Ep. 235: Secret Mall Apartment’s Michael Townsend on Ephemeral Art with Enduring Impact

Public artist Michael Townsend grew up in a military family that relocated often—at least ten times during his childhood. He learned early how to explore new locales and seek out new friends before moving on to the next temporary hometown. His final relocation was to study art at RISD, when he chose Providence as home—and began quietly reshaping it. He founded the Tape Art movement in 1989 and built a thriving practice rooted in ephemeral public murals, deeply private underground installations, and highly clandestine collaborations, including the now-legendary Secret Mall Apartment.

For more than 30 years, he has created hundreds of temporary murals and collaborative public works around the world, including the 9/11 Hope Project and the invention of the BOOM! Projector. Now, with the success of the Secret Mall Apartment documentary on Netflix, it’s clear that he and his collaborators were deeply intentional about incubating that narrative until it was ready to be heard.

Moving fluidly in and out of the shadows—showing up, making an impression, then dissolving underground only to emerge again—turns out Michael himself may be a work of ephemeral art.

Subscribe to our substack to learn more about Michael.

Learn more about Michael and Tape Art on their website, Instagram, and Youtube.

Amy Devers: Hi everyone, I’m Amy Devers and this is Clever. Today I’m talking to public artist Michael Townsend. Okay — before we go any further — have you seen Secret Mall Apartment yet? It’s the independent documentary currently topping the charts on Netflix, about eight Rhode Island artists who built a fully functioning secret apartment inside a shopping mall in the early 2000s… and lived there undetected for four years! It is wild. And it is deeply, deeply uplifting.

The film, artfully directed by Jeremy Workman using footage the artists themselves captured at the time, follows Michael and his collaborators as they build the apartment while simultaneously planning and orchestrating large-scale guerrilla art operations. It’s got heist movie vibes, but rather than theft, they are navigating high-risk situations with tactical precision, strategy, and artistry to carry out beautiful acts of public care and social commentary.

On the surface, it’s a story about sneaking into unused space and pulling off an audacious creative feat. But underneath, it’s about trust. Collaboration. Creative agency. Gentrification. And the quiet, strategic resistance of asking: who is public space really for? Michael’s art practice involves drawing with tape, having founded the Tape Art movement more than 30 years ago, he’s still going strong, creating large-scale ephemeral public murals and leading collaborative drawing workshops in psychiatric facilities, hospitals, and schools, in collaboration with his art partner Leah Smith, — it’s work that centers participation, presence, and trust. His artwork lives in public space, but Michael himself moves fluidly in the gray areas — between permission and transgression, visibility and concealment. - from non-destructive guerrilla art intended to deliver care to a grieving public, to deeply personal installations that operate underground, literally and metaphorically. As you’ll hear… tape is Michael’s primary physical medium, though he is equally intentional about working with the intangible energies of: narrative, trust, care, and ephemerality itself. His particular magic lies in creating work that is designed to disappear physically… but endure culturally, Here’s Michael.

Michael Townsend: My name is Michael Townsend. I am a public artist here in Providence, Rhode Island, and the primary through line of my work is ephemeral artwork, and my career has been rooted in tape art, which is the art form of putting tape on walls in a collaborative method to make large temporary murals.

Amy: Well I want to get right into it and usually what I like to do is start by going back to the very earth, the soil that you were grown in. Talking about early childhood formative years, can you tell me about your hometown, your family dynamic, and your youthful fascinations?

Michael: I was brought up in a military family, and the reason that's of note is that meant that we traveled quite a bit. Both my parents were brought up in the military also. They both went to 14 schools before they attended college, so they traveled a lot. Both of their parents, so my grandparents, also in the military, their parents also in the military.

Amy: So there's a generational itinerancy that you're comfortable with.

Michael: Yes, my brother and I were the first ones to not go into the military. (Laughs) We probably moved, I think 10 times before I left the household, you know, to go to college. So enough moves to sort of see the entire nation. I was born in California. I lived in a couple places in California, a couple of places in Texas. We lived in Missouri when I was in middle school, came to New England. We were on the military base in Newport when I was in kindergarten. And then primarily my parents settled in Massachusetts, Central Mass, right outside of Worcester in a town called Holden. And what's nice about moving is that it gives you the skill of being very comfortable wherever you go. And so there are a lot of ‘army brats,’ as we loosely call it, who are really adept at sort of being dropped into spaces and making friends quickly and being like, oh, this is where I belong and I will integrate myself into these communities. I came to Providence as a college student to attend school here. And in a very real way, that became the moment where I got to sort of choose where I was from. And so I've been in Providence, and I sort of very much think of myself as a Rhode Islander, as somebody from Providence, even though my resume includes a lot of other stays.

Amy: Well, I'm wondering too, if you're moving around to all these places before you even choose your new domicile as Providence, that must have honed your exploring sensitivity.

Michael: Absolutely. Because so much adventure, so many stories, because whenever you get to go to someplace new, you're driven to discover what is there and sort of create new adventures. My primary friend, though, is the one that I met in first grade.

Amy: Tell me. This is a real friend or an imaginary friend?

Michael: A real friend. The critical friend. If you're curious right now about formative years, the name Sally is one of the most formative names you can apply to me. In first grade, we had just moved to Massachusetts. And this may sound shocking, but my parents just let me go door-to-door by myself to ring doorbells to look for a friend.

Amy: I mean we're talking about the 70s or the 80s?

Michael: This is like ’76.

Amy: Yeah, yeah, yeah, we were all latchkey kids, Gen Xers.

Michael: Right, no problem. Whenever I mentioned that to a recent parent, they're like, no, they did not let you roam freely through the neighborhood, knocking on strangers doors. [0.05.00] But sure enough, I knocked on what is going to become Sally's door. And I remember her mother answering the door and saying, “I'm looking for a new friend. I'm new to the neighborhood.” And her calling up to Sally, who I'm in first grade, she will be in third grade. And she comes down the stairs and we have a spontaneous play date together. And then we're inseparable for the next 15 years. (Laughs)

Amy: What a magical story.

Michael: Yeah.

Amy: I'm just looking at your life and you obviously have a confidence...knocking on a neighbor's door unattended would have been like harder for me. So not only do you have a confidence to go around and do that, but you hit the lottery, like the jackpot on one of those door knocks. That's exciting.

Michael: Absolutely. And she's two years older, has tons of older siblings. And she's an absolute badass.

Amy: Oh fun!

Michael: This is the person who really, like, inspires the dare. Like, can we climb the highest tree? Can we attach a rope three stories up in a tree and then attach bicycles to that and then pull it up into a tree, get on that bike and just swing out?

Amy: Oh my God. Swashbuckling. (Laughs)

Michael: That's a good term for it. She is that person and like uniquely weird. Recently my mother just moved out of that home. That home was in the family for 50 years. So I have been confronted with a bunch of the detritus of my youth.

Amy: Yes, that’s happened to me before. It's a weird thing.

Michael: Yeah. In my case though, there's an extra sparkle of weirdness to it because in this Secret Mall Apartment movie, there's this moment where it takes a segue into an underground sculpture installation, loosely just called ‘the tunnel.’ In that tunnel, in those shots, you'll see these sort of wooden coffin-like shapes hanging from the ceiling of that tunnel space. And there's about six or seven of them.

