieces together.The appreciation of what it meant was probably something that came as I became an older teenager. Moving into young adulthood,

Liz: All that I experienced was sort of the like immigrant [00:05:00] community here in the Bay Area, and then it wasn't until I was 16 that I got to actually go back to my parents' villages and, and understand that must have the culture from that perspective.

Amy: Yeah. That must've been impactful though. I mean, being a teenager and making that trek. Tell me about that.

Liz: Yeah, you know, I don't know that my parents actually gave us that much to prep for, like what to experience. So it was definitely, you know, I was, I was 16, so, it was my first time out of the US I had no idea what to expect.

Amy: Wow.

Liz: And um, you know, we also happened to arrive right after a coup had hit the country. So there was also some political instability. Also didn't know what to expect around that. Um, but then it was like really amazing to go when we flew into, um, the eastern part of the country, which is where [00:06:00] my parents are from, and to just be greeted by hordes of, of family that I had never met.

You know, up until that point I'd only met a couple of people who had come to visit. But you know, I have a rather large family on both sides extended families. And so to meet them and to get this sense of this other part of me was a really amazing experience to see the places where my parents were from, to learn a little bit more about their histories from when,before I knew them as parents.

And I would say for the work that I do, it made it really interesting and sort of being there and being immersed in that context helped me understand, [00:07:00] um, you know, my roots and this idea that our tendrils extend to both the place that we're calling home currently, but also the places that either we called home in the past or that members of our community or our family called home

And whenever we show up, we're bringing all of that to the table. And so it's part of why I'm always really interested in understanding. Where people are from and how they came to be where I am meeting them. Because I think it provides a lot in terms of giving a sense of the whole self as opposed to just what might be standing right here in this present moment that like, actually we're a sum of everything that came before us.

Amy: Yes.

Liz: And so to connect to somebody to understand the work to do, it's really important to connect at that deeper level.

Amy: I a hundred percent agree, and that's one of the reasons why I'm so interested in learning about the depth of your experience, but, and, and your connections. [00:08:00] But I, I also just think of it like, if you could bring the prequel and the sequel together in with the present film, then you have like you have the backstory, you have a understanding of the arc, and you can engage with somebody without accidentally being too reductive.

I'm Interested in what dinner conversations might have been like in the home. Your parents were social scientists, and you've described yourself as the weird kid who liked to draw. So what did that sound like in your house?

Liz: My dad was a professor of anthropology at uc, Berkeley, and, and taught there for over 30 years.

And my mom is a public health expert and, so I think growing up, you know, we had the normal conversations that families have, I think we always did talk about people, um, and, and how they came to be who they were.

My dad would often have professor friends come over. Mm-hmm. And we'd talk about different plaes, um, around, around the world really and, and what people were like in those communities. And, you know, hearing my mom and the work she was doing in San Francisco and different neighborhoods and the people that she was encountering.

So I think without knowing it, I would say that they almost gave me this early education about people and place that I probably wouldn't have been able to name so eloquently at the age of eight, right? Eight or nine. [00:10:00] But I think probably landed as little tendrils that, you know, kind of found a place in my, my mind and in my system to get supplemented to the work that I later did when I started to find my way into architecture.

Amy: Yeah, I would guess so. I mean, anthropology and, and health are all part of what you're doing now.

Liz: Yeah, and and it's interesting because, I've been teaching since early in my career at the university level and for a number of years, the courses that I would teach would often bring in readings in anthropology, sociology, public health as a way to sort of say that like as architects, we're often taught to look at a space and analyze it. But we're not necessarily taught how to look at a people and analyze how they're relating to that space.

And so much of how they relate to that space has everything to do with [00:11:00] what gets covered in these other disciplines, that are about like how people come together as communities, how their histories impact the ways in which they showed up.

And so for me to be able to articulate or see a complete story of a place, I had to understand the people that inhabited that place. And so those early conversations are just the ways in which I think my parents' work landed within me was this idea of the more I can do to understand the people, the better it enables me to understand the place.

Amy: That makes a lot of sense. I mean, what is a place without the people? it's so abstract to think that we could build systems and structures and infrastructure with, without a full comprehension or holistic view of how the people, it will impact the [00:12:00] people.

But back to you, you chose to study architecture first it was gonna be engineering. But then you found your way to architecture. I mean, based on the work that you're doing now, this seems like this was a really great decision but what can you talk to me about arriving at that decision and what it felt like in school to kind of be proactive about claiming your own creative agency and finding your perspective?

Liz: Yeah. I mean, I think engineering for me, I loved to make things I always have since I was a little girl. And so, uh, engineering kind of seemed the natural place to go with that. But in some ways, architecture, it also been intimately a part like the making that goes into engineering also relates really well to the making that goes into architecture.

And, funny story that I I'd kind of forgotten for many years until I was just relating it to somebody a few months ago, is when we were making that first trip back to Nigeria, we needed a house to stay in and we were going to build one in my father's family's compound. And asthe kid in the family who drew my parents were like, great, you can draw the house. So I drew the plans working off of plan books to be clear, but I drew the plans for the house. And it's still up, has shown some wear and tear for being 30 years old. But it's where we stay when we go back.

Amy: So wait, so wait one might save a 15 or 16-year-old, you designed the house that you still stay in when you go back to Nigeria.

Liz: Yes.

Amy: Wow. I'm gonna need to see pictures of that.

Liz: Yeah, [00:14:00] We just went back, I just went back with my family for first time in about a decade and took pictures 'cause I realized I didn't have any pictures. And the story comes up as a humorous anecdote every now and then. And I'm like, oh yeah, I guess I should take pictures of this thing that I drew at that age. Um, but even then, I, I don't know that I thought architecture. I still was thinking engineering. And I went to Wellesley for college and taking some of the initial coursework for engineering I just found I didn't like it, didn't do well was really struggling. And I've gotta figure something else out. And, um, I, I thought of architecture as one option, but you know, I kind of cast the net wide. I took an architecture studio at MIT because Wellesley has a companion program where you can take classes there and Wellesley itself didn't have any architecture studios and [00:15:00] so I fell in love with it. I loved it. It sparked my creative juices, the ones that you know from, as I said, from a little kid, I would always make things. I made my own own life-sized dolls when I was a little girl. And so this idea that I could

Amy: What? Out of paper?

Liz: Out of paper.

Amy: Still, okay. Did they have characters and backstories and wardrobes?

Liz: No. No. I would also like make my own little books and yeah, I just like to make things and I like to push the envelope of the things that I could make. And it was like, Ooh, I could try this. but they did have little I would use Ziploc bags and put behind their throat so that they could eat, they could sit and eat and you could put some stuff in. So

Amy: this is you caring for them. Oh my God.

Liz: Oh. So, you know, clearly I, at a young age, I was trying to figure out how to make things work and [00:16:00] how to Yes. Have to, how to have my dolls be full participants in my experience.

Amy: Well, yes. And how to care for a nurture

Liz: They couldn't drink anything because that didn't work with paper, but, architecture was great because it, it nurtured both, like just being wildly creative and coming up with things, and then also making things. And what I didn't realize at the, at the time was that I was super fortunate because I was at Wellesley.

There was an architecture major, but they called it at the time, and I think they still do an interdepartmental major. So there wasn't an architecture department, there was like a list of courses that you could take both at Wellesley and MIT and you could also petition for other things to, to count towards the major that weren't on the list.

And so what that did is it kind of created this choose your own [00:17:00] adventure approach that I could actually design the major around the things that made me really interesting. So I could take architecture studios at MIT, I could take sudio art at Wellesley and then and architectural history at Wellesley.

And then also I could petition for courses like Urban Economics and Urban Sociology, which bring in that other piece that I was interested in and felt like mattered but weren't on the like typical course list for the degree. But I could come and say, I want this to count. I think I even petitioned at one point for an English course that was about the city and we were just reading texts that dealt with the city and I said, Hey, can this count towards the major? And they said, yes. And so it gave me this really broad approach to what architecture was, which I didn't realize was actually quite unusual, but for me, fit in really well with how I saw things.

Amy: I'm so happy you had that and I'm so happy you jumped in and [00:21:00] participated with full vim and vigor. It sounds like, from Wellesley, you went to Harvard. Did you go directly? Did you have any time in between.

Liz: No, fortunately I had a couple classmates who went directly and I saw that architecture school was really grueling and that I needed some space between doing that. And I had never gone abroad when I was at Wellesley, in part 'cause I played basketball and our season was not conducive to traveling abroad. and so I, you know, had this wanderlust. And so I applied for a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship and ended up getting it.It's from the Watson Foundation, which, uh, has its roots in the Watson family that founded IBM. And, uh, the [00:22:00] way the lore goes is that Thomas Watson Jr. was not necessarily the most business-minded initially as a young man. And he ended up joining the Merchant Marines and traveling the world for a year or more and found it was tremendously beneficial to him and his maturity.

And when he came back and came into the company, he was the one who took IBM from typewriters to computers.

Amy: Oh, shit. That's a nice story.

Liz: And so he felt that like more, um, more people needed to see more young people in particular needed to see the world and that, um, that would be hugely beneficial for [00:23:00] like what they could do with their lives. Wellesley was one of the participating ones and I had this idea of.

You know, the things I was learning and studying in my architectural history classes, um, they included cities and places that weren't like Nigeria. And the, I was still struck by the stuff that I had seen in Nigeria and wondering like, well, how do I think about that as I think about this career or path that I've chosen?