Amy: Yeah. It's very powerful.

Michael: What we don't know though, because there's no information about what that thing is, is that in those wooden coffins is every item I owned from the day I was born to my 29th birthday. It's my entire life in objects. And I mean that in the most literal way, every single object of mine that I could put my hands on. That is if you take into account, look into the rooms you're in and say, okay, well I own that coaster and that mug and that pair of jeans and you know, that, that… and you say, I'm going to document each one, put them in a plastic bag, put them in a wooden coffin, hang them and just leave them forever. That's it. I'm moving on from them. And in the late nineties, when I made that project, I had gone through that process. I went through my studio space where I lived. I went back to my parents' house and I cleared it out of everything. So I'd been living this entire time believing that...

Amy: So we're talking yearbooks and mixtapes and...

Michael: Everything. Literally everything. Every article, every pair of sock, every letter ever written to me, every stuffed toy from my childhood. Literal enough that the only thing I didn't put in there was my car, but all the CDs in my car, in the tunnel. The CD player, in the tunnel. I didn't put in my computer, and original negatives and some sketchbooks, but everything else that defines me as a human being went into that space. So in the last two months cleaning out this house, I have discovered that my parents, when I was out of the house, in my twenties, took the time to go into all the spaces I occupied in my old bedroom, place in the basement, put everything in plastic bins, labeled it, dragged it into the attic, put it in the furthest corner, and then just put stuff in front of it. I missed those objects when I did the tunnel project. (Laughs) So this is a...

Amy: So they undermined your concept… (Laughter)

Michael: I really thought I had like, truly, truly.

Amy: This isn't safe for Michael himself. (Laughs)

Michael: Yeah. So apparently it wasn't all of me. But it's also been a fascinating experience because I had [0.10.00] lost track of all those… large swaths of my history. So when I mentioned Sally, I've seen photographs of her for the first time from the seventies that I had moved on from. I'm seeing images and letters and objects that conjure up my childhood upbringing. And this is all happening in the last like two months. I mean, I'm having all these emotional experiences again.

Amy: What a psychological renaissance you're going through. (Laughter)

Michael: Yeah, big, currently, right, right now. And those objects are referred to as the objects that survived the tunnel.

Amy: Right. So I have to back up and ask why, why did you choose through the medium, through the methodology of art and art making, why did you choose to make such a drastic disconnection or, or a drastic line of demarcation?

Michael: It was a response…it was a couple of years in the making, but by the summer of 1999, I had a… I'll use the phrase loosely, ‘bad summer.’ So what that means is that leading up to that point, I had managed to accomplish in my social life and in my art life just a temporary moment of extreme balance, which means that I had an art partner for whom any art was possible. Like the two of us were destined to be an incredible arts duo. I also fell madly in love with somebody. And so my emotional spectrum, the yin and yang of my life, this desire to feel love at the deepest levels and also make the best art that was the most representative of myself as a thinker and a maker were all happening simultaneously. That balance is very hard to keep. And I didn't manage it as well as I could have. And by the summer of 1999, all parties were like, we are out. We are literally leaving the country. (Laughs) My art partners flew half way around the world, back to their hometowns. The love of my life took off to Europe. They stopped making my tape, so I couldn't do my art anymore. There was a brewing, the developers were coming. We could sort of start to feel that Fort Thunder was going to be targeted. So we started to see the first evictions. I always pictured it as like, if it was a country song, my pickup truck would just blow up and I would have died under the porch. Like it was just a bad summer. (Laughs) So I am in this emotional space of trying to understand like how do I move on when these big pillars of my life have left me? Very much through my mismanagement of everyone's emotions, and my own. And I had this moment of intense clarity where I was like, oh, this tunnel space that I had been managing for 10 years, I had a lock and chain on it, and I very much considered that my property, though its city property. (Laughter)

Amy: And this tunnel space was just like runoff drainage, right, for the city?

Michael: Yeah, exactly. It's a water drainage tunnel. It's 250 feet long, 20 feet wide, six feet high, it's a big structure underground. And it had a gate on the front that you could put a lock and chain on. And when I was 18, I put that lock and chain on it.

Amy: And claimed it!

Michael: I felt the passive permissions to install this moment of clarity, which was effectively, it's an act of self-portraiture that starts with some of the most simple questions. Who am I? What am I? And one of the answers to that question is you are the accumulative result of all the things you decide to keep around you. All the objects, everything you've bought, everything you've received, but haven't discarded or donated. All of the items in your space are a portraiture of you. And so that was an easy one to do. It's like, oh, that's easy. I'll just take everything I own and put it in this space, in these little coffins.

Amy: But it was more than just objects. It was also these castings.

Michael: Right, so the sculptures.

Amy: Yeah.

Michael: The sculptures are life-size plaster casts. The standing figures are life-size plaster casts of me. They are cast directly off my body in sort of the five tropes of me at the time. Anyone who knew me well would look at it and be like, oh, wow, that's just you.

Amy: Oh, that's tape art, Mike.

Michael: Right. There's depressed Mike, there's redemption Mike, there's joyous Mike. And then the other figures are more casts of friends and influences. And so it's sort of a sculpture garden of people who are myself and the people who have affected my life in the most passionate way. And then that space continues to just have layer after layer after layer of storytelling, about the losses of these great loves of my life. And so all the details about how the figures are positioned, or there's a figure in the front that's on a couch that's literally on their back in a hug, hugging a person who's just not there. And then if you were to cut that person open, the figure on the couch, there are organs inside of it. So there's all these details that no one's meant to ever see. Sometimes being super literal can be the best path. It's like, I want to leave myself down there. I will literally leave copies of my body in that space.

Amy: So literal in another way too, in a very geographically literal sense, this whole self-portrait is contained underground in a space that's only meant to be found by people [0.20.00] who are willing to put the effort in and the care in to finding it and not desecrating it or vandalizing it when they do.

Michael: Right. To extend on that, when I finished this project, I showed it officially to 13 people. And then I put a lock and chain on it, and I walked. What I have been informed over the years is that people discovered that there was a manhole cover at the very back of the tunnel, which was underneath train tracks. So on an active train track, there's a manhole cover between them that you could pull up and then you could sneak down into a series of short tunnels and enter into this underground sculpture installation with zero information about who made it or why it was there. So you got the sort of electric thrill of finding an underground civilization for you to explore and figure out. I have been told by the Sherpas of Providence, like the people who took the time to make it their mission to bring people there, many estimates have put that at over 10,000 people made that journey. And in that time, zero vandalism. So to your point, they were moved by it as a piece of artwork, I'm assuming. There's a sense of ownership because they made the effort to go.

Amy: And they discover it, yeah.

Michael: They are part of a larger story, and they actually got to experience a whole human being without knowing exactly what the narrative is. But all of me, literally all of me was down there to be discovered. And the demise of this project, the end of it, was a person who climbed down on the riverside, looked in, and they had the locked gate, so they can’t get in. They looked in and determined, in their wisdom, that there must be dead bodies in there, and they called the police. And they said, ‘There are dead bodies in this tunnel.” So on Fox News that night, here's a Fox News news anchor saying, basically, we're under the tunnel, or we're in the tunnels of Providence and who is the mad person who lives in these tunnels and makes these absurd sculptures? And there was footage of firefighters and police officers with flashlights just walking around being like, what is this? But they broadcast the location, they said, “At the corner of this and this.” They cut the lock. And I had made a commitment to myself to never curate the space. I could have easily just gone and relocked it. But I was like, nope, this is part of letting go. And sure enough, within a year, the non-adventure class, I'll call them that because they didn't make the journey through the tunnels at the back, got in there. And they're the first ones who were like, wait, what's inside these wooden boxes? And so they started getting tilted down. And they were fiberglass sealed. And someone finally broke the fiberglass, opened them up, and it's just a treasure trove of a lifetime of belongings. And so people started going through all of the stuff and taking the stuff. And so I got the wonderful humiliation of seeing what stuff you own is not cool enough to take. (Laughs)

Amy: Oh, god. Oh, god. Oh, I haven't thought about that.

Michael: Yeah. And it was fascinating. I was like, wow. So they took all of my underwear, all of my private letters, all of my... there's so many things that went way before the items that I thought were relatively... not expensive, but I thought they had some juice, but apparently not.

Amy: Like what? Your Walkman?

Michael: Walkman was gone, they took that right away, Walkman, CD player, CDs, also went. The last item standing, and I can still picture so clearly, all the cabinets are just completely bare, except for Herb Alpert & The Tijuana Brass on vinyl. (Laughter) [0:25:00] No one would touch it. They're like, not this.

Amy: So this tunnel art piece, ‘after the bad summer,’ lives in your life where? In terms of the founding of tape art as your mode of expression, and let's say, the creation of the Secret Mall Apartment?

Michael: So timeline-wise, tape art was invented in 1989, 10 years later, we end up with the tunnel within… that's in 1999. Two summers later, the World Trade Center is hit, and we have that disaster, and that starts the September 11th project, but simultaneously is the fight for Fort Thunder and the fight against the developers. That's happening simultaneously.

Amy: Yes. [0.30.00]

Michael: I do two years of the heavy lifting, city hall meetings, closed door meetings, trying to save the middle buildings in Eagle Square. We're working on the September 11th project, and then in 2003, we started the Secret Mall Apartment. So we're in a very emotional time period.

Amy: Very.

Michael: Yeah.

Amy: I was in Providence in ‘99, from ‘99 to ‘01, going to grad school at RISD. So we overlapped there. I did have the joy of experiencing Fort Thunder, though, on many a sweaty, raucous occasion.

Michael: Excellent.

Amy: And so I really felt, in the movie, but at the time as well, the fight to save it was something that reverberated around campus and was felt by the creative community. And so that was a moment. That was definitely a moment.

Michael: It was. Fort Thunder was the symbolic placeholder for all of the artists who are in live workspaces in these industrial mill buildings. Fort Thunder was the mythological center of it all. But to put that in perspective, Fort Thunder, and including three or four other mill buildings, with high estimates being 500, artists living and working within two or three city blocks of each other.

Amy: So generative. Can you imagine all that creative agency?

Michael: Unbelievable.

Amy: So the mill buildings themselves, because they're low rent, it means you're able to channel the resources, the limited resources you do have towards the generation and the generativity of making your work. So for anyone to call that underutilized, when it's actually like a percolating gold mine, is such a travesty.

Michael: Everything. It's everything. The pain of it reverberates to this day. And I realize we can't go back to a different economic setting, but it's worth emphasizing what you just said.I want to continue to articulate the thing you're saying there, which is that something I don't think people truly internalize is that artists have to get incredibly good at what they're doing on their own fucking time, on their own dime. And it's outrageous how good these artists get without being paid to get good at it. So by the time they're making art that's melting your mind, you're like this painting is so incredible, the song is so incredible, this dance is remarkable. The tens of thousands of hours of unpaid labor to get to that point is why having affordable spaces to live in is so critical because that affordability creates the space and time for them to get to that point.

Amy: Yes. Thank you for laying that out so concretely, yes.

Michael: I've had to articulate in Q&As after the Secret Mall Apartment movie, to many audiences who would say the phrase, we need more artists like you. We want more artwork like the art we're seeing in front of us here. We love it all. The tunnels, the malls, the September 11th memorials. Please continue to make your incredible work. And I have to remind them all of the majority of the work you're seeing here is all illegal. Patently illegal, like arrested illegal. And we have a conflict here because you really like that artwork, but you have to understand that all the artists that made it not only paid for it on their own dime, but also accepted all of the social risks and legal risks to make the work.

Amy: Right.

Michael: There's no system that exists for that type of artwork to be made, and there's no financial systems that exist to fund that type of artwork. So where are we? We want that work to happen. You're sitting here saying, I love it, we're barely surviving as artists, but we're making this work because we're deeply passionate and we have a lot of conviction about it as something that has to be made. And the only advice I can give anybody who's in an audience saying that is like, next time you're given any opportunity to vote for the arts, for the love of god, say yes to everything that has to do with funding the arts.

Amy: Thank you. Hallelujah. Amen.

Michael: Yeah. Even if there's a seed of you that's like, oh, well, I'm not really sure if I'm going to like the art. No, just vote, just say yes, because the ripple effect of funding for the arts always comes back for the betterment of society. Always.

Amy: I don't want to spoil the movie because I've already in the intro demanded that everybody stop right now and go watch it. But here we are with the Secret Mall Apartment now already behind you in terms of the actual creation of it and the originating narrative of it.

Michael: Indeed, indeed.

Amy: But the creation of the movie is a separate second chapter. And what fascinates me is that you and your collaborators who built the apartment, had the solidarity and intention [0.45.00] to safeguard and incubate the narrative for 17 years. Because there is the speaking of truth and then the hearing of truth, and sometimes those don't align time-wise. And so I think of this, that you had the presence of mind to document everything, which is a very artist mindset. I totally appreciate that, and it's just so scrappy and beautiful. Everything about it is like, okay, you think this is underutilized space and so you're going to erase this? Well, we think this is underutilized space and we are going to infiltrate, and this is our criteria for what underutilized space is and what needs to happen here. And at the same time, that whole work is now ready to be heard, digested, consumed. But it wasn't ready for that, because the audience wasn't ready for it.

Michael: True.

Amy: And so I think of it as this cicada of truth that has been underground, not dying and not dormant, but incubating until the... are you writing this down?

Michael: I did. I wrote it. It's a beautiful phrase. (Laughter) And you're really... wow, you're making some incredibly astute observations right now about our process and intent and how we held the story.

Amy: No.

Michael: Because we did not have to hold it. That is a very intentional decision. And you're one of the few people who understands that this story, when it broke in 2007, became international news. And it was in the moment of my arrest and the moments after that, when I internalized very quickly, I was like, oh boy, now we have to curate the narrative of this thing. And that curation of the narrative is going to be what is effectively the art project.

Amy: Yes. Yes.

Michael: It's in silence. It has no audience. There's no audience for this thing. No one's ever supposed to see it. No one's ever supposed to see the footage. It's not a public facing act or protest or performance piece. But now we have a narrative we have to control. And so here's how that went down. In short, one night in jail, a morning in front of a judge that went in my favor. I went home. I was home for two hours. I banged out a website in two hours. I bought a domain and banged out a website.