So I proposed to spend [00:24:00] a year in Sub-Saharan Africa, understanding architecture and understanding urbanism in particular and how people engaged with the architecture. And so originally the plan was to spend it in three countries, Ghana, Ethiopia, and South Africa, and do apprenticeships. And then, you know, it, this fellowship is known as like stuff happens and, you know, you just figure it out on the fly.

And so by the end, I ended up visiting 12 countries Oh, wow. Doing apprenticeships and some, but mostly research and traveling and documenting and interviewing people. So that’s what I did for the year after college.

Amy: That, that sounds like 12 or 15 years of education kind of compacted into one, just through being there and observing and embedding and, and asking all the questions that you did.[00:25:00]

What an eyeopener. how were you changed when you came back?

Liz: So this was in 98, 99, it was pre-Google. You know, I'm with my Lonely Planet book. Which, for the record had quite a bit of misinformation in Africa, it makes you grow up really quickly 'cause you have to figure things out on the fly. I was a woman traveling by myself, so

Amy: it was also sharpens your survival skills.

Liz: But actually I found a lot of people took care of me. that it actually, it was sort of the generosity of people was really evident of like, introducing me to places, introducing me to people, making sure that I had some support whenever I landed in the next place. But it [00:26:00] also, you know, I got to Ethiopia at the time that there was a conflict with Eritrea and so had to leave, or the first woman that I apprenticed with in Ghana who is this amazing architect, Alero Olympia, who's now passed. She got really sick with cancer while I was there and I had to pivot, to do some other work.

And so it was like a, a lot of life lessons kind of came up. And then I landed in South Africa, kind of on the tail end of Mandela's presidency. And so there were a lot of interesting questions about what was gonna happen in the country and they were still feel in the shadow of apartheid. And so it was just this front row look at all of these different countries that honestly had not really been part of my orbit growing up, and I would probably say were not part of a lot of people's orbits growing up.

Liz: And in particular for the work and the path that I ended up doing, a lot of [00:27:00] my interest was like in informal economies, so markets, squatter settlements, etc, and how those places were being constructed and what was being done for people who lived in those areas, and how in many ways they were making a way out of no way.

Amy: Mm-hmm.

Liz: And, you know, architecture at the time largely kind of abandoned them to like figure it out, right? The architects were working on government buildings and things were expats and, and, and rich folks and wasn't necessarily at the time tending to those who lived on the margins. And so what I became really interested in is like, well, what would it mean to actually work with those at the margins?

And I think that really deepened for me as a commitment and as an interest over that year. and. So then I, I was able to take it and, and I have this weird now specialization in African urbanization [00:28:00] and a apartheid architecture and, and things like that that, you know, come in handy when I'm teaching courses.

But also, I still I've been fortunate over my career, I've been able to do some more work in, various countries within Africa. And, and I think a lot of it was because of the seeds that were planted during that year where it felt really comfortable to be there. And then also having visited so many countries, I think sometimes we have a tendency to lump Africa into this like, giant bucket.

Maybe we might distinguish between Sub-Saharan and, You know, above the Sahara. But, uh, I think all the countries, even those that are adjacent to one another are actually, while there are similarities and overlaps, there are also very distinct cultures, very distinct political histories and social structures and so for me, being able to kind of visit many countries and be able to think [00:29:00] about things that were similar or what were the conditions that led to places of difference, also really just supported the work that I do in my career. Right? Like that I've been to a ton of different places. I've insights about a ton of different places, but I also really appreciate the individual specificity that comes from the place where I'm working in.

And so it is both being able to understand what is unique to a place, but also like what kind of wisdom may be able to come from some place else or that you can take from that place to another place. And so that interweaving that happens within my work in large part, got a huge boost from this year that I spent kind of hopscotching around that continent and, and trying to understand all these different places.

Amy: So now you are an architect and a healer and you operate at the intersection [00:34:00] of spatial and racial justice. and you've done so many meaningful projects. When you were talking about the informal economies, the project that came to my mind was the day labor station.

I wonder if they informed each other. but I also wonder if you can pull out a few examples of, of your work and help us understand spatial justice through, uh, you know, illustrating some of these projects.

Liz: Yeah. Uh, I can give a quick snippet on the day labor station to start. So that was a project that, um, was started in, um, the early two thousands at Public Architecture, which was the design nonprofit, uh, that sadly is no longer in existence, but was based in San Francisco and founded by John Peterson. And this was a project that was started before I came to the, to the [00:35:00] practice, but it was one that I kind of took on. And the idea was looking at day labor hiring sites, um, you know, the Home Depot parking lots, the gas station, sometimes by the building supply store. and you know, when you think about informal sites for people who are not familiar with like, informality, those sites are like textbook definitions of informal sites, right? Like the Home Depot parking lot was not designed for people to go and seek labor in it. but makes perfect sense, right? I think one of the things about informality is it's often born a very rational and intelligent thinking.

If somebody's going to go and get supplies to build something, in all likelihood they might need some help building it, right? So if you position yourself there, it's a great place to both meet that demand and also [00:36:00] meet your need. And so when we started this project in the early to mid two thousands, and so at these sites, there was no access to shelter, toilets, water, et cetera. People are, you know, if you go by, you often see that the, the workers are just standing out in the sun. Um, and at the time that we were really working in earnest around this was not long before there was a big immigration debate in 2007.

Um, and so these sites became somewhat controversial. If you were mad about immigration at the time and you couldn't go down to the border, you could go to your local hiring site. And so there was this tension that was springing up. And we, we went to the workers as our clients. And for me that like was an early lesson and, [00:38:00] and definition of client where I call clients, not the people, not just the people who pay me, um, but the people who are impacted by the work.

And I think our, that's the way the system normally works, is that privilege is the first, and it kind of doesn't make room for the second.

Amy: I've heard you repeat this definition of client in the research, and I love this and I'm gonna repeat it to my students because we're not doing any favors if we're just building the things that the people who pay us want us to build. Like if we're not serving the people who are impacted by it, then we're creating all kinds of harm without even understanding what we're doing

Liz :A hundred percent. and I think the thing to note is that because the system privileges the client who pays, there's not a lot that's been set up to create space for the client who is the person impacted to be able to come to the table [00:39:00] and give their take on things, right? So a lot of the process you see in many of my projects involve creating ways beyond just doing community meetings, which I know is like often as architects we're fond of doing as a way to get to that client. But I find community meetings can often be quite transactional. And if you really want to get the information to know what is needed, both those that like may come to your own mind, but also beyond that stuff that you don't even know because you don't know the life of the people who will ultimately inhabit the place.

And so for me it's about like, how do we step into like conversation and more than conversation, how do we build relationships with the people who are going to live with what you've created? And so with that project, we did a lot of work of going to day labor hiring sites. And I often joke that, you know, it was never like a day laborer was gonna walk in into the office and say, we have a problem at the corner, we could use your help.

Right. So it was often us going to them. [00:40:00] Right. And when we talked to them, a lot of what they would say is like, um, to them, their hiring sites were sacred. That was where they sought work to support themselves and their families. I remember one, um, or in Houston who said that no one sees people just see the parking lot or the roadside. That sacredness is invisible to people beyond, um, the workers themselves.

Amy: Oh, wow. That's kind of a powerful understanding.

Liz: Yeah. And so, you know, we designed a prototype shelter that could, you know, sort of just met all their different needs, and wasn't just about a place to get hired, but we also saw that a lot of groups, um, uh, immigration support groups were also doing things like, providing ESL training and I can convert to a classroom, et cetera. Um, and, uh, the unfortunate part of it was the timing. Uh, we came up with that project right around the time that, um, like. Just before the 2008 economic collapse. And so at the time although like kind of talked to a lot of different cities about implementing it, when the economic collapse hit.You know, if you're cutting school budgets, it was hard to then justify putting money towards this thing. but for me it was a fascinating project in the sense that like, you know, we did a lot of other stuff not just designing it, but there was also a huge advocacy p piece that was a part of it that people can see if they go to the website and it was kind of understanding that part of the role was not just [00:42:00] the design of the thing itself, but like leveraging design to also open up a conversation about what does it mean to treat people with dignity And to see folks not as this like faceless group of people, but actually as carpenters, welders, you know, skilled craftspeople.

And just like restore the humanity. And I, I would say that in a lot of my projects, you know, whether it's, uh, a redevelopment of a affordable, uh, section eight housing into a mixed income neighborhood with zero displacement or transforming the site of a former highway that displaced the black neighborhood in the seventies, a huge orienting thing at the start of the project is how do we restore a sense of dignity and humanity to those who are impacted by the harm and [00:43:00] support them to be at the center of what we understand healing to be. And that sometimes that's about a, like literal physical design. Sometimes it's about advocacy. Sometimes it was about tossing in grief processes. Sometimes it's an oral history project. Sometimes it's some combination of all that. But I think this idea of being able to heal people's relationship with the land kind of actually also relies on healing people's relationship with each other. And some of that is restoring the sense of dignity and humanity and creating a way that we connect at that level so that we can then understand what it means to create a healing place.

Amy: How? I mean, I'm fascinated and I, I don't wanna use more words than necessary, but I mean, when you, when you start talking about restoring a sense of dignity and helping people kind of heal their relationship with the land... What are some of the actual mechanics of that? You've talked about how you build relationships, but like how, how do you actually build the relationships? It must take so much attunement, like so much real human attunement.

Liz: Yeah. I think it's, for one, it's coming in as a human being, which sounds weird and quaint, but like, if I had followed the path of architecture, I think as it was like sort of originally taught to me, it often is this, you know, frames kind of the engaging with communities in this very transactional lens.