Amy: After a night in jail.

Michael: After a night in jail. Then I went to the children's hospital. I drew with cancer patients for several hours. And then I went to the Providence Journal, our local newspaper, at 4:30 in the afternoon, and I stood outside the building and I waited for journalists. And as they came out, I was like, are you a journalist? And I finally got someone who's like, yes. I was like, okay, here's the situation. You're about to get a police blotter, that's going to sound super sexy. Guy arrested at a mall apartment, blah, blah, blah. I'm begging you not to mess this up. Please spend the weekend with me, three days. I want Friday, Saturday, and Sunday with you, and we don't tell the story till Monday, because the only way this is going to get out is through you. And they said, that sounds good. And so for sure enough, for three days in a row, I every day met with these two journalists from the Providence Journal and we sat and we had conversations about it. How do we want to tell this story? What do we want to keep out of the narrative? And so on the following Monday, they did the AP release. And then Tuesday, they did more of a fully flesh localized story about it as a thing. And then on the following Wednesday, they did the Michael Townsend artist, who is he? Those three sort of opening volleys into this narrative set the stage for it to be a really excellent story that could be taken by anybody and transformed into the thing that they need. And that was what we wanted. We wanted this narrative.

Amy: You made sort of a modular building block system that the press could [0:50:00] build and carve up and use how they needed.

Michael: Yeah. Yeah, exactly, by building it three different ways.

Amy: But with enough control that they couldn't absolutely distort it or reinterpret it.

Michael: Exactly.

Amy: Brilliant! You’re a mastermind!

Michael: And then we made the decision and this happened in the first 48 hours or so. We're like, okay, if you look hard, you can find an initial interview where a guy caught us on the street talking and you see James and maybe Jay's face in one interview. And then we're like, never again. From now on, it's just me and Adriana.

Amy: So was that experience what made you realize you had to quickly wrangle this?

Michael: Well, that was part of it. We had we had controlled the written media part of it, but we hadn't had any conversations about news media stuff, cameras and faces. And we're like, okay, from now on, until for at least the next couple months, when possible, I am in a buttoned-down shirt. And when possible, we have Adriana also and we are a couple just trying to live the American dream. And we want people to look at us and be like, oh, these two, I support these two. Look at them. Look, she's so pretty. He's giving it his best shot. (Laughter) They're just trying to live some sort of dream. I don't think I completely understand it, but we should give these guys the benefit of the doubt, at least. And sure enough, we had lots of interviews where it's just the two of us just talking as if we had just moved in there and just trying to get our slice of Americana. And then this story just went off the beautiful rails, which means that so many news outlets, from every spectrum of the political climate reached out to be part of the storytelling. I sat on the couch with Fox & Friends. I, the day later, would have a one-hour NPR interview, followed the next day by a full page in the National Enquirer, followed the next day by doing back-to-back interviews with conservative radio stations in the Midwest for six hours in a row, where they are super excited because a lot of radio stations are excited to try to… what do you say, humiliate a hippie. Nothing brings them more joy (laughs) than… as we've used in today's language would be “to own a lib.”

And so looking it’s like, oh, well, what do we got out here? We got some floppy Rhode Island liberal artists. We're going to ruin this guy. Nope, they are not going to ruin this guy, because I am very interested in trying to sort of make this narrative as universal as possible. And I brought them into the fold very quickly about how this story actually affects them also. And so we're able to turn the tables really fast. I think this is one of the reasons the story did well is because it spoke to so many different types of audiences and we had controlled it so carefully. Simultaneously, a writer's strike is about to happen in Hollywood. This story has national and international momentum. So there are writers in Hollywood, executives in Hollywood who are like, oof, we got to get these guys. Movie deals, book deals, TV deals. I am not exaggerating when I say we got 10 to 14 calls a day from Southern California looking for some sort of deal where they could take it and turn it into a product. We just need to turn it into something, a product that people will pay money to go see.

And we made the decision, no, we're turning it all down. Any deal coming our way, no matter how juicy it is, no matter how much money is put in front of us, even if someone's like, we'll give you a quarter million for your life rights. No, we're turning it down. Because as a piece of narrative art, we had done our best to control it and it was doing well. And we thought it was really critical that our faces, our ideas, our politics, our history were not the tip of the spear. That the story itself was the critical thing. And we kept seeing emails from people saying, with the theme, the main theme was always thank you. Thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you, thank you. Because they saw in the story themselves their love of tree forts, their love of malls, their love of sticking it to the man, their love of friendship and discovering weird spaces. [0.55.00]

Amy: But I’ve got to ask you, at a time when, so this is 2007, we're also headed into the financial crash. At a time when austerity is staring you in the face, how easy was it to make that sort of unilateral decision to say no to all of that when one of those deals probably could have financed all your art for a while?

Michael: I know it always sounds like lunacy to anybody when you turn down money. That said, I have made a career out of saying no to people in tape art all the time. So we get offers… we embrace the temporary model of tape art. We also embrace the free model of tape art. We are making tape art synonymous with public art and community art. At its heart, it's designed to be from the people for the people. And anytime you make any offer to make art a prisoner was always turned down, regardless of how much money it was. We just got comfortable with saying no to people. I remember the first time I was offered money to do commercial tape artwork, 1995, Bentonville, Arkansas, drawing. I was actually drawing on a Walmart. Walmart’s are the best community art walls. It's an entirely different conversation, but drawing on this Walmart, and they were shooting a Pepsi commercial near us. And the Pepsi commercial people were so enamored with the drawing, they came over and they had a check in their hand. They're like, hey, we have a check here for $4,000, we just want to be able to shoot in front of your mural. And we're giving this to you so we can have the rights to publish and print it. And my taper partner and I looked at it and we're like, no. And it would have been life-changing money for us at that time, $4,000 when you're 24 years old, you're like, (gasps) (laughter), the things we can do with this.

Amy: Yes!

Michael: But that was the first time that we just sucked it up. At that time our budget for food was $15 a day on the road. So that helps put in perspective what $4,000 looks like to us. And we're like, well, this is the beginning of us being moralistic jackasses about our work. And so you do that for long enough, you get really good at being like, here are my boundaries about how I want this story to be told and being very strict about it, which got us ultimately a product that I feel very good about, which is the Secret Mall Apartment, right now in 2026. We just spent nine days on the top 10 on Netflix.

Amy: I know. Congratulations!

Michael: Outrageous! We have no business, zero business being on that list.

Amy: What are you talking about? You have every business the same way a dandelion has business growing up through a crack in the fucking sidewalk and saying, I'm here and I've been here all the fucking time and I'm here to remind you. (Laughter)

Michael: Surprise!

Amy: Just because we go underground doesn't mean we won't pop back up somewhere else.

Michael: All right, fair enough, fair enough. (Laughter)

Amy: Back to the narrative and the incubation for 17 years. Part of this intentionality was how you wrangled the narrative when it came out initially, and then how you kept it safe until it was ready to emerge again. Why now? Why is it resonating so hard right now?