It's this thing we have to do to move things forward. And for me. Especially because sitting in this realm of spatial justice, I'm often walking into situations where there has been considerable amount of spatial harm. And it means there's a place [00:45:00] where there is broken trust, where there's a lot of grief. And so if I approach from a transactional place, what's gonna happen is people are gonna be very defensive because what they still remember is what happened to them in the first place.

Amy: Yeah.

Liz: And you will not create a successful project, at least that meets the aims that I think could make success Amy: right. And so it's like coming in with the intent to create relationships. Right? Like for me it's always, it's like the highest compliment. If after talking to someone, they're like, oh my God, that was amazing. When are you coming back? You know, I remember being like deeply touched in the pandemic. Where I had like some community members checking in to make sure I was okay. Somebody sent me a mask. People check in about my family. I check in about their families. Right? Like, we know what's going on. [00:46:00] And, and that's because what we've built is a relationship. Like not a transactional, set of agreements. So that's the starter. Like I come in with a relationship when there has been spatial harm, I think sometimes there's a tendency to not want to. Belabor the point, right? We don't wanna focus on the bad stuff.

We wanna hop and talk about the good thing that we're gonna create, but actually that harm is now part of somebody's story. So the other piece of it is, if you're walking into context where there has been harm and, and you have, when you're building a relationship, you have to do the work to get to know people and earn their trust so that they will share how that harm has impacted them. And then you have to acknowledge the harm.

Amy: Yes.

Liz: Right? Because you're acknowledging the fullness of their story. And that is critical to building trust. Because if I were to go in and say, yeah, that if highway came through, but now we're moving on to better things, or that power plant was here for 90 years, but now we're gonna replace it. And so like, let's not worry about all the 70 to a hundred years that you've dealt with this thing, let's, let's move on. Right. That move on is a signal that you're gonna dismiss their needs and interests.

Amy: Well, it's also a signal that I don't have or want to have the capacity to hold the harm that's been [00:48:00] caused by you. I'm not accountable for it. And so I'm not gonna demonstrate to you that I fully understand it because I don't think that's necessary and I'm just gonna do this other thing that I think is necessary and try to get buy-in from you for it.

Liz: yeah, and And I wanna also say, I think the majority of the people who are working on the like kind of architecture, municipal, like the implementer side are super well intentioned. I just think we're all shit at dealing with grief and harm.

Amy: Yes, yes.

Liz: And it's very uncomfortable and we don't understand how to do it in the process. So I also wanna say like. For the many times I have seen the kind of bulldozer thing, it's often done from a place of good intention and lack of capacity to deal with the hard piece.

Amy: Yes. So I think the essence of what I'm hearing you say is that actually dealing with the hard piece is essential, and [00:49:00] as is processing any kind of trauma, like it has to be able to be witnessed and named. And if you're going to trust somebody to build something that doesn't cause more harm, you have to trust that they understand the nature of the harm that's been caused already or else they don't know how to not repeat it.

Liz: Right. Like the assumption is that they will repeat it. And the assumption is like, how can I, for my own protection, if I can't trust you, go out on a limb for you. It's for me, that trust building, actually this recognition and acknowledgement of that harm and holding space for it is very important because I think oftentimes when projects go that deal with these contentious places go awry, it's because the harm has not been tended to. And so it's never like it [00:50:00] disappears, it just goes underground and then comes up in some other way. Mm-hmm. And also as someone who's deeply committed to wanting to create places that feel healing and that support communities to thrive. I'm not living up to that mission if I'm not truly understanding what it is that we need to, to heal. If I treat it as just like textbook design problem, it's like you can't design a solution if you don't know what the problem is that you're designing the solution to. And so excavating the harm is partly like helping me understand what exactly are we trying to design a solution to.

Amy: Excavating the harm sounds like really tender, sensitive, important and powerful work. And I, you know, in some of your projects, some of that has been through oral histories. [00:51:00] there was a three-part grief primer. Can you talk to us about the creative practice of excavating harm and healing and grief and holding grief?

Liz: Yeah. So that the three part grief primer that you mentioned was connected with a project into Akron, Ohio. So there's a highway called the Inner Belt, was built in the seventies or started getting built in the seventies.

Um, you know, it had a number of years for which construction was active and it displaced a vibrant black neighborhood and close to a thousand families and businesses and social cultural institutions. And then, in 2016, the state decommissioned a portion of the highway, basically permanently closed it, the northern end.

And in [00:52:00] 2020 I was hired by the city of Akron to lead a community visioning process. What I found was that in the 50 years since the highway had been built, there hadn't been a lot of like conversation about the neighborhood that preceded it, even within the black community. And, from what I've already talked about in terms of my process, I knew that the client, you know, the client is like the whole city of Akron, but the like core client in that is like the people who were displaced and their descendants.

And so in going and seeking them out, what I found is like, they hadn't even talked about it because it was just too painful, right? They stopped sharing the stories, they buried them just because it was easier to do that than feel the grief of what they had lost. And so. We did the work to sort of build the relationship for them to start to trust us.