Michael: The movie's crushing it because of good word of mouth, is my guess. But I think people are recommending it to each other because it illustrates a group of people up against emotional and contextual circumstances to which there are no solutions, and using whatever means they've got, which for us was the arts, to try to navigate it, objectify it, come to peace with it. [1.05.00] I think right now there is communally a lot of discontent from kind of everybody, about the sense that we're not getting what we want. Everyone's mad that things are terrible, and they're never going to change. And so, they feel like there's got to be some sort of solutions or pathways through, and the movie does a good job of illustrating that you can still actively solve issues, at least, even if it's just for your own mental wellbeing.

Amy: I also think that what the movie demonstrates is the raw power of creative agency. And when it is harnessed, and you sort of combine it with your own scrappiness and resilience and ingenuity, it can be very tactical, very precise, and it can be aimed at the cracks in the system that then it becomes a wedge. And it can expose hypocrisy, but it can also in the form of your tape art 9/11 monuments… and Colin Bliss says this so beautifully, he describes your team as an elite strike force of empathetic artists. And he sort of chuckles as he's saying this, because those seem like polar opposites, but they're not.

Michael: They're not.

Amy: They are not. It's such a quotable moment, because those are not opposites. Those are very much, when you put… it's just the intention is different than most people think. But the movie itself, I think, demonstrates this kind of willingness to marshal your creative agency and to target things that are of value and important to you, even if they're not about putting a megaphone up. But understanding that sometimes the power of reaching the target happens almost subliminally.

Michael: It can be very quiet.

Amy: It can be very quiet. And it can be gotten to in stealth mode.

Michael: Yes. This movie illustrates that type of approach very, very well. People are really moved to just see a group of artists and friends working well together. I've had so many people in their 20s, artists in their 20s walk up and ask directly, how do I find my people? How do I find my friends? How do I get this? And there's also a nostalgia from 20 and 30 year olds about this idea that there was a time where you could keep secrets or you could do things without being monitored or surveilled. My arrest… the project ends a couple of months after the iPhone is announced. So it gives you a sense of where we are on the technological timeline. And so the little digital camera that's used to record the footage of our process is not recording and being sent into the cloud. It's not recording and being shared or transmitted to social media. There's no expectation it's going to go anywhere. And so the footage, when you watch it, has the air of voyeurism to it because no one's performing for the camera. The editor of the movie flat out told me, [1.15.00] he's like, yeah, I watched all of your footage and no one ever looks at the camera, not even once. I was like, oh, that's very interesting. That's an experience that feels more distant now than it ever has. I think especially younger people, when a camera comes out, there's an assumption it's going to be broadcast. I think in the movie there's sort of like this inkling of, and ‘nostalgia’ is the word I keep coming back for, about a time period when those feelings didn't exist.

Amy: Right.

Michael: When you're with someone, you are with someone, like you are with them. No one's on their phones, they're just present with each other, coming up with plans, executing their plans.

Amy: Your presence with each other is also very palpable in the movie, in the documentation.

Michael: Yeah.

Amy: I also felt for me, there was a fondness of my art school years when there is that kind of, you find your tribe and then you find your collaborators and you pull these off these enormous feats together. And it's this symphony of moving parts that also frequently comes with a lot of like deep emotional bonding and vulnerability and fueled by whatever you're into at the time.

Michael: Which builds trust.

Amy: Yes.

Michael: Everything you're saying there is about building the bond of trust. And I think without that word ever being used, that's what people are seeing in the movie. They look at all these people, like, these people trust each other a lot.

Amy: Yes. That's what is the unsaid word that is powering every single interaction in that.

Michael: In the movie, yeah.

Amy: And people are recognizing that. And they're recognizing it because it's calling attention to the absence of it in their own social dynamics.

Michael: Yes. Yeah.

Amy: That's powerful, that's really powerful, I'm feeling it in my body, which is why I just had a big outburst. I want to talk to you about how this is hitting you personally, because you have a comfort level of operating in the shadows and skulking around in the tunnels underground. (Laughter)

Michael: I’m listening. (Laughs)

Amy: But you also have had these moments of being extremely visible in which you wrangled them with a lot of intention. And it's weird to be sort of out there for parasocial consumption. How's it hitting you, of being a movie star?

Michael: As a public artist, I have spent a lot of time being strikingly transparent. I stand in front of walls. I make drawings. Sometimes those drawings are not good, and then I fix them and I make them good. But I have to go through the entire process of the light humiliation of making work in the public and talking to people in real time, getting their feedback and their observations, including them. [1.20.00] So that's a very public life. Countering that is this urge to make works that are unseen. The tunnel projects, Secret Mall Apartment, I have some film projects. There's a bunch of stuff, still unseen, that I have in my life. The dichotomy in my brain, the best way I can describe this is, if you can visualize a stadium show where there's 20,000 people in the audience and they're five minutes behind schedule, if I was backstage and you ran up to me with a mic and you're like, ‘Townsend, you got to get out there and you got to keep these people busy for five minutes.’ I'd be like, no problem. I'd go out there and I could wing it for five minutes in front of 20,000 people and I would feel nothing. Zero fear. I'd be like, I got this. I don't even know what that thing's going to be. But I do know that as soon as I step out there, my brain will flood with… I'll read the crowd and be like, oh, is this about telling stories? This is about making jokes. This is about singing songs. I'll figure it out. But the second I step backstage, if you walk up to me with a phone and you're like, hey, we've got this dope video of you doing that sing along with the whole crowd, I'm going to need you to post this online to Instagram. I would fucking fall apart.

Amy: Yeah, no, I relate.

Michael: Can't do it. (Laughs) It would feel like there's a disconnect there that is cavernous for me. And one of the big things that happened in the last year is my art partner and I, Leah Smith, have finally committed to using Instagram. This may not sound like a big deal, but for us, and I am not exaggerating when I say to you, it took me three years to psych myself up to post. Outrageous. To literally be like, okay, I'm going to push the send button. Okay, no, wait, maybe one more year. I need one more year to psych myself up! So we started using Instagram and my art partner, Leah and I have been committed. We're like, if we're going to do it, let's do it right. We'll make what we perceive to be as good content. We're not looking at trends. We're not looking at anything like that. We're like, let's just make authentic content that's very clearly us being ourselves as much as we can when we're in front of a camera. (Laughs) And so I want it to be effectively like an extension of the film, where you see someone on film who from that time period, filming myself in that sort of that style, and then continue to have that journey where you feel like you have access to that person because they're being authentic about what's going on in their lives.

Amy: I mean, you could continue it in the same way that you did with those, were they Optia optics cameras, (laughter) you could just mount a few in your studio and every now and then just look back at the footage and be like, oh, this is a pretty good cinema verité moment. We'll post that. What feels important to you right now. And how do you think maybe now that this story about the mall, but also this additional attention on tape art might be constructive to you personally in your own personal evolution, but also to your art practice and how your message and your movement might move forward.

Michael: My art life is sort of kind of keenly cut in half between big art projects that run the gamut from like esoteric stuff that no one will ever see to these big public art projects. But the other half is really rooted in art education. As a community artist, I am forever deeply, deeply interested in how people think about art, make art, think what their relationship to art is or could be. We calculated that I have worked with over 60,000 first time tape artists in all the workshops that I've done.

Amy: That is scale!

Michael: I'm in my fifties now. I can't get to everybody. (Laughter) It's exhausting. Through the movie and through the lens of art education. This movie is doing all the heavy lifting right now.