[00:53:00] But one of the things that I found as I was starting to do the research was like, it was actually really hard to find out what that neighborhood had been like. Right? And actually to understand what the problem is, you have to understand what was lost. And I couldn't understand what was lost if there wasn't a lot of information. And so that's what led to oral histories is something I've used in the past because in getting people to tell their stories, it's a way both to show that you honor what has been there

But also for me, there's a Brene Brown quote that says, stories are data with a soul. And so for me, When I listen to stories, I'm actually getting data about what that neighborhood was like, what pe the grief is. Yes, I know people are feeling grief, but to see [00:54:00] the profoundness of the grief actually relied on me seeing the depth of what they lost.

And that's what the stories helped convey. I could go to a general community meeting and talk about what was lost, but it's much more impactful if I could get Emery and her voice to share what was lost. Right. Without having to like trod Emery on this road show to constantly go and share her story.

And I think one of the things I heard from a lot of the elders, um, 'cause many of those who were displaced, their elders now, if they were kids when the displacement happened. They're like, I don't want people to forget. Right? Like when I'm no longer here, I don't want people to forget.

I want my grandchild, I want my great-grandchild. I want the kids [00:55:00] growing up to know what happened. So we partnered with the public library, and they have like a great amazing digital archive. And so we basically digitized all the stories. We edited them down so they sound like StoryCorp clips.

So if you're a researcher you could get access to the full audio, but for everybody else, we kind of created these clips and then we recognized for like, I know when I've played it for some elders, they start crying 'cause they're so moved by it. And so we knew there was a lot of grief also in hearing the stories, and so that's where the grief prime came out of, to sort of say the goal here is not to run from the grief or hide from the grief,, but to acknowledge it's it that is here too. And it's part of what we wanna hold, but we want you to listen to the stories. We want the stories of this neighborhood to come back to life because if we can all collectively hold the stories, then we can all also collectively hold what healing might need to look like.[00:56:00]

Amy: Wow. There's a idea that grief is cleansing, on a personal level, but I'm very moved by the idea of collect collective grief and sort of cleansing and healing a whole community by just being willing to acknowledge it, not run from it. And actually, you know, use your creative agency to put some, some systems in place that can support it.

Liz: Yeah. And to be clear, like the, that work we're still, we're at right now talking about what it might mean to like, support people moving through the grief process. But, for me I harp on acknowledgement, because sometimeslike that step is not even done. And so there are many more steps in [00:57:00] grief healing.

But like, if we could just get to the place where we all take the space to acknowledge, like it moves us so much further than where we've been. And I would argue that some of the, the craziness that we see in the country and in the world right now has a lot to do with the lack of space of acknowledging and holding space for our grief.

Amy: I a hundred percent agree.

Liz: I think the tension we have right now is we exist in a, a world in which a lot of the professions are in some ways caught by their, like, old structures.

Amy: Yeah. Right.

Liz: For which this kind of stuff was not part of it. But I think that the. The energy and frankly just the collapse that is happening and the speed at which the collapse is happening is kind of creating a situation where you kind of ignore addressing it at your peril.

Amy: In your corner of the architecture industry, is it expanding? Do you feel like this is a wave [01:00:00] or is this still like a niche that requires a lot of work to create more awareness around it?

Liz: So I would say I think spatial justice has been expanding, like I think a lot, I see a lot more, I describe it as kind of akin to what happened with the sustainability movement, right? Like I think there were some folks who were interested in it, who would do it, and clients that kind of met us there. And then a growing demand from the client side that then kind of has led to more firms taking it on.

I think also the like generations that have been coming up recently in school have also come in and also been providing demand on that side as well for these kind of things.

Amy: Yeah. So it's exponential.

Liz: So yeah, so it's been growing. I think healing is coming online, but it's been a slower turn. But I think right now we're in this like really interesting place where I think people are seeing the need, but we're also in a climate where [01:02:00] some of that stuff is getting pillared. Right. Like that, uh, there's, there's definitely a huge there backlash that's happening right now. And we're still in the like early days of the backlash. So it's sort of unclear to me how it's going to pan out in terms of affecting the industry. But I will say, you know, I sort of felt this when the 2008 crash hit. And, within architecture we had what I describe tongue in cheek, which is probably not the best tone, but, um, you know, in times of chaos it's good to keep a good sense of humor.

But we had the culling in architecture, Right. Like a 30% cut in jobs in 2008, because the economy collapsed. Right? People coming outta school couldn't get jobs. Firms were massive layoffs. People just [01:03:00] left the field entirely. And, during that time I was working at public architecture and I didn't fear for my job because we were busier than ever. Clients could not always figure out how to pay for us. But the work, this idea of work that is geared at a social impact and helping people in need like that was needed more than ever. Right? Like, so that's kind of what created the, the demand. And so I say that now to almost just say like, what we're seeing with some of the just like the collapse, the cruelty, the depravity that is happening out in the streets right now, that is actually intensifying. So like the things around spatial justice and healing are needed more than ever.