Amy: Isn't that beautiful? [1.30.00]

Michael: How wonderful is it that there is this document that shows a wide buffet of art ideas, and from the side of the spectrum where you're like, that's not art, I would never call that art. And then it sort of moves to the middle space where you're like, oh, that's definitely, I know that that sculpture, that's drawing, I get it, that's art. But then it moves into sort of a social space where it's like, oh, it's art as process or art and healing, I guess it is. And I think between all of those different art lenses, I think it gives people an opportunity to reevaluate what their definition of art is. And in the movie near the end, there's this wonderful supercut of five or six voices answering the question, is this art? And it starts with someone from the Met, a curator from the Met. So, you know, top of the pyramid, indicating, gesturing in the direction of yes, indeed, this is art. And as the voices get closer to me as a person, what's beautiful is that by the time it gets to my girlfriend and my brother, both those people are like, I don't know. (Laughter)

Amy: It doesn't make sense to me.

Michael: Is it art? I'm not entirely sure. (Laughter) And I have found, really, I was so deeply moved the first time I saw it and being in audiences and watching them, I was like, this is one of the most important parts of the whole movie, because it provides a voice for people who are, you know, at the beginning of their art journey or art appreciation journey, where the people closest to me are saying aloud the thing that they may be afraid to say. And I think it's so, so powerful. And so my hope as an art educator is that this film will continue to sort of bounce around Netflix and be shared and continue to be a good part of the conversation for the years to come. In our own personal life, I have not said this aloud in any interview… do you want me to say it aloud?

Amy: Give it, give it!

Michael: There is an assumption, because we are on the Netflix and we were somewhere between a James Bond movie and another James Bond movie and some other multi-million dollar thing, that we receive cardboard boxes from Netflix every day full of cash. That somehow this movie and its incredible success has somehow been a windfall for us.

Amy: That's not how it works.

Michael: Not how it works.

Amy: You have to build the channels. You have to have the buckets to catch the money.

Michael: You’ve got to have the buckets, exactly. And this is not because we are bad business people. This is not because we said no to opportunities, it's nothing like that. And we're not going to get into the weeds about licensing and who got what from what.

Amy: Yeah.

Michael: But I can share with you that effectively we make no money from this movie. That it is, as the subject of a documentary, it is not normal, unless you're Melania, to receive money for your participation. And you could argue in your mind all day about like, oh, well, you should have charged for this, you should have asked for that. The movie is made by an independent filmmaker who is also another artist struggling to survive in a system.

Amy: Exactly.

Michael: So there's a totem pole of artists and industry people of which we are at the absolute bottom. I'm not saying that as a complaint, that it's not a negative thing.

Amy: The producers who financed it, they need to recoup. And then, yeah, so...

Michael: Exactly. Everyone is in a ditch when an object like this is made. And to recoup, to actually reach a point where you are even just whole, is a whole journey in itself. We're in the position of just trying to champion the film in the hopes that it will make the directors and the producers and the people who made it happen, even making them whole, if we can accomplish that, that's a victory. That would be huge.

Amy: And a victory for the artwork that is the movie. Yeah.

Michael: Yes, absolutely, as a piece of art, as a piece of documentary film, because it's an excellent, excellent piece of film. And we want it to continue to get attention and be shared and affect people. [1.35.00] In our world, we are left to try to capitalize, for lack of a better word, on the attention that it gets. But that is done unguided. We just went from just two artists sitting in our studio in Providence, just trying to work on our next art project to accidentally becoming famous enough that I can walk around in another city and people are like, oh, wait, you're from Netflix. I saw you. So we're like semi-famous right now, but what does that mean? It doesn't mean you get a paycheck. So it's not that.

Amy: No. Does it fall within your value system to receive donations from individual people who would just want to support what you're doing?

Michael: Hundred percent. So we, in the first couple of days, the movie was up on Netflix, received a lot of messages. So many, it's endless. Every day we have a couple hundred good wishes. But within that are people who say, I need support to you. They can read the tea leaves. They're like, you need money…So on our website, we did put up a link for donations. And within an hour of it going up, we saw just really… we're so deeply moved because we had never received a donation ever in 35 years of doing community work and volunteer work, to have the generosity of a stranger somewhere in the United States be like, here's some thank you. Here's some help. So in the tape art scenario, we are definitely interested in those being experiences where the person doesn't… they're strictly non-commercial.

Amy: And they don't feel like they need to, that they don’t feel that pull.

Michael: There's no pressure. There's no anything. But the movie is a different thing, this is a different creature.

Amy: It's a different creature, but if the people who are touched by the movie want to help the tape art artist keep touching other people, and this is the true spirit of community, if I'm over here, and I can't physically touch the people that you're going to touch, but my dollar can help you do that, and I can be part of that community, then I want to be part of that.

Michael: You can be part of it. And we have a relentless track record of working in psychiatric facilities and schools and hospitals. So any dime coming our way, you know we'll be invested in the materials and help subsidize our work in those spaces, which runs the gamut from volunteer to just small stipends. Tape art and our expertise in working in those institutions is so niche. Like our work working with teens in psychiatric wards, is it bragging? It's sort of bragging. We're so good at it. My goodness. The impact of the tape art experience in those spaces, with those patients that have been pulled from society and are just trying to right their ships, to give them opportunities to draw on the walls of the institutions where they're frustrated to be in, to express themselves in front of their peers and the staff, and to sort of navigate all the socialness of it all. The need to ask for help, the need to create content that maybe pushes the boundaries of what they're allowed to express in those spaces. And our job is to sort of help them feel satiated without pissing everybody off. (Laughter) And the medium of tape art allows us to do that work. I guess I'm illustrating all that to say that any donation that comes our way just fuels all of these types of works.

Amy: Yes. And I'm also conscious of, and I'm not sure how prevalent guerrilla art still is in your practice, [1.40.00] but I'm conscious that there is no formal mechanism for funding that. No corporation can legally give you money to go do something that's illegal.

Michael: That is true.

Amy: But the people can.

Michael: They sure can.

Amy: The people can donate, No Strings Attached, and if there's the promise of some of these beautiful works of emotional resonance, care, and resistance conducted with strategy and precision…

Michael: That is who we are. Any money that comes our way goes into that system.

Amy: Yes.

Michael: Yes. And does that mean you'll know what's happening with it? No. Are you rest assured it's going into the things that are parallel to the things you saw? 1000% yes.

Amy: Beautiful. It is my pleasure to hopefully be a conduit. I hope anyone who's listening hears that message. And before we sign off, I mean, is there anything we didn't cover? You talked about trust being so apparent and resonating in the film. I hope that we've established some trust here. And I hope that you feel safe with the caretaking of your narrative.

Michael: I do. Indeed. I found myself just openly sharing with you an occasional tidbit of stuff that I haven't been very public about. So thank you for creating that environment.

Amy: Hey, thanks so much for listening. For a transcript of this episode, and more about Michael including links, and images - head to our website - cleverpodcast.com. While you’re there, sign-up for our free substack newsletter - which includes news, announcements and a bonus q&a from our guests. We love to hear from you on LinkedIn and Instagram- you can find us @cleverpodcast and you can find me @amydevers. If you like Clever, there are a number of ways you can support us: - share Clever with your friends, leave us a 5 star rating, or a kind review, support our sponsors, and hit the follow or subscribe button in your podcast app so that our new episodes will turn up in your feed. Clever is hosted & produced by me, Amy Devers with editing by Mark Zurawinski, production assistance from Ilana Nevins and Anouchka Stephan and music by El Ten Eleven.