Amy: Yeah.

Liz: But for some it may not [01:04:00] feel safe to do it or it may feel like there's not the space in the work to do it. But for me, I remain committed. 'cause it's, and I, and I think the clients that are showing up to do the work are the ones that are like, let's go. Right? We know this is needed more than ever. And so for me, I've always had a commitment, um, or I shouldn't say always, but for me, a lot of the, at least of this time in which the practice of Studio O has been in existence, has been really committed towards creating models because I recognize that since I've been in the work long enough, I can pick and choose the projects.

And oftentimes people don't wanna be the first for a variety of very good reasons. And knowing or seeing examples of something that has been done before, and being able to point and say, see, they did it this way, so we can try it, right? Mm-hmm. Or, I want it do to project like this was done over here in Akron, right?

Um, so I continue to show up and kind of trying to push the edges now, even if there's like forces that are coming in that are trying to dissuade from talking about justice issues, talking about inequity, um, because I recognize that like we need models to know that we can still do this work, that the need is still here and we can still show up, um, and, and do the work to heal places, heal communities, heal people.

Amy: When you talk about that, I see it in your face, like your commitment is really, really evident. And, this is kind of a personal question. I can imagine that at times it's really difficult to be able to listen to grief story after grief story. How do you care for yourself while you're making such a intentional effort to care for others?

Liz: Yeah. Uh, as an immigrant child, I was very used to working hard and not taking care of myself for a long time. So I would say I am on the recovery path to being better about that. yeah, and, and also recognizing if I burn out, then I'm no good to anyone. So I've tried to improve the way in which I tend to my own care.

Um, I have friends and family that are also very good at nudging me around that. So like making sure I'm taking time off and, and checking in with myself, meditating, having a therapist

Amy: Yes, good.

Liz: All of those things. and then I would also say the other thing [01:07:00] is I think particularly if you're people are interested in getting into grief work, like actually a huge component of being able to show up in that work is doing my own personal grief work.

So like I've been in an active practice for a number of years of like kind of tending to my grief and healing my own grief stuff. And, right now I'm in a two year collective trauma course 'cause I'm partly a masochist. And so it's, it's fascinating and it's amazing, and also like the whole ethos of it is like, y'all have to heal your own trauma to be able to support the holding of space around collective trauma.

So a lot of the work we do is like connecting with our historical trauma and healing it, which, again, does not sound like the kind of thing that most people would do for fun. but for me [01:08:00] it's, I can feel like, oh yeah, the more I tend to my grief, the more I tend to my trauma, the better I can show up whole for somebody else who does not necessarily have those supports.

So the idea is not, I'm trying to come in and be a savior. I'm not trying to come in and be people's therapist, but I can't hold space for others if I can't hold space for myself. So it's having an intentional practice to make sure I'm doing that.

Amy: Thank you for sharing that. I really appreciate it. I also wonder if the act of actually excavating your own trauma and putting yourself through the modalities of healing is a kind of training of sorts, so that when you are talking to somebody else about their grief or trauma, you can say, look what, here's what [01:09:00] worked for me, or here's how. Is that coming in, in some ways?

Liz: It's in a way, right? Like I, so I rarely will say, here's what worked for me. But when I see ways in which my trauma shows up, right? Mm-hmm. It makes me think, oh, there's a characteristic of trauma, or Here's a question connected to trauma and grief that I can ask, right? Like, so if I can see, oh, there's a grief moment that's connected to this thing that happened when I was a kid, right?

Like that I didn't put much store in. But I can then see the effects of like the age in which it happened. Then when I go and talk to this [01:10:00] person in this community over here, and I know that their grief that we're trying to support is a historic grief, then there are certain questions I can ask based on an understanding Oh, when grief hits you at certain ages, these are kind of the, the qualities that come up. Right. And I may offer up of like, oh, you know, I have found meditating and taking a breath really useful for me. You know, when I was doing the Akron project in like two years into the project was when, um, there was that horrific police shooting of Jalen Walker and he was killed.

Oh. And so we had to have a, our advisory group meeting a few weeks after it happened. And you know, there was definitely the agenda of the things we needed to do to keep on schedule with the project. But I also was like, [01:11:00] people are grieving. Right? I can't come in here and say like, so we're gonna do this, this, and this today, because that's what's essential to keep the project moving. Right?

Amy: Right.

Liz: And I knew that from when I have experienced grief, things that have been helpful for me, it's just having someone like hold space for witnessing it, and acknowledging it and helping me with like breathing through it.

Amy: Mm-hmm.

Liz: And then giving me space to just share what was on my heart. And then I also find like words like poetry super useful. So in that, you know, session, I basically was like, and we have people from all different walks of life on that group. And I was like, today we're just gonna hold space for this. We're gonna give everybody a moment. I took them through a meditation and then gave everybody a place to share, [01:12:00] reminded them to take breaths at different places, and then ended with some words.