Michael and his Tape Art partner, Leah Smith, at Katja.

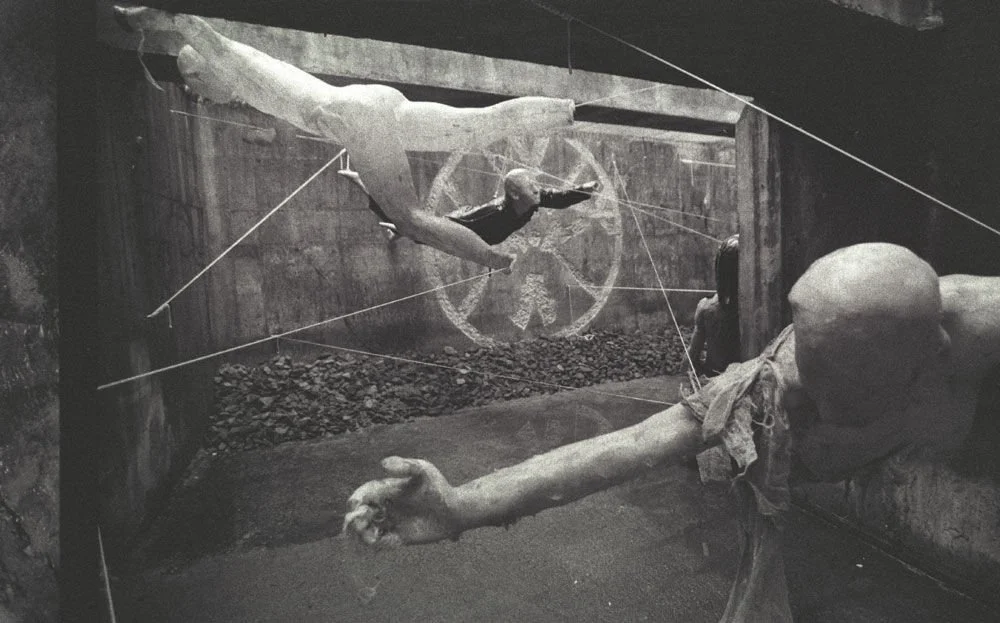

The Tunnel, 1999

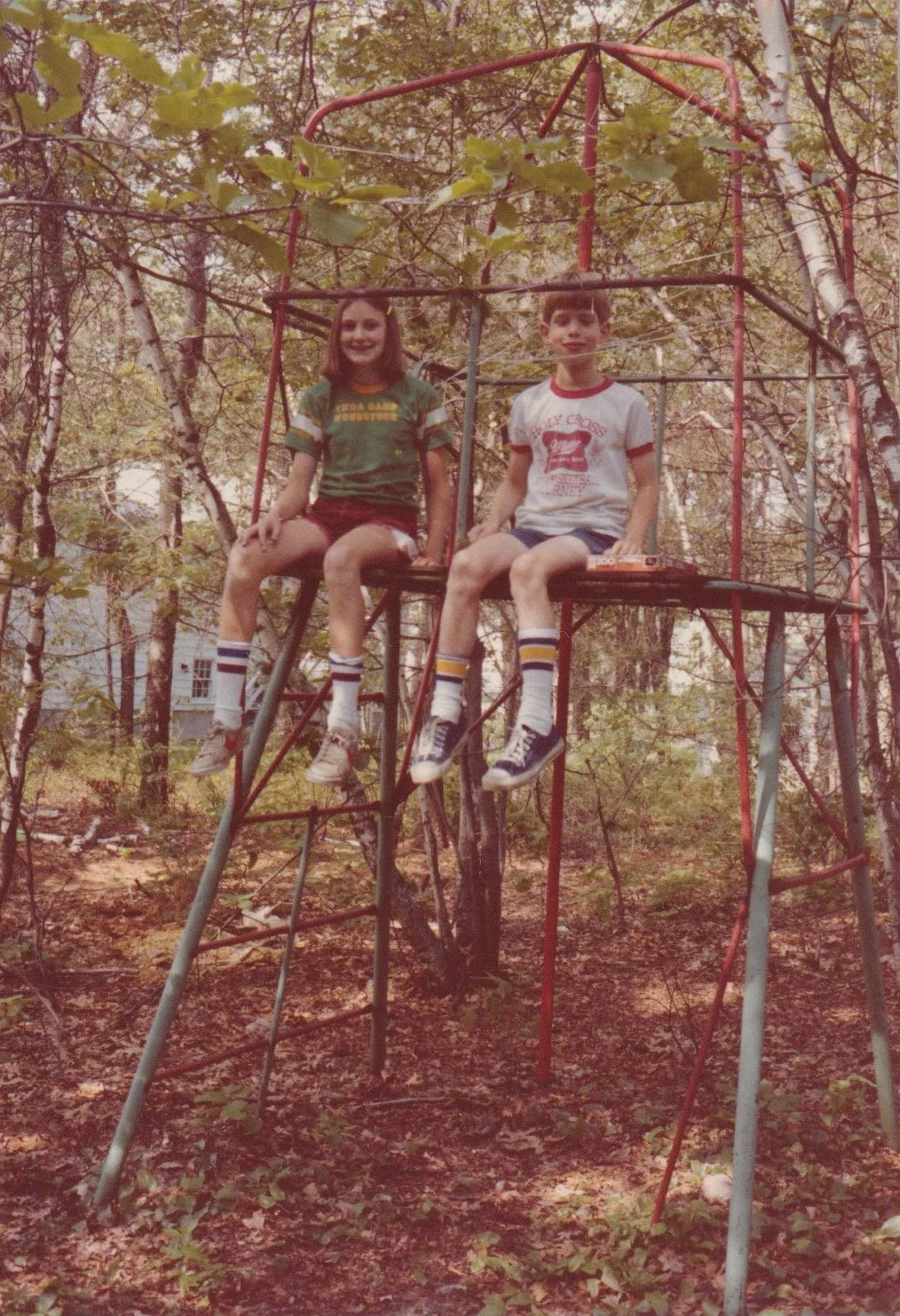

Young Michael and his friend, Sally.

The Tunnel, 1999

Hygia, 1998. Credit: Tape Art

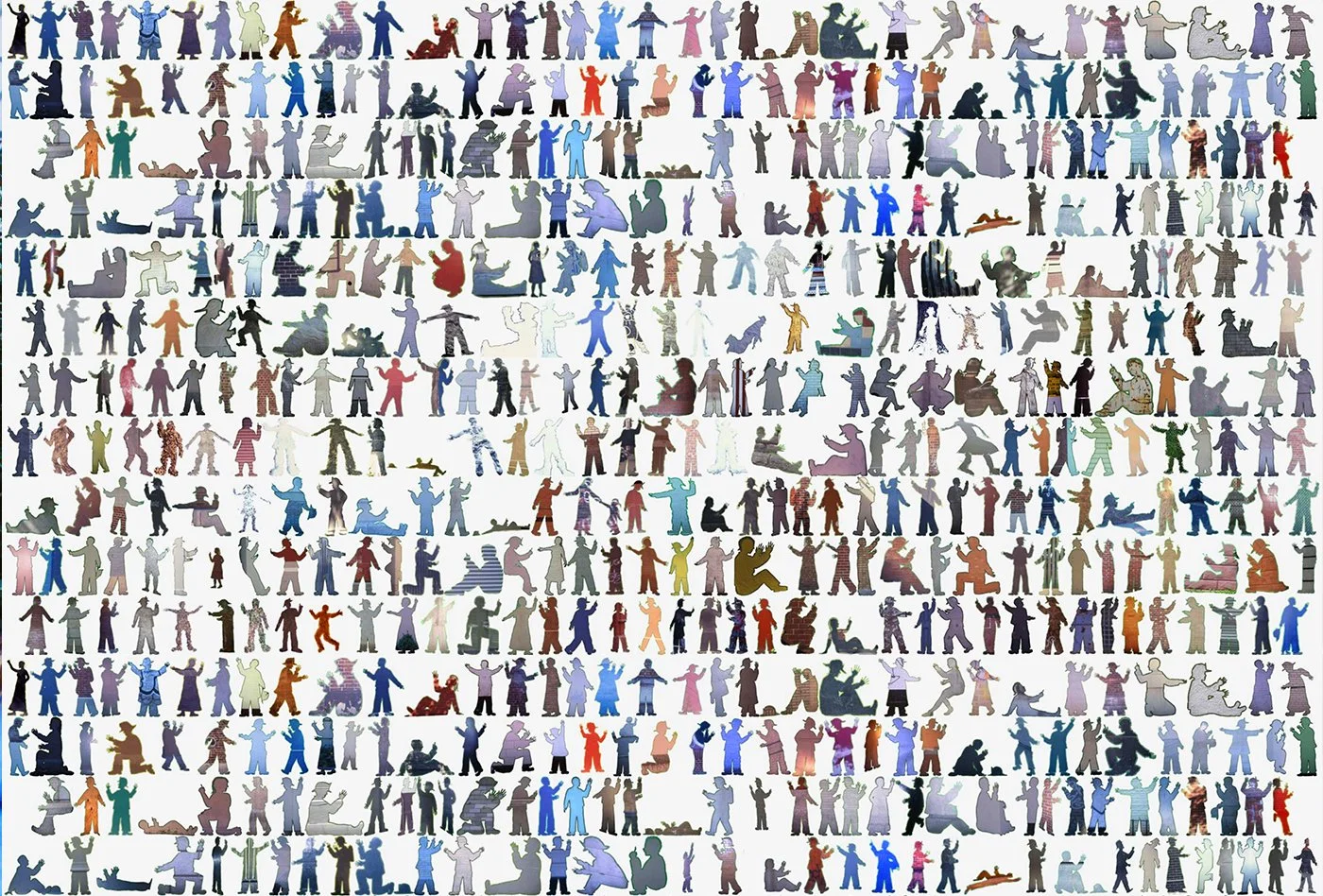

NYC Project, 2001 - 2006. Credit: Tape Art

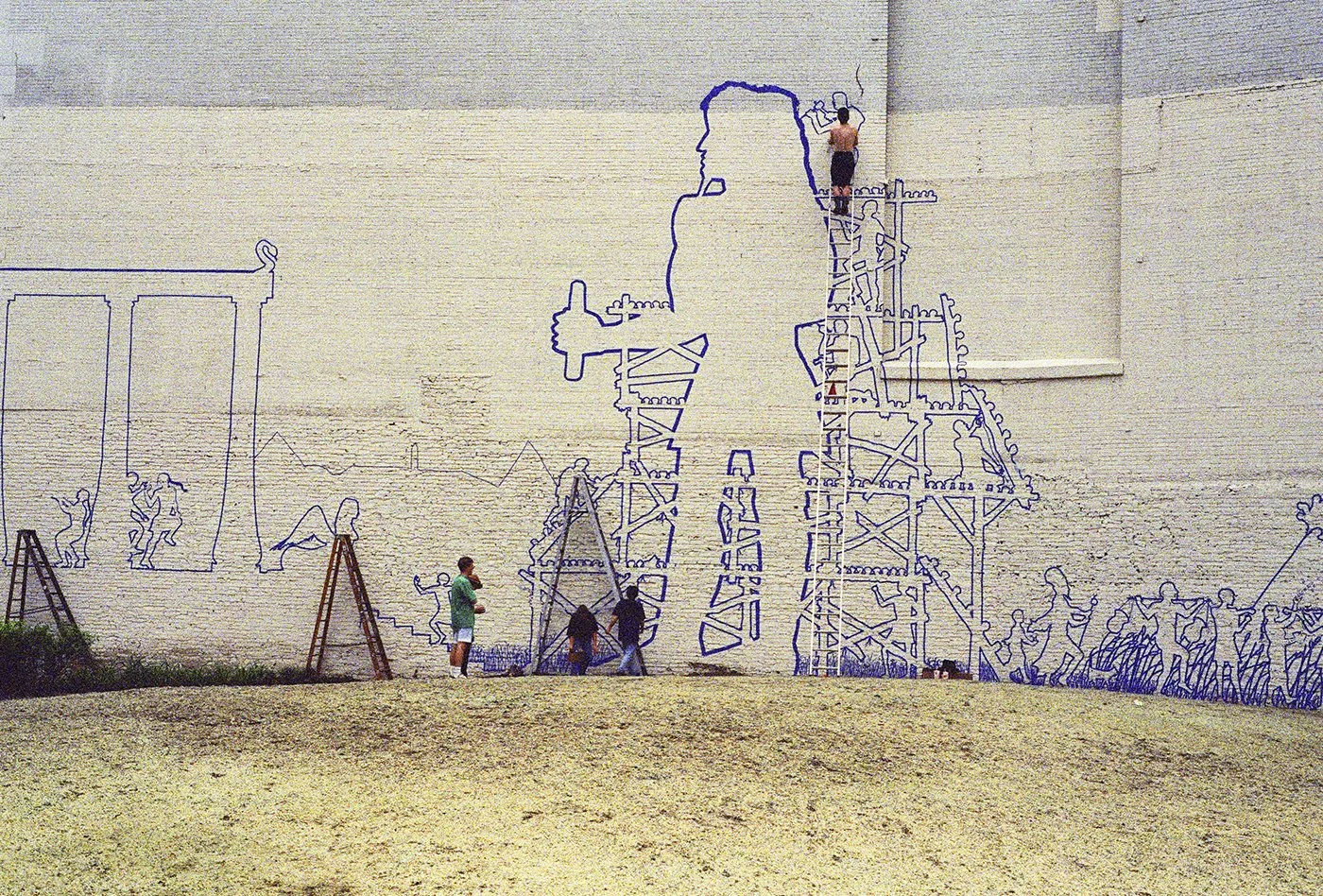

Egypt, 1992. Credit: Tape Art

Womens Tree, 2017. Credit: Tape Art

Clever is produced and hosted by Amy Devers with editing by Mark Zurawinski, production assistance from Ilana Nevins and Anouchka Stephan, and music by El Ten Eleven.