And, you know, for a lot of people it was super helpful and it actually led to a deeper bonding of our group because they were also able to see each other in where they were standing in their grief. And so, again, yeah, it's all stuff I've learned from doing my work from all the trainings I've done, but it's less about the telling and more about showing through, actually setting up an experience that allows people to move through it and, and to choose, right? Like if you didn't wanna engage in the thing, you were also welcome to pass and not say anything. But, you know, I think that's where it comes through, but it's a thing when I say I do these trainings or participate in these things, it's not that I'm taking notes [01:13:00] to then do the, to the steps.

Actually the, the value of it is in feeling it experientially so that I can also understand how to support somebody else to go through it experientially. And, and that's when I talk about like. How do we think about things being relational and not transactional enough and be like everybody knows how to hold a relationship because likely you have at least one relationship in your life.

So think through the experience of what it was like to build that relationship, what it's like to tend to that relationship. Then you know actually how to do it with community members. You're doing the exact same thing. So so much of the learning, I think is just like, how do we move through it in a more embodied experience?

Amy: Thank you for painting that vivid picture, and I felt like you took me through the experience a bit too. It's like really helpful to be able to wrap my head around what you mean about like [01:14:00] lived experience is what helps you create the conditions to help, uh, create a space for an embodied reaction.

I'm so mincing my words right now, because I'm kind of like, choked up a little bit and I, and I'm just wondering like, I really also wanna know from your perspective, what do you think that it's important to say or to share about you or your, your story? Like what do people not ask you that you wish that they would so that you could put it out there?

Liz: Wow. Okay. I will say like, I think this has been interesting to talk about sort of my childhood and, and cultural upbringing, right? Because I think those things are inherently part of what you get when I'm showing up to you, but maybe aren't things that are covered as much as some of the other stuff.

And, you know, I, I have a dream that, we get beyond this collapse and get into a time where everybody's grief is acknowledged. like we reckon with the things that are hard and that have been broken and the past and the harm that has been caused. And we create places where every single body gets the right to heal and [01:16:00] thrive. And so that's the world I'm working towards and I hope it's the one that others want to join in doing as well.

Amy: I am gonna sob after this is over. I love that. And I love that you, you, and then you can say that and then Chuck like, have a big body laugh. It's so, it's so good. You're such a full spectrum human. Like you're, you're capacity to,

Liz: I should say I just came from a week long trauma training, so I have already balled my eyes out for the past week. And then like, so you're feeling the lightness, like to the aggravation of trying to make it home in the middle of mercury retrograde combined with governance shut down. So like, I have gone through the gamut of human emotions in the last seven of the days. So I think that's also, you're getting me in the, like, I've done the cycle.

Amy: Okay, well you're wonderful. [01:17:00] You're just absolutely wonderful and I love your dream. I wanna put all the good vibes and updraft under your dream that I can, because that's the dream we should all have.

And I'm just so grateful for the work that you're doing. It's really good work. It's not just the work that you're doing, but you’re cataloging it and chronicling it and creating, guides and resources. Your website is so helpful for anyone who might wanna learn more about this.

It's, I, I just love it because. It's doing the work that you're, thank you. It's, it's helping you do the work, right? If people can kind of research on their own time asynchronously and they, you don't have to repeat yourself over and over, over again.

Liz: And, I never wanna be the only one. Right? My goal is like that there's armies of us ready to do this work. And I know when I was [01:18:00] coming up, like bless the heart of every single person who I pestered and then they talked to me, but like, it was really hard to find information about how to do this and it felt like somewhat isolating 'cause I couldn't find for the longest time other people.

And then I finally found my people. But, I just realized like a lot of folks want to do the work or want to be able to prove that it could be done differently. And so yes, if I have the privilege to be able to. Set. Like I, it's a privilege that I can choose my own projects and, and, and push the envelope.

And to use that privilege appropriately, it's to open the door so others can do this project. And that this project in Akron is not the only one that like used grief as a process to think through how to reimagine that space. So yeah.

Amy: Amen. Hallelujah. More power to you. I just, I've just really, this has been a personally enriching conversation. I've just enjoyed it so much. [01:19:00] And I'm so deeply, deeply grateful that I get to turn around and share this with an audience of listeners. Thank you so much, Liz.

Liz: Oh, thank you for asking to share the story and, and, and the questions and bringing the energy that you brought.

Day Labor Station Community Garden from Public Architecture

Reviewing Old Neighborhood Maps with Studio O.

IntentionalShift Performance, Feline Finesse. Photo Credit: Amani Wade

Clever is produced and hosted by Amy Devers with editing by Mark Zurawinski, production assistance from Ilana Nevins and Anouchka Stephan, and music by El Ten Eleven